Since the early days of wine making it has been intertwined with fraud. Whether it be people mixing water with wine or putting new wine in old bottles, it has and it always will be around. It is estimated that around 20% of the luxury wine market is fake. Although not all is lost as a number of ways to combat this has appeared over the years such as Appellation Contrôleé, holographic stickers and other specialized packaging, ways of detecting synthetic dyes, radiation and carbon dating, looking at corks, and a number of other techniques to catch these fake bottles. But what if there was a way to get around them? To use this crime to our own benifit as wine sellers?

Outside of the people who targeted or who bought the wine, wine fraud has wider impacts than just the buyers and sellers. It has a chance to impact the market as a whole. From dissuading buyers from a specific type of wine or a brand or vineyard out of fear of being a victim of fraud to having a loss in faith in wine sellers as a whole. But on the flip side of this there can be a positive effect as there’s no such thing as bad publicity and prices can be driven up on the true product as it might be perceived as rare or hard to get a hold of after a forgery or some other scandle has come to light.

Given the state of California’s wine industry and the tariffs being imposed in the U.S. is about to hit the industry hard. Would it be so bad to turn to understand the mechanics behind fraud in order to help soften this blow? If not to soften the blow, why not use this as an opportunity to use the tricks of the trade to keep people from falling for the same scams time and time again.

The pursuit of wine is as much about the stories and legends as it is about the liquid itself.

– Benjamin Wallace

Forgers of the Past

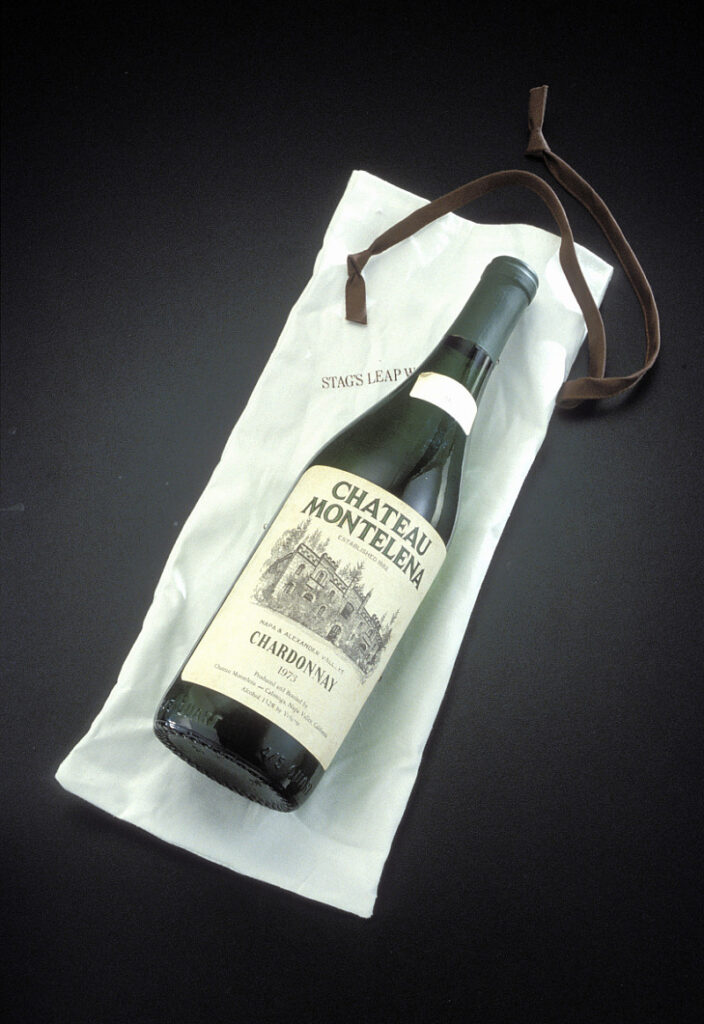

For this little… let’s say exercise, I wanted to forge a 1973 bottle of Chateau Montelena Chardonnay. The Smithsonian had one on display a bit ago, and it was quite the thing to look at. Due to its importance to the California wine industry, for really putting it on the map, it fetches quite the price. Especially if it can be made in mass. In theory all you would need to do is to take a bottle that looks convincingly like the original, print out a label and take some random mix of wine to fill the bottle up. But only a fool who wanted to be caught would do that. How would one go about this and not get caught? For that we would have to look at some of the more recent fraudsters to plague the wine market and pull a few pages from their book.

Rodenstock and The Jefferson Bottles

In recent decades there have been a handful of high caliber fraud cases such as Meinhard Görken, or Hardy Rodenstock as he was more widely known as, wine ring. He was the one responsible for the fiasco that was the Jefferson Bottles and a number of fake old wines that he pushed via wine tasting of his closest friends. This music producer and wine collector who “found” the Jefferson bottles, but truly doctored them by taking older wine bottles and engraving them with Jefferson’s initials and filling them up with a mix of newer wines. The key to his crime was the network that he had created within the wine community. By doing this he established a reputation and trust within this community and was able to push his “product” to those he deemed trustworthy and then slowly began to sell to the wider market. That is when he began to have issues, with challenges from the legitimacy of the Jefferson Bottles to the taste and flavoring of other high caliber wines.

Rudy Kurniawan

Another prime example of the rampant wine fraud within the community is Rudy Kurniawan. Similar to Rodenstock, Kurniawan created a tight knit community and established trust within the U.S. wine industry where he created forgeries of well known vintages and sold them at auctions. Considered one of the biggest wine forgers, Kurniawan sold more than 24.7 million at one auction and that was just the tip of the iceberg of his criminal career(Hellman). By taking the bottles, wax, corks, and labels from high end bottles of wine and filling them with a mix of cheaper wines Kurniawan was able to fool collectors into thinking they were buying the real deal. Kurniawan got caught because he started to create vintages of wines that never existed, resulting in a few loose ends that Auction Houses began to pull on in order to prove the providence of the bottles. The straw that broke the camel’s back was when bottles of 1945 and 1971 Clos St. Denis began to appear at auction houses. Vintages that never existed according to Laurent Ponsot, owner of the Domaine Ponsot vineyards. Ponsot states that his family only started to make wine in 1982 (Hellman). Once this was revealed others who had bought from began to find frauds in their own collections. Kurniawan became the first to ever be convicted with wine fraud and was sentenced for 10 years in 2013(Hellman and Frank). It’s rumored that a number of Kurniawan’s frauds are still floating around on the market, even today 12 years after his operations had been stopped.

The Sassicaia Incident

In 2015(Kuang, Yugan, Tolhurst, and Alston) there was another case of mass wine fraud of an Italian wine that is known as Sassicaia. A case of fake Sassicaia was found on the side of an Italian road with a note inside the case. (Tondo) On the note was a number, said number lead investigators to a warehouse that was filled with cases of the fake wine and lead them to eleven suspects responsible for running the operation. The operation was complex enough to be taking wine that was being produced in Sicily and putting them into bottles that were made in Turkey (Kuang,Yugan, Tolhurst, and Alston). On top of this they sourced their labels and wooden cases from Bulgaria, the result that was created was a striking copy of the 2015 Sassicaia, including the security measures that the company had used. The fake Sassicaia was almost undetectable to anyone who didn’t know what a real one looked like on top of what they had copied already but also the packaging was almost an exact replica of how real Sassicaia was packaged down to the paper the bottles were wrapped in (Kuang, Yugan, Tolhurst, and Alston). These bottles were sold at a 70% discount which allowed for the ring to make about 400,000 euros a month from the operation (Kuang, Yugan, Tolhurst, and Alston).

Where each of these forgers when wrong, other than being caught of course, is that they bit off more than they could chew. For Rodenstock it was in the way he made the Jefferson Bottles. From using incorect tools for the period for his engravings to faking his provedance enough to cause doubt from experts. He doubled down on his bottles and in the end that is what got him. Where Kurniawan went wrong was that he started to forge vintages that never existed in the first place. In the case of the Sassicaia Incident it was small screw up of someone leaving thier number behind on a create.

Old vs New

A bottle of wine is like a time capsule, preserving the history and craftsmanship of its era.

-Benjamin Wallace

Lets look back at the Jefferson Bottles for a moment to look at the importnace of the date of the wine that you may choose to forge. Because of the age in which the wine was bottled, the tools that went into creating the bottle would have been limited. Not difficult to recreate with the right techniques and a good amount of time, but alas he fell to the folly getting something done too quickly. Looking back to our little project there is an upside to not using such an old bottle. Because I, or you dear reader, may not have access to the materials needed to recreate the quarks of old wine bottles, let alone the manufacturing process. By choosing a more modern bottle it allows us to simply peel off the label of a cheaper bottle from that time and slap a new one on it. Another issue with older bottles, especially those that predate World War II, is the amount of radiation they may have been exposed to. There is no way around this kind of dating, unless you use period specific materials.

One thing that we can learn from all of them is that reputation and connections are incredibly important in order to sell a fake. Rodenstock had gained notoriety through his exclusive tastings and the collection that he came to have. With this he was able to sway opinions about the bottles that he was selling. With Kurniawan it was his network and the fact that he gained noteriaty from his ability to sell people diffrent wines. Networking is incredibly important with this kind of work. You need to establish yourself as a trust worthy person to those outside of your “inner circle”. I, dear reader, am a well known wine seller within my own groups, they trust me enough to sell them good quality, and authentic wines. They would be none the wiser if I slipped a fake or two into the vintages that I’ve sold them.

Money can buy many things, but it can’t buy taste.

– Benjamin Wallace

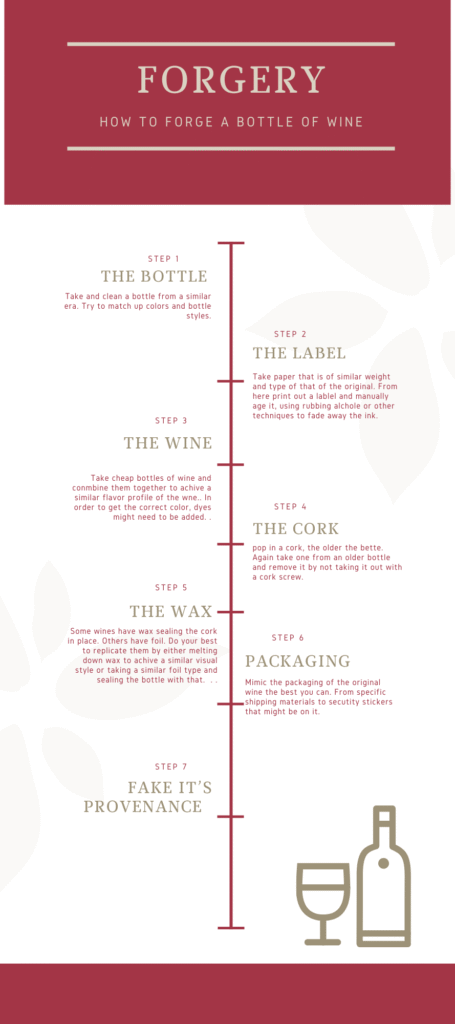

Creating the Bottle

If I were to forge a bottle of wine, not saying that I would or that I have after all this is just an exercise, this is how I would do it. First I would source bottles from other wines that were made in the 70’s yet lower caliber to be cheap enough that a profit could be turned from this. Labels were printed out on paper that was nearly identical to the true Chateau Montelena labels. The paper was made to look aged by a number of methods, a few with tea stains, some had extremely thin layers of watercolor brushed over them all in an effort to make the paper look aged. From here the paper is placed into a printer in order to print the vineyard’s labels and then left in a number of situations in order to make them look authentic. Many of the bottles had faded or missing ink that was removed via a sand eraser and small amounts of acetone. From here the bottles are filled with a mix of different Chardonnays in order to get an almost replicated flavor to this vintage, although from the looks of it this mysterious forger was aiming to target collectors and not those who were aiming to drink the wines. The bottles were corked with corks from the 70’s and then a foil was applied to the top of the bottles in order to look like “brand new” or original bottles of this vintage.

Sources Used

Benson, Robert W. “The Paris Tasting: Evidence, Jury, and Verdict.” American Bar Association Journal, vol. 62, no. 12, 1976, pp. 1640–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25727914. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025.

D.W. Lachenmeier,

21 – Advances in the Detection of the Adulteration of Alcoholic Beverages Including Unrecorded Alcohol, Editor(s): Gerard Downey, In Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Advances in Food Authenticity Testing, Woodhead Publishing, 2016, Pages 565-584, ISBN 9780081002209, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100220-9.00021-7. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081002209000217) Accessed 10 April. 2025

Grgich, Miljenko. 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay. 1973. Smithsonian, https://www.si.edu/object/1973-chateau-montelena-chardonnay:nmah_1297105. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025

Hellman, Peter, and Mitch Frank. “Accused Wine Counterfeiter Rudy Kurniawan Guilty in Landmark Court Case.” Wine Spectator, Wine Spectator, 18 Dec. 2013, www.winespectator.com/articles/accused-wine-counterfeiter-rudy-kurniawan-guilty-in-landmark-case-49396 . Accessed 8 Mar. 2025

Hellman, Peter. “Firm Alleges Rudy Kurniawan Sold It $2.45 Million in Fake Burgundy, and Wine Merchants Helped.” Wine Spectator, Wine Spectator, 25 May 2016, www.winespectator.com/articles/firm-alleges-rudy-kurniawan-sold-fake-burgundy. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025

Herrero-Latorre, Carlos, et al. “Detection and Quantification of Adulterations in Aged Wine Using RGB Digital Images Combined with Multivariate Chemometric Techniques.” Food Chemistry: X, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 5 July 2019, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6694846/. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025

Hira, Anil. “From Industrial Strength to World Class: Gallo and Mondavi’s Contributions to the California Wine Industry.” California History, vol. 92, no. 4, 2015, pp. 48–72. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/ch.2015.92.4.48 . Accessed 8 Mar. 2025.

King, V. (2019). Wine, Fraud and Expertise. UC Irvine. ProQuest ID: King_uci_0030M_16000. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m5dc38bt. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/06h3278v Accessed 3 April. 2025

Kuang, Yuyan, Tor N. Tolhurst, and Julian M. Alston. “Unraveling the Economic Impact of Wine Counterfeiting: An Analysis of the Sassicaia 2015 Scandal and Its Consequences.” _Journal of Wine Economics_ 19.4 (2024): 365–374. Web. Accessed 8 April. 2025

Tondo, Lorenzo. “Italian Police Seize 4,000 Bottles of Counterfeit ‘super Tuscan’ Wine.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Oct. 2020, www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/15/italy-police-seize-bottles-counterfeit-super-tuscan-wine-bolgheri-sassicaia . Accessed 8 Mar. 2025

Wallace, Benjamin. The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine. Three Rivers Press, 2009. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025