Stealing the Chessmen

The Team

- Leader (me)

- The Hacker

- The Lookout(s)

- The Muscle

- The Getaway Car Driver

Getting to Scotland

I need to find a job or internship at the Museum nan Eileen or with a company strongly associated with it. I will create a fake identity for this. Once the position is accepted, I need to get to Scotland. Before arriving to Stornoway, I will set up a meeting with one of the curators/managers who works at the British Museum in London. I will say the point of this meeting is an informal interview about careers in museums, but my goal is to get a copy of their fingerprints to plant around the crime scene to misdirect investigators. After our discussion, I will purchase replicas of the chessmen from the museum gift shop with cash. These will be our replacement pieces.

Building Trust

Once in the role, I need to build trust with the staff at the museum. This will eventually give me more time alone without supervision with the various artifacts in the museum, including the Lewis Chessmen. I will be able to learn the ins and outs about the museums security systems, peak hours, when other staff are present, etc. Once this trust is established, if the rest of the team has not arrived in the country, this will be the time for them to do so.

The Heist and the Getaway

During the night of Hogmanay, the Scottish celebration for New Year’s, will probably be the best time to carry out the heist. Security will be limited as celebrations go on and most will be in more urban areas. In a car we will all arrive at the museum. I will (ideally) have keys in hand for the museum by this point which will negate the need to lockpick or just breaking in. Our hacker will then either break into the security system to shut it down completely, or can erase the data for the night. The driver and hacker will remain in the car for a speedy retreat, ready by the museum entrance facing the direction of escape. They are also going to serve as lookouts for the Lews Castle grounds. The rest of the team and I will make our way inside. The museum is a newer building attached to Lews Castle. It’s rectangular in shape with the Lewis Chessmen in the back of the building near the middle of the room. From what I’ve learned there are only a few cameras in the museum itself. Being a smaller institution this is not surprising. The Chessmen are in a glass case on individual clear pedestals. Breaking the glass case would make it too obvious that the chess pieces are gone/fake, so we will need to get into the case legitimately. The keys are likely to be in a nearby curator’s office. Once in the case, I’ll simply swap out the real chessmen for the souvenirs from the British Museum and close the case back up. While I’m doing this the others, while also keeping a lookout, will be planting the fingerprints taken earlier to provide a false lead to investigators. Once the authentic pieces are safely stored away in the packaging of our souvenirs, the casing will be replaced on the pedestal and those of us inside the museum will meet the two in the car. Our next step is to ditch the car and take a flight to Reykjavík, Iceland and then back to the United States.

The Aftermath

If all goes according to plan, we will be long gone by the time it’s discovered that chessmen on display at the Museum nan Eilean are replicas bought at the British Museum gift shop. The planted fingerprints will hopefully give us enough time to get off the grid and become ghosts as it should get the police off our trail for a little while. If the heist is publicized enough, the Scottish people might be very heated, especially those from the Isle of Lewis. This heist will have ripple effects, not only impacting the Scottish but also any other institution that has made long-term loan agreements with the British Museum. Likely, the British Museum would terminate those agreements and request those items be returned.

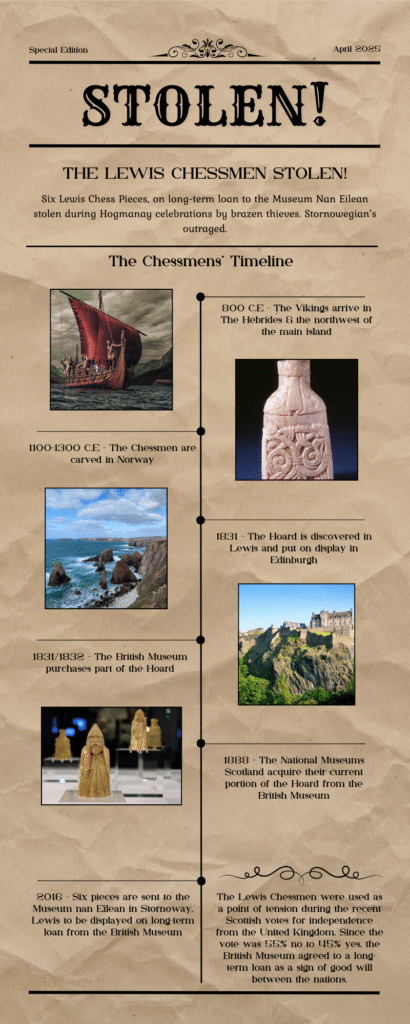

The Lewis Chessmen

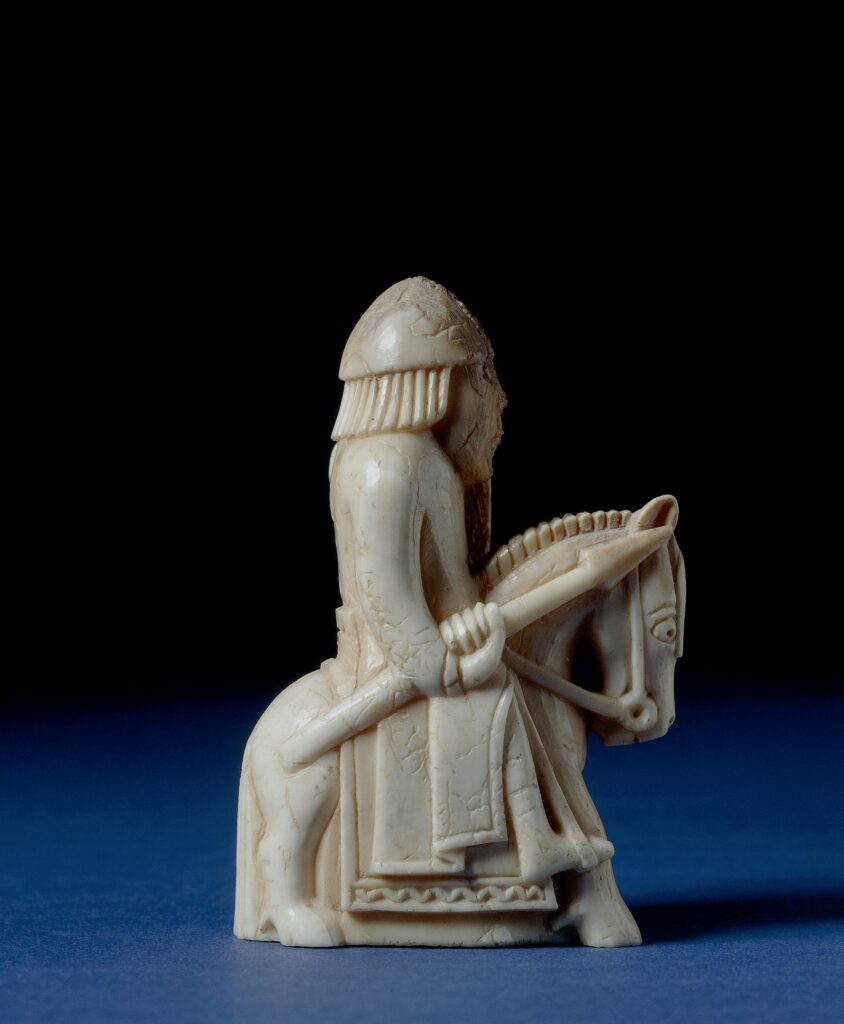

The Lewis Chessmen in Stornoway, Lewis are six of the original (known) 94 pieces of the Hoard found in Uig, Lewis in 1831. They are small (the tallest being only 10cm) chess pieces carved of walrus ivory and some of whale tooth.

Why These Artifacts?

While small in stature, these chess pieces have a large cultural significance to the Scottish people. Not only are they something that Scotland is proud to have found in their country, it also is a remnant of their Norse heritage, something many Highlanders are proud of. The Chessmen also played a role in the recent 2014 vote for Scottish Independence. As the close majority was a vote of “no” to leave the United Kingdom and Commonwealth, it was decided that some Scottish artifacts should be returned to Scotland. However, rather than outright giving more pieces to the country, the British Museum put six pieces on long-term loan to the Museum nan Eilean in 2016 in Stornoway, Lewis, close to the beach where the hoard was originally found in 1831.

Works Cited

Arraf, Jane. “Hobby Lobby’s Illegal Antiquities Shed Light on a Lost, Looted Ancient City in Iraq.” NPR, NPR, 28 June 2018, www.npr.org/2018/06/28/623537440/hobby-lobbys-illegal-antiquities-shed-light-on-a-lost-looted-ancient-city-in-ira.

Atkinson, Rebecca. “Lewis Chessmen to Return to Western Isles.” Museums Association, 14 Aug. 2020, www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2012/06/14062012-lewis-chessmen-returned-to-western-isles/#.

Caldwell, David H., et al. The Lewis Chessmen Unmasked. National Museums Scotland (NMS), 2010.

Carter, Stephanie L. “What Are They Worth?: A Holistic Exploration of the Lewis Chessmen and the Values Placed upon Them.” What Are They Worth?: A Holistic Exploration of the Lewis Chessmen and the Values Placed upon Them, The University of Edinburgh, University of Edinburgh, 2021.

Chen, Frederick, and Rebecca Regan. “Arts and Craftiness: An economic analysis of art heists.” Journal of Cultural Economics, vol. 41, no. 3, 2017, pp. 283–307, https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.nau.edu/stable/48698164.

Durney, Mark. “How an Art Theft’s Publicity and Documentation Can Impact The Stolen Object’s Recovery Rate.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, vol. 27, no. 4, 2011, pp. 438–448.

“Gardner Museum Theft.” Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, www.gardnermuseum.org/organization/theft. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Knelman, Joshua. “A Brief History of Art Theft.” Queen’s Quarterly, vol. 118, no. 2, 2011, p. 222.

Long-Term Loans | The British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/our-work/national/uk-touring-exhibitions-and-loans/long-term-loans. Accessed 6 Apr. 2025.

Marica, Irina. “Romanian History Museum Director Dismissed after Dutch Exhibition Theft.” Romania Insider, 29 Jan. 2025, www.romania-insider.com/national-history-museum-director-dismissed-dacian-theft-2025#:~:text=Culture%20minister%20Natalia%20Intotero%20announced,the%20exhibition%20in%20the%20Netherlands.

Middlemas, Keith. The Double Market: Art Theft and Art Thieves. Saxon House, 1975.

Parker, Alan. “Lews Castle Museum.” YouTube, youtu.be/3ZYqle-Xs-c?si=H-F5jqmGyk0EhqCV. Accessed 5 Apr. 2025.

Sassoon, Donald, and Leonardo. Becoming Mona Lisa: The Making of a Global Icon. Harcourt, 2003.

Stratford, Neil. The Lewis Chessmen and the Enigma of The Hoard. British Museum Press, 1997.

All pictures of individual chess pieces are provided by the British Museum

The Individual Pieces