The Crime

Portrait Head; Unknown Artist, 300-150 BC, Hellenistic Period, said to be from Alexandria (Egypt), marble, British Museum, 1872,0515.1; https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1872-0515-1

In the following document, I detailed how and why I made the choices I did in order to successfully create a Hellenistic sculpture forgery which was then sold to a private buyer. I drew inspiration for the project from two different works of art. The first piece was a Hellenistic period marble head of Alexander the Great [above] that is housed in the British Museum. I used this piece for stylistic inspiration for the forgery.

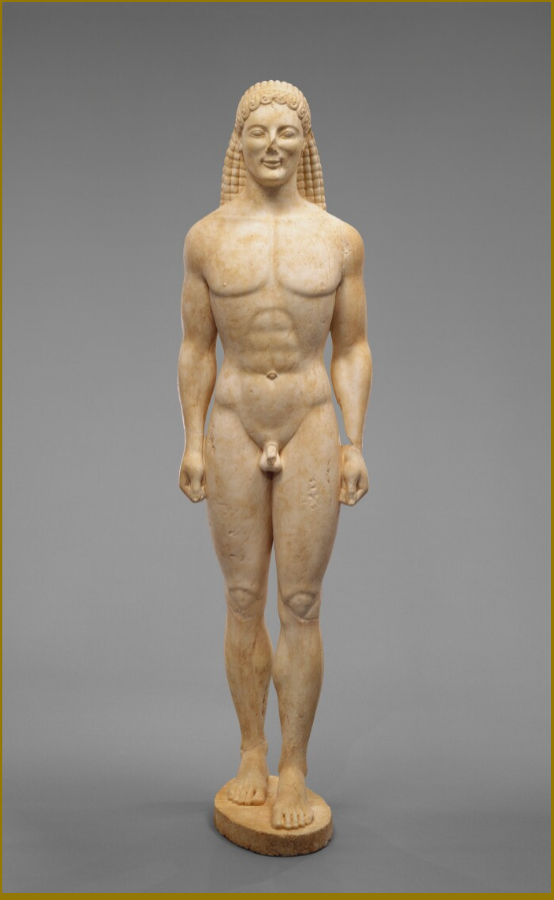

Korous; Unknown artist, about 530 BC or modern forgery, Archaic Greek, marble, Getty Museum, 85.AA.40; https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103VNP

The other work that I drew inspiration from was a Korous that is currently held in the Getty Museum. I am not taking stylistic inspiration from this work, but rather narrative inspiration. It is highly debated whether or not this work is a forgery. On the Getty’s website, the date of this piece is listed as “about 530 B.C. or modern forgery.” I pulled from arguments regarding this piece when considering what would and could be tested for authenticity.

For my crime, I intend to exploit the art market to pull off my forgery. In a class lecture, it was stated that the art market was created to feed an economic demand and as long as there is this demand, the art market (especially its illicit aspects) will continue to thrive. Going into this, I knew that catering to the market was a necessity. This includes knowing who is willing to pay the most for my forgery.

It is important to look at demand and there has been proven demand for antiquities by private buyers. The piece that I am emulating is dated to 30-150 BCE, which makes it considered an antiquity. Although I am not selling to a museum, in the case of the Getty Korous, there was evidence of financial gain for selling antiquities. The Getty accessioned this piece in 1985 after buying it for between seven and nine million dollars. This demonstrated that larger institutions are willing to buy Greek antiquities for a large sum which supports my reasoning for forging a work in a similar style, albeit from a later period than the korous was from. Additionally, Sotiriou found in their research that there is a large number of Greek antiquity forgeries on the market and that the buyers are almost entirely from the upper class.

Video from the BBC, “Will the Elgin Marbles return to Greece- BBC news”

In addition to the financial payout, I also believe that there is cultural value to Greek antiquities that would also support my reasoning for this crime. Greek antiquities have been more prevalent in the cultural zeitgeist due to new coverage in multiple countries surrounding repatriation efforts. The BBC, The Guardian, and ARTnews.com all have written articles, such as the video above, on Greek antiquities in the past three months. This is why I chose Greek antiquities over those from other countries such as Egypt or the Americas. People in the general public have been hearing about these works and so I believe that institutions would be more willing to purchase objects of this sort, resulting in a larger payday, which is ultimately the primary motivation.

“Forgery of a Hellenistic or Roman Marble Aphrodite.” Museums Collections, University of Delaware.

https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/things-arent-what-they-seem/exhibition-item/forgery-of-a-hellenistic-or-roman-marble-aphrodite/

For stylistic analysis, I drew heavily from the University of Delaware’s online exhibition, Things Aren’t What They Seem. One work they use in their catalog is a forgery of a Hellenistic Marble Aphrodite. This statue was proven to be a fake for a number of reasons. First, there are the proportions to consider. The University of Delaware’s sculpture had bodily proportions that align with a human model. However, in the Hellenistic period, it was more common for the ideal human form to be constructed. I chose to emulate a sculpture of Alexander specifically because he was associated with distinctive characteristics (clean-shaven, royal diadem, and longer hair) which would make it more distinguishable for connoisseurs determining the authenticity of my forgery. When emulating these distinctive characteristics, I made sure to let my partner know that the sculpture should be an ideal male form and not a realistic one.

In Johnson’s public scholarship, there was a point about the type of material used in Hellenistic forgeries. Hellenistic sculptors most commonly used coarse grained marble, but forgers typically get caught due to using fine grained marble. Utilizing the correct material is the first step in creating this forgery. Another aspect to consider was materials behavior. A critical part of material behavior is the aging characteristics for a work of art . The “damaged” areas look intentional and meant to emulate a broken sculpture fragment. There are no examples of artists in antiquity who created fragments (such as just a head or torso). Since, my forgery is also a fragment, I considered this an important consideration. My way to get around this is sculpting a head and torso and then breaking off just the head. This evokes a naturalistic break as opposed to one curated by a forger. Researchers attempted to replicate the surface of the Getty Korous using 200 different methods. There were a few of these trials that appeared similar, but did not hold up under elemental analysis. This means that my forgery would not hold under rigorous scientific testing on a material level. However, the class has had a number of talks from museum professionals, and many of them have emphasized the issues of scientific testing. It is expensive and results in damaging the art. I believe that if my provenance and connoisseurship arguments are strong enough, then the buyers would be unwilling to expend the additional cost and potentially harming an original Hellenistic statue.

Works Cited

Garvin, Kaitlyn. “The Case of the Getty Kouros.” A Genuine Dilemma: The Authenticity of the Getty Kouros (2015). https://arthistorykmg.omeka.net/about

Getty Museum. “Korous.” Museum Collection. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103VNP

Goulandrē, Hidryma Nikolaou P., and Mouseio Kykladikēs Technēs, eds. The Getty Kouros Colloquium: Athens, 25–27 May 1992. Getty Publications, 1993.

Hick, Darren and Jonathan Gilmore. “41. Forgery and Authenticity.” The Routledge Companion to the Philosophies of Painting and Sculpture. Routledge, 2023.

Johnston, Alexander. “Forging the Ancient World.” Things Aren’t What They Seem: Forgeries and Deceptions from the University of Delaware Collections (2018). https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/things-arent-what-they-seem/home/forging-the-ancient-world/

Pratt-Sturges, Rebekah. “The Art Market” Topics in Museum Studies, Northern Arizona University (2025).

Sloggett, Robyn. “Unmasking art forgery: scientific approaches.” The Palgrave handbook on art crime (2019): 381-406.

Sotiriou, Konstantinos-Orfeas. “The F words: frauds, forgeries, and fakes in antiquities smuggling and the role of organized crime.” International Journal of Cultural Property 25, no. 2 (2018): 223-236.