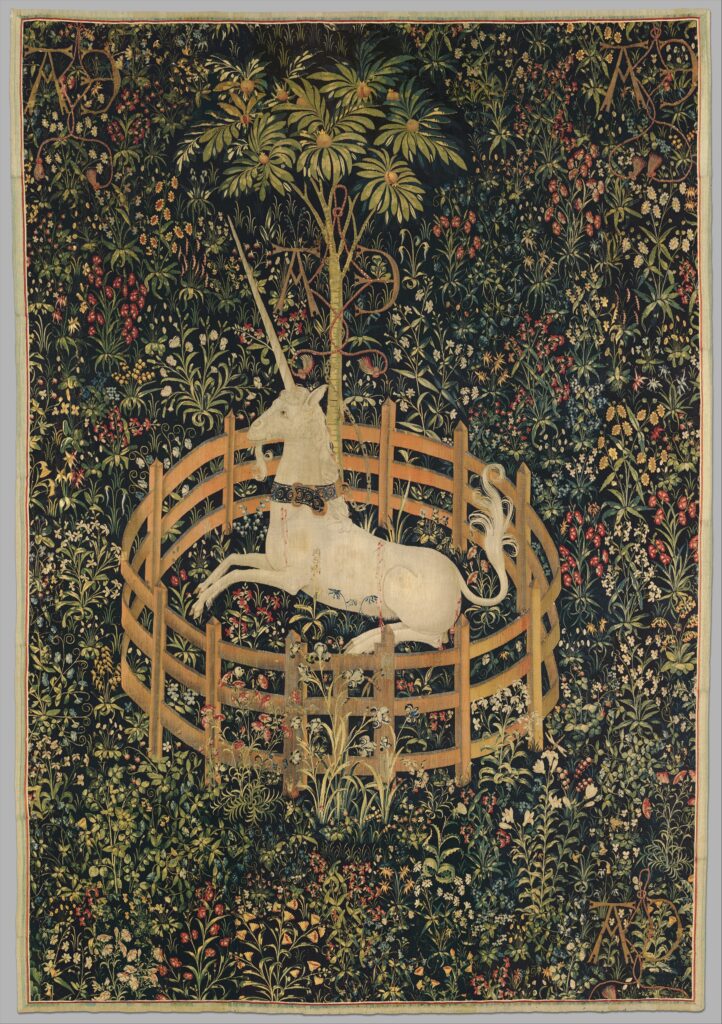

A unicorn rests in a garden, held captive in a ramshackle wooden corral. The magnificent creature wears an intricately decorated collar, a delicate golden chain keeping it tethered to the spindly pomegranate tree in the center of the corral. A kaleidoscope of flowers surrounds the beast, accentuating its ethereal beauty. Strangely, the unicorn seems at peace despite being confined to such a small enclosure.

The scene described above will be pretty familiar for art history, museum, fantasy, and pop culture enthusiasts alike. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s The Unicorn Rests in a Garden is perhaps one of the most iconic pieces in the museum’s impressive collection, cementing itself as a cultural touchstone of the Western European medieval zeitgeist. And, yet, despite its impressive reputation, little is known about the tapestry or its six (potential) siblings from the aptly named ‘Unicorn Tapestry’ series.

Though beloved among medievalists and Renaissance specialists, tapestries are surprisingly unpopular in the art market. Few have survived to present day and those that have are considered priceless historical artifacts, rather than high-value collector’s items. Rarely has a tapestry from the 1400s-1600s surfaced in the art market and a lack of extensive scholarship means there are less “eyes” keeping tabs on them. They are, theoretically, the ideal subjects for someone with a penchant for nefarious activity in the art market.

Despite this, there have been few cases involving tapestries in the world of art crime. Thus, I propose, for the sake of protecting both art enthusiasts and GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) institutions across the globe, a step-by-step guide on forging your very own medieval tapestry, stitch by stitch. You know…for science.

❧ Step 1: Learn Your Medium

What is a medieval tapestry, or a tapestry for that matter?

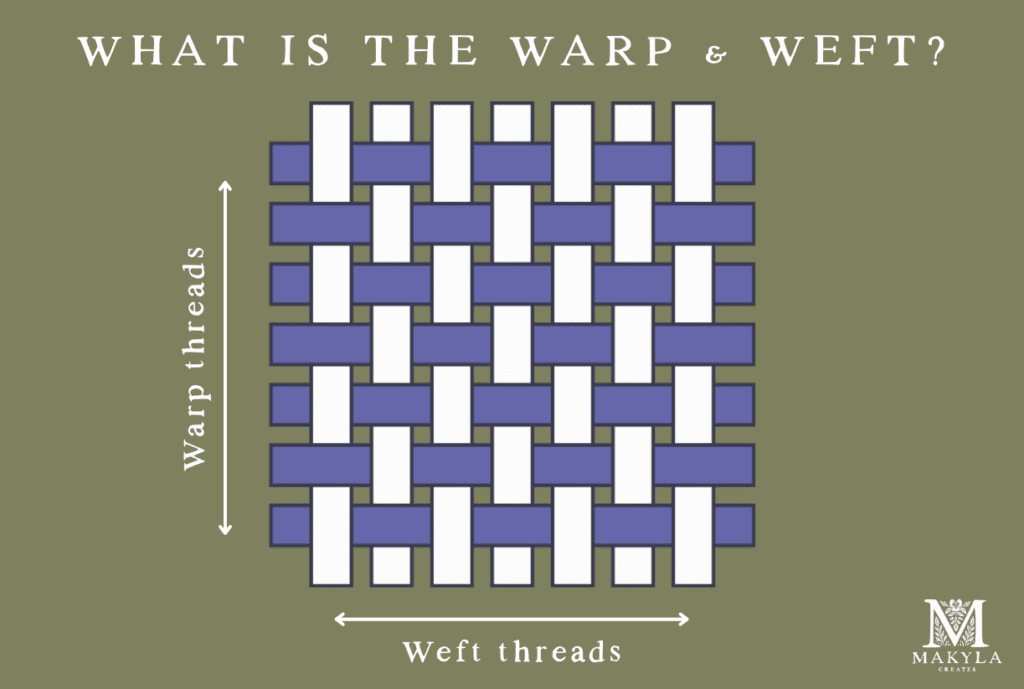

Tapestries fall under the textile category, consisting of thick strands of fabric woven together in colored weft threads or embroidered on a canvas. To be specific, tapestries are weft-faced plain weaves that use repeated, discontinuous wefts used to conceal any warps. Visually, they are characterized by the elaborate designs, sometimes in the form of highly-detailed pictures or floral, mandala-esque patterns.

Tapestry weaving is one of the most splendorous crafts, due to the extensive care and effort it takes to produce them. This means tapestries are also fairly expensive, falling into the category of luxury goods. Between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, they were commonly used to decorate the residences of the wealthy elite and even public spaces. Tapestries bear an astonishing likeness to other mediums, such as canvas paintings, wall murals, and printed fabrics, making them difficult to identify.

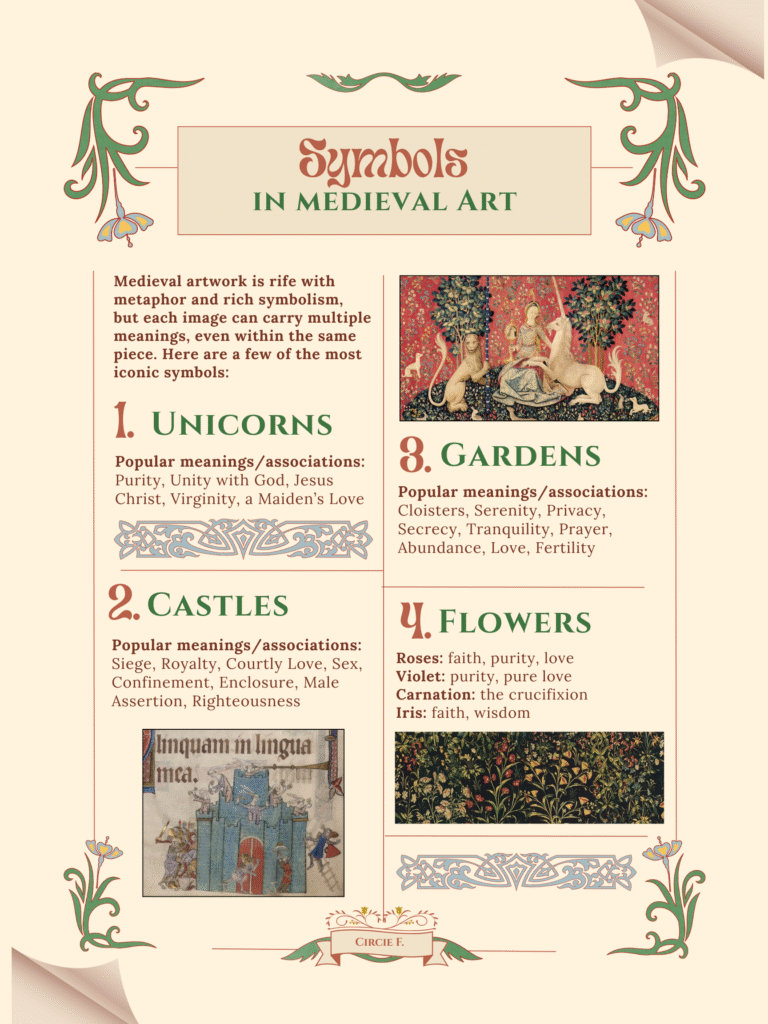

Explore the common symbols in medieval art with the infographic below:

Tapestries in Pop Culture

Not convinced you’ve seen a tapestry before? Take a look at these examples from popular media!

The opening credits to The Last Unicorn (1982) features a creative rendition of the ‘Unicorn Tapestries’ series, delicately blending medieval iconography with early 1980s animation.

During a scene in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001), the Lady and the Unicorn tapestry series is featured as decorative wallpaper in the Gryffindor common room.

In Shrek the Third (2007), a portion of the Bayeux Tapestry can be spotted decorating the walls of the Worcestershire Academy auditorium.

❧ Step 2: Learn Your Craft

As we’ve discussed, the process of tapestry weaving is incredibly meticulous and time-intensive, having changed little over time. European tapestry weaving involves a loom with two rollers which stretch the plain warp “load-bearing” threads. France, Germany, and what is now Belgium were major production hubs for medieval tapestry weaving, and typically employed wool warps, but linen may have also been used. A weaver would work in reverse, weaving from the underside of the tapestry in a back-and-forth motion that drags a weft over a warp and then below another, alternating until the design is completed.

Warps and wefts are the two essential parts of weaving, particularly in the production of cloth. Warps typically remain vertical as wefts are woven horizontally through their companion warp.

Tapestry-weaving is essentially a tactile manifestation of simple math. Framed on their looms during production, tapestries resemble grids of alternating threads–the warps and wefts. Once the wefts have been threaded through each warp, the weaver “squishes” them down to obscure the warps. The warps act as the foundation of the tapestry, maintaining the work’s architectural integrity. Warps are the skeleton upholding the weft’s decorative flesh, much like how Gothic cathedrals served as the osseous frames for the glittering, jewel-esque stained glass panels.

The following video demonstrates how modern tapestries are made:

In medieval and Renaissance tapestry production, the final design of a piece was modeled after a specifically-chosen cartoon, or full-scale colored pattern. To copy the design as closely as possible, a weaver would trace the cartoon’s patterns onto the pre-installed warps. The cartoon could be hung behind the weaver if using a high-warp loom, or folded and cut into strips to be placed behind the warps if using a low-warp loom. More complex designs required a low-warp loom, as their patterns could be directly copied from the sectioned cartoon strips placed behind the warp threads, though this technique requires the cartoon’s design to be reversed since the weaver works from the back of the tapestry. Most medieval and Renaissance tapestries were produced using the low-warp looms, since they were more efficient in reproducing highly-detailed designs.

Tapestry quality was also highly dependent on four major factors:

- The reference cartoon

- The weaver’s skill at translating the cartoon’s design into woven fabric

- The number of warps used per centimeter and the “grade of the wefts”

- The materials used

Cost, of course, was also a major factor. Because their creation involved highly-intense labor, large tapestries would require more weavers, particularly experienced ones, further raising the cost of their production. Generally speaking, a team of weavers might produce about one square yard of a tapestry per month, with more elaborate tapestries taking far longer to produce even half a square yard.

❧ Step 3: Do Your Due Diligence

To successfully commit a forgery, one must be an expert not only in the medium of their duplicitous object, but also in the general provenance trends of authentic works. Therefore, our own forgery process should include a hefty amount of research into famous examples of medieval and Renaissance tapestries, as well as their biographies of ownership.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s The Unicorn Rests in a Garden is one of the most famous tapestries in the world. Thought to be from a seven-part series of similarly-themed tapestries, the work illustrates a portion of a cohesive storyline centered around the titular figure of the unicorn. Despite its notoriety, its creator has remained unknown all these years, a detail that becomes quite relevant if one were to forge a tapestry in its likeness. We do know that the cartoon is likely French, while the actual tapestry itself is from the Southern region of the Netherlands.

The wool warps were combined with wool, silk, silver, and gilt wefts to craft the image of the elegant creature, which is likely an allegory for Jesus Christ or, at the very least, is a symbol of fertility. Unicorns, along with other mythical beasties, were regularly employed as metaphors for male attraction, marriage, and even Christ the Redeemer, whereupon the unicorn’s innocent and gentle nature as a victim of wretched human violence will begin to feel oddly familiar to the spiritually-inclined.

The tapestry passed through several hands and households before being gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by none other than J.D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1973, and it has remained at the Met Cloisters ever since, on view in Gallery 17. Having been part of a prominent financier’s private collection certainly adds credibility to the work’s existence as an authentic medieval artifact, but would be difficult to fake provenance for considering the reputation of its previous owner. Best to seek guidance from a slightly more enigmatic reference.

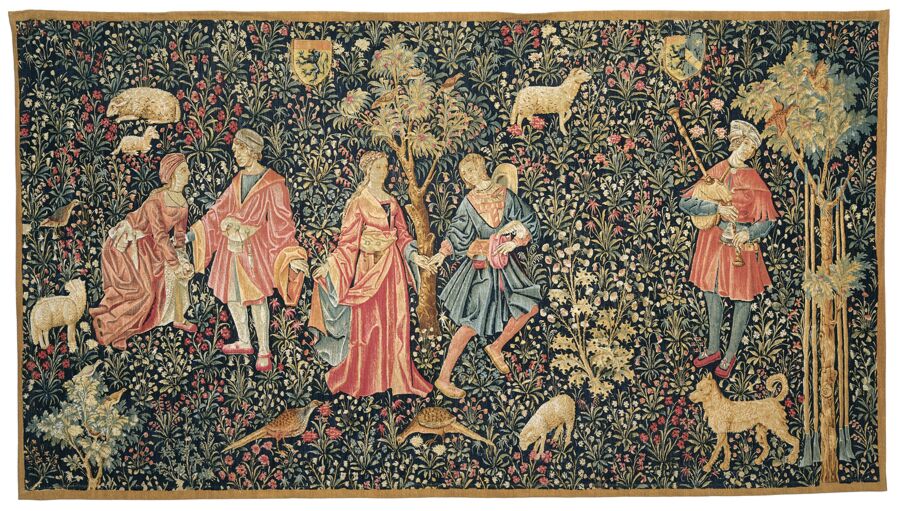

Known colloquially as The Lady and the Unicorn series, the six tapestries currently possessed by the Musée de Cluny in Paris, France, are yet another illustrious example of the medieval tapestry. The tapestries were likely created between the fourth quarter of the fifteenth century and the first quarter of the sixteenth century. Each piece represented a vital human “sense,” with touch, taste, sight, hearing, and smell represented by the first five, and a mysterious sixth, described as “À mon seul désir” or “To my only desire.”

The woman featured in each tapestry represents the “courtly and virtuous” qualities so commonly associated with women during the era of Christine de Pizan’s writings, in which aristocratic women were depicted in a uniquely positive light, carrying themselves powerfully and yet, at the same time, with peace in their hearts. The tapestries similarly employ visual metaphor, with the unicorn taking on a less saintly reputation than in the Unicorn Rests in a Garden. Rather, the unicorn in these pieces likely admonishes, in an almost playful way, the contemporary man’s salacious behavior.

The creator of these tapestries is also unknown and their provenance is even more elusive than that of the Unicorn Rests in a Garden piece. They may have been commissioned by Jean Le Viste IV (1432-1500) and inherited by his daughter, Claude, upon his death. After centuries of being hung in the Chateau Boussac, Creuse, in Limousin, France, the French government purchased the works and gifted them to what is now the Musée de Cluny in 1882, where they remain to this day. A rather simple provenance, but one with enough holes that a simple lie could slip through the cracks undetected.

❧ Step 4: Study Your Crime

A medieval forgery requires both the body and soul of an expert: a discerning eye to examine the visual clues that make up an authentic work, hands that can accurately and precisely craft each detail in as authentic a manner as possible, a sharp mind that can weave a tangled web of lies just convincing enough to throw any art market professionals off of your suspicious scent, and, of course, the charisma to confidently present a work as an authentic historical artifact, therefore injecting the spirit of a licit object into the fabrication.

An expert will know that medieval tapestries often fall into three to five categories: historical or narrative, religious, and secular or allegorical. Of course, the categories naturally blur together as various patrons and craftsmen employ different methods of storytelling to convey the tapestry’s core message. To produce a convincing piece, the theme of the tapestry should be relevant to medieval literature and art. We could choose to depict figures from Christianity, represented through allegorical facades. A unicorn is ideal, but perhaps too sensational. Remember, a successful forgery will not draw too much attention to itself.

We must also evade chemical analysis. Medieval tapestries are fragile, hence why so few have survived to the present day. Though chemical analysis is possible, it is extremely invasive and could risk damaging the delicate fabric. One study conducted during the conservation of the Heroes tapestries, currently owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, suggested that the dyes used to stain the fabric in such vibrant hues contained traces of lichen. Lichen dye sources were used frequently in the production of pigments for medieval artworks, therefore a successful forgery should employ fabric dyed with these particular sources.

Radiocarbon analysis is another method used to authenticate works and detect forgeries. If our forgery successfully passes every previous test–an expert’s scrutiny and a chemist’s deft tactics–an art market may, as a last ditch effort, turn to this method. It is most successfully used to detect forged paintings, typically helping to date the paint, canvas, or even wood of an original frame, and, when all else fails, the binder used for the paint.

Since radiocarbon dating targets organic materials, of which tapestries are made of, this could be the point where our forgery fails. It is imperative, then, that we find and use materials as close to their medieval counterparts as possible. Unless the inquiries into our piece’s authenticity come from more frugal individuals, as most auction houses and museum institutions will. They might hesitate to spend the money on radiocarbon dating, especially at the risk of destroying a potentially authentic work in the process.

The following video from GNS Science explains the process of radiocarbon dating:

Hyperspectral imaging is another process used to analyze the dyes used in historical tapestries, but are also destructive to the original materials. Chromatographic methods separate the molecular components within the dyes, making it easier for experts to characterize and identify them. This would require taking a sample from the back of a tapestry which could be detrimental to the piece’s structural integrity. There are less invasive approaches, such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS), both of which are micro-invasive and only use a small sample of material. But, again, acquiring this sample is the tricky part. If we hope to evade the suspicion of our buyers, we must rely on their unwillingness to both empty their pockets and risk devaluing the rarity they have their hearts (and wallets) set on.

❧ Step 5: Commit Your Crime…

…Hypothetically

In March of 2025, a man wandered into a Savers in Fairfax, Virginia, where he discovered a brilliant crimson tapestry hidden among the thrift store’s shelves. The man, Rafi Hoq, was immediately drawn to the gorgeous tangle of threads. He noted its intricate stitchwork atop a velvet background, characteristic of “Opus Anglicanum,” or “English work,” a method of needlework used for textiles in Medieval England. Hoq’s find, still marvelous in its own right, turned out to be a reproduction of an earlier work.

Finding a historical tapestry in a thrift shop is, without a doubt, unimaginable. But, it could work to a forger’s benefit. Planting a tapestry by donating it to a local thrift chain, sending a buyer in to stumble upon the work, having it appraised by careful experts, could be the storybook fairytale needed to pull off a heist like this. Or, one could simply finish up the work and take it to an auction house themselves, claiming to have found it among their grandmother’s antiquated odds and ends. With the proper paperwork, complete with a few convenient gaps in the provenance, a forged tapestry could very well sneak past suspecting professionals. All it would take is years and years of extensive research and some lovely calluses to mark your efforts.

❧ References ❧

Beresford, J. (2025). Man Convinced He Found Medieval English Tapestry in Virginia Thrift Store. (New York: Newsweek Digital LLC). https://www.newsweek.com/man-convinced-found-medieval-english-tapestry-virginia-thrift-store-2040067

Calà, E., Gosetti, F., Gulmini, M., Serafini, I., Ciccola, A., Curini, R., Salis, A., Damonte, G., Kininger, K., Just, T., & Aceto, M. (2019). It’s Only a Part of the Story: Analytical Investigation of the Inks and Dyes Used in the Privilegium Maius. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 24(12), 2197-.

Campbell, Thomas P. (2002). “European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400-1600.” Heilbrunn Timeline of History. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art). https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/european-tapestry-production-and-patronage-1400-1600

Campbell, Thomas P. “How Medieval and Renaissance Tapestries Were Made.” metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 Feb. 2008, www.metmuseum.org/essays/how-medieval-and-renaissance-tapestries-were-made.

Freeman, M. B. (1976). The Unicorn Tapestries. (Switzerland: Imprimeries Reunies), pp. 11-228.

Hajdas, I., Calcagnile, L., Molnár, M., Varga, T., & Quarta, G. (2022). The potential of radiocarbon analysis for the detection of art forgeries. Forensic Science International, 335, 111292–111292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2022.111292

Lackner, R. M., Ferron, S., Boustie, J., Le Devehat, F., Lumbsch, H. T., & Shibayama, N. (2024). Unraveling a Historical Mystery: Identification of a Lichen Dye Source in a Fifteenth Century Medieval Tapestry. Heritage, 7(5), 2370–2384. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7050112

Mallory, Sarah. “Making a Tapestry—How Did They Do That?” metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 18 Feb. 2014, www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/making-a-tapestry.

Royal Museums Greenwich Staff. “What Is a Tapestry?” Rmg.Co.Uk, Royal Museums Greenwich, www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/what-is-a-tapestry.

Shelley, W. (2009). “Text and Tapestry: The Lady and the Unicorn,” Christine De Pizan and Le Vistes. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/text-tapestry-lady-unicorn-christine-de-pizan-le/docview/2536400073/se-2?accountid=147094

Thomson, W. G., et al. (1973). A History of Tapestry from the Earliest Times Until the Present Day. 3rd ed. with revisions edited by F. P. & E. S, Thomson, EP Publishing.

Vlachou-Mogire, C., Danskin, J., Gilchrist, J. R., & Hallett, K. (2023). Mapping Materials and Dyes on Historic Tapestries Using Hyperspectral Imaging. Heritage, 6(3), 3159–3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030168

Williamson, J. (1986). The Oak King, the Holly King, and the Unicorn: the Myths and Symbolism of the Unicorn Tapestries. (New York: Harper & Row), pp. 3-230.