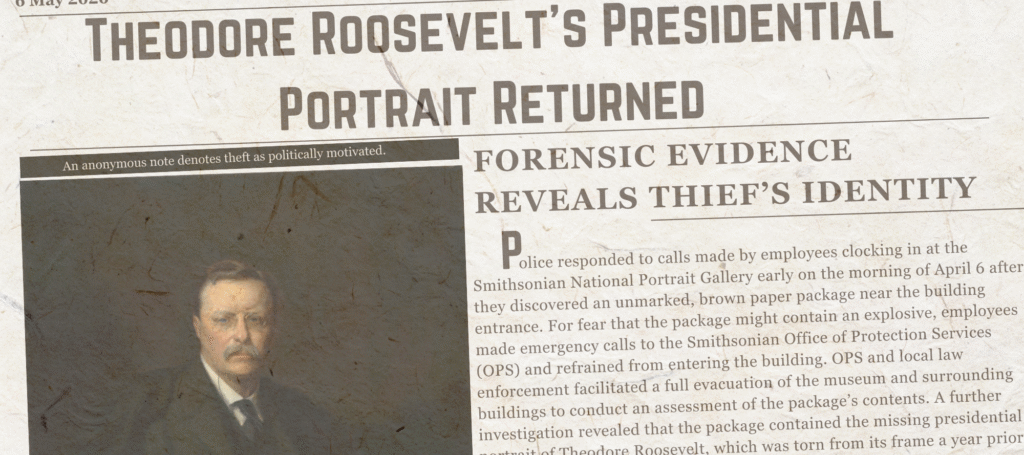

Last month, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery received Theodore Roosevelt's presidential portrait in an inconspicuous brown package placed at the employee entrance. As I had hoped, the package caused quite a stir in the Washington D.C. area. and later, throughout the world as headlines hit the news outlets.

Unfortunately for me, this mass media attention came at the cost of my freedom. If it had not been for my carelessness in leaving traces of my fingerprints on the package's brown paper wrapping, the FBI and Smithsonian Office of Protection Services might still be looking for me.

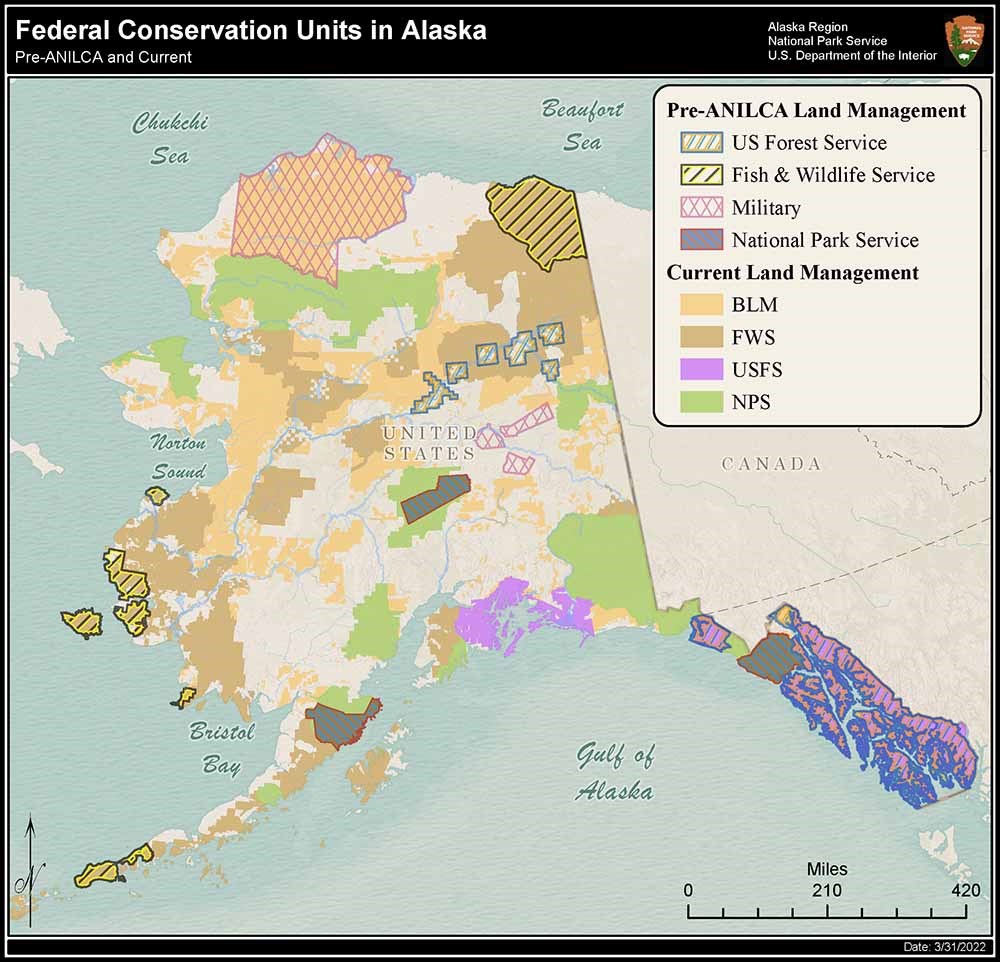

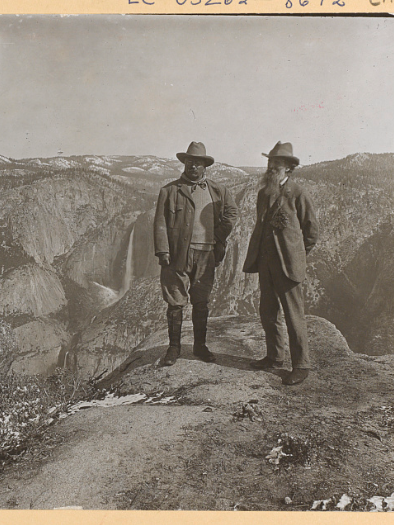

The word is out and there is undeniable evidence against me, so I must confess. I stole Theodore Roosevelt’s presidential portrait from the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. last spring (FIGURE 1). This was my protest against President Donald Trump’s executive orders threatening the accessibility, beauty, and health of the United States’ federal lands. Roosevelt is rolling in his grave as the current administration disregards the spirit of Roosevelt’s presidency, an era in which the nation’s leadership valued mindful environmental conservation practices.

In completing this theft, Roosevelt became my hostage. A series of anonymous notes that I sent to the National Portrait Gallery communicated my demands for the current administration to rescind new drilling plans, and if my demands went ignored, I promised that I would destroy the painting. Did I really think that my heist would be effective enough to convince the government to reconsider these actions? No, I did not. I did hope that my story would reach popular media, bringing these urgent environmental issues to the top of every social media-user's algorithm. I hoped to grab your attention and convince you all why this is a worthwhile cause, because our voices combined may eventually be enough to effect change. Now that I have your attention, I hope you will understand my motivation...

Our Public Lands are Under Attack

In favor of economic benefit, the current administration’s intensive resource extraction plans infringe upon the health and safety of the ecosystems, human communities, and wildlife of the United States’ public lands.

In President Donald Trump's recent executive order of January 20, 2025, he stated plans to expand drilling operations on American public lands previously protected by “burdensome and ideologically motivated regulations." He claims that these regulations have hindered the nation’s use of untapped resources, limited job availability, and drastically increased energy costs in recent years.

The Secretary of the Interior, Doug Bergum, addressing a more recent executive order, stated that the administration will exploit energy sources in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR).

Congress established ANWR in 1980, which protected over 100 million acres of Alaskan lands, including the 20 million acres of ANWR, to protect migratory and resident wildlife species, wilderness and recreation areas, and the ancestral lands of the Iñupiat and Gwich'in Indigenous people. These actions warrant outrage from the nation’s affected populations, environmentalists, and humanitarians.

Executive Order: Unleashing American Energy

Section 1. Background: “America is blessed with an abundance of energy and natural resources that have historically powered our Nation’s economic prosperity. In recent years, burdensome and ideologically motivated regulations have impeded the development of these resources, limited the generation of reliable and affordable electricity, reduced job creation, and inflicted high energy costs upon our citizens…” – President Donald Trump, Unleashing American Energy.

Executive Order: Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential

Section 1. Background: “The State of Alaska holds an abundant and largely untapped supply of natural resources including, among others, energy, mineral, timber, and seafood. Unlocking this bounty of natural wealth will raise the prosperity of our citizens while helping to enhance our Nation’s economic and national security for generations to come…” -President Donald Trump, Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential.

Secretary’s Order No. 3422: Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential

Sec. 3. Background. “President Trump declared that unlocking Alaska’s massive bounty of natural wealth (Alaska is larger than our smallest 22 States combined) will raise the prosperity of our citizens and help our Nation’s economic and national security for generations to come by,

among other policies:

a. fully availing itself of Alaska’s vast lands and resources for the benefit of the Nation and the American citizens who call Alaska home;

b. efficiently and effectively maximizing the development and production of the natural resources located on both Federal and State lands within Alaska;

c. expediting the permitting and leasing of energy and natural resource projects in Alaska (including specifically for the rights of way and easement for roads that enable this development to occur; and

d. prioritizing the development ofAlaska’s liquified natural gas (LNG) potential, including the sale and transportation ofAlaskan LNG to other regions ofthe United States and allied nations within the Pacific region.” – Doug Bergum, Secretary of the Interior, Secretary’s Order No. 3422: Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential.

Alaska Conservation Foundation: “Save the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge,” Video Transcription

Narrator: The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is America's largest and most wild natural environment, the cradle of life for millions of animals, including the vast, porcupine caribou herd, which migrates here every year to give birth to its young safe from human disturbance. Gwich’in people call this “the sacred place,” where life begins.

Charlie Swaney: For the caribou, that’s where life begins for them, where they take their first breath of fresh air, where they take their first bite to eat, first time seeing this world. That’s where it’s all at, right there. They continue to go there year after year after year because everything is right for them there.

Narrator: The Gwich’ in have relied on these migrating caribou for their very survival and cultural identity for thousands of years, and still do.

Charlie Swaney: there’s no way that we could live off of store-bought food year-round here, and that’s why it’s so important for what’s out here, mainly with the caribou, and this is what we try to protect.

Narrator: now, the survival of all these animals, the Gwich’in way of life, and the arctic refuge itself, our nation’s last, untouched sanctuary of nature are in grave and immediate danger, threatened by unnecessary oil and gas exploration and industrial development in the heart of this sacred place. We need to stand against oil exploitation, and stand for nature and the human right when they need us most. That time has come. Please join us to preserve the refuge while we still can now and for generations to come.

Bernadette Demientieff: We made a pact that we would always take care of them if they always took care of us. Now it’s our turn, and we will not back down, and we are not going to make it easy, because this is our home. We were here and we are not going anywhere. You know, this is our home, this is who we are, and you can’t take that from us.

The current administration will exploit the United States’ public lands. Each order, effective immediately, rescinds pre-existing environmental protections and shares a common goal of benefiting the nation’s economy by lowering energy costs. This objective largely overlooks the value of ceremonial lands, ecological health, recreation, and wildlife populations.These actions warrant outrage from the nation’s affected populations, environmentalists, and humanitarians. The United States’ public lands are under immediate threat due to this administration’s orders, making the call for change especially urgent.

Why Roosevelt?

I stole Roosevelt’s presidential portrait to protest the current administration’s plans to exploit lands that Roosevelt strove to protect.

Each presidential portrait in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery bears cultural significance associated with the individual and their impact on American history.

According to a curator at the institution, a presidential portrait “encapsulates” the sitter's personality and values, as well as American history respective to their tenure. As such, Roosevelt’s presidential portrait represents previous strides toward environmental conservation and mindful resource use in this nation’s history.

The Hungarian artist, Philip Alexius de László (1869-1937), painted Roosevelt’s original presidential portrait (see FIGURE 1)in 1908 as a commission from Roosevelt’s close friend, Lord Arthur Lee (1868-1947). In 1938, Lee gifted László’s portrait of Roosevelt to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where the museum currently stores the object in its archives. As a commission from the Theodore Roosevelt Association (TRA), the American artist Adrian Lamb (1901-1988) painted the portrait’s reproduction using oil on canvas in 1967. The National Portrait Gallery later received Lamb’s reproduction as a gift from TRA.

Lamb’s 1967 portrait of Roosevelt was on display in the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent exhibit, “America’s Presidents,” with the accession number NPG.68.28, and is now likely undergoing intense and highly precise restoration procedures considering that I cut the painting away from its frame and rolled it up to remove from the gallery during my heist.

Inspiration

Two notable cases inspired this form of protest, including art heists associated with the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in 1974 and the contemporary art installation Dead Man’s Switch by Andrei Molodkin. Both cases used artworks as “hostages,” threatening their destruction if politically-motivated requests were not met. This practice uses an institution’s value for cultural property as leverage for a specific outcome.

The IRA Heists

In February of 1974, a Vermeer painting, The Guitar Player, was stolen from the Kenwood House in London. Following the painting’s disappearance, the London news publisher, The Times, received an anonymous letter demanding the freedom of Irish Republican Army (IRA) members, Dolours and Marian Price, from the Brixton prison (Keefe 156). The unnamed thief promised the painting’s return if these expectations were met.

In a second art heist associated with the Price sisters’ release from prison, IRA member Rose Dugdale forcibly entered the private Russborough House in Ireland with three other IRA members. They stole 19 paintings, a Velázquez, a Vermeer, a Rubens, a Goya, and a Metsu among them. A week later, the thieves produced a ransom note demanding the Price sisters' freedom or else they would destroy the masterpieces.

Both cases are examples of politically motivated art heists in which thieves demanded a specific outcome rather than a monetary ransom. I emulated this process by producing an anonymous ransom letter, demanding that the Trump administration rescind plans to expand drilling and logging on public lands for the return of Roosevelt’s presidential portrait.

Andrei Molodkin’s Dead Man’s Switch

The Russian artist Andrei Molodkin acquired 16 artworks of notable artists, including Picasso, Rembrandt, and Warhol, and locked them inside a safe equipped with a “self-destruct” button. Molodkin stated that he would destroy the masterpieces if the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was extradited to the U.S. and died in custody.

Like Molodkin’s threat to destroy his hostage artworks, I stated my intentions to torch Roosevelt’s portrait if the government ignored the public’s outrage at the exploitation of American public lands. In addition, I used the public's value for cultural heritage as leverage to reach an end.

Similar to the IRA art heists, the government ignored my demands. I will admit that I was tempted to sell the portrait on the illicit market, but I reconsidered. According to the economists Antonio Nicita and Matteo Rizzolli, a famous stolen painting is less likely to sell on the black market because potential buyers are typically not willing to assume the risk of getting caught with the object.

Drawing inspiration from the first art heist associated with the IRA, I chose to return the painting to the National Portrait Gallery anonymously. This is because I was not satisfied with the publicity of my demonstration. As. I hoped, the painting's return brought more publicity to my case and thus stirred more interest in my demonstration.

Methods

Are you feeling inspired by my story now? Perhaps you will be the next art thief motivated by a political agenda. Maybe you will still Albert Bierstadt's Among the Sierra Nevada, California or Thomas Moran's The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone to demonstrate the value that the U.S. government once placed on the nation's wilderness areas. I have to warn you not to be too confident now, as the Smithsonian Institution has already dealt with my case and — as the host of the National Conference on Cultural Property Protection — is most certainly taking measures to prevent future heists and warn other institutions against the threat of politically-motivated art thieves. If you must follow in my footsteps, read ahead to learn my methods and what the Smithsonian Institution has dealt with.

The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery utilizes its Office of Protection Services (OPS) unit to protect cultural property across each of the institution’s museums in Washington D.C., including the National Portrait Gallery. OPS employs over 850 law enforcement officers and security personnel to promote a safe environment for the Smithsonian Institution’s visitors and employees, as well as to protect the institution’s vast collection of objects. An OPS web page describing the roles of OPS guards suggests that security personnel monitor Smithsonian museums at all hours and oversee each facility’s alarm system. The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s alarm system and OPS security personnel were the primary obstacles to overcome in my heist.

Museum employees with exclusive access to the institution’s collections and security system have conducted the majority of art thefts in recent years. Knowing this, I frequented the Smithsonian museums in Washington D.C. for several months and made my acquaintances with numerous OPS guards to find a trusted employee with access to the National Portrait Gallery’s alarm and surveillance system well in advance of this heist. I targeted an individual who agreed with my political motivations and was willing to be an accomplice for this heist. My accomplice, after facilitating my entrance into the building, granted me access to the central alarm and surveillance system to disable their devices.

To prevent unnecessary suspicion and to remove the painting from the gallery, I have drawn inspiration from the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum heist. Two individuals disguised as police officers entered the Gardner Museum after 1:00 AM, tied up the museum security guards in the basement, and proceeded to commandeer numerous artworks throughout the galleries, even cutting several paintings away from their frames. Like these thieves, I conducted my heist during closing hours and disguised myself as a Security Operations Division guard associated with OPS. With my disguise, I aimed to prevent other security guards on the scene from becoming suspicious of my presence in the building before commandeering the painting.

With the security and and surveillance systems disabled, my accomplice distracted other security guards on site by alerting them to the "malfunctioning" security system. I proceeded to the "America's President's" exhibit on the second floor of the National Portrait gallery, cut Roosevelt’s portrait away from its frame using a scalpel, and rolled the canvas into a tight scroll. After hiding the painting in my pants pocket, I made a quick escape down the stairwell to the left of the “America’s Presidents” exhibit entrance and exited the building on “F Street” from the nearest emergency exit. From there, I met my getaway driver, who whisked me away without being seen.

A Call to Action

Take caution when recruiting an accomplice. When the Smithsonian Institution discovered the painting had gone missing, my accomplice attempted to expose me for fear that he might become discovered as an accessory to the heist.

I was initially fortunate that he had no evidence to prove his claims. That is, until forensic investigators found my fingerprints on the brown paper that I had packaged the painting in for its return.

Being locked in a prison cell now, I am calling upon the nation's affected populations, environmentalists, and humanitarians to continue fighting for our public lands. Roosevelt is still rolling in his grave, and it is now up to you to allow him to rest.

Bibliography

Agama, Susana P. The Art of Art Theft Retrieval. 2016. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

American Museum of Natural History. “Collection: Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) / UR ‘P.A. Laszlo/Washington’ | Archives Catalog | AMNH,” 2016. https://data.library.amnh.org/archives/repositories/3/resources/7972.

Barber, James. Theodore Roosevelt, Icon of the American Century. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Bergum, Doug. “Secretary’s Order #3422: Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential.” The Secretary of the Interior, February 3, 2025. https://www.doi.gov/sites/default/files/document_secretarys_orders/so-3422-signed.pdf.

Conference Of Governors, and United States President. Proceedings of a Conference of Governors. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908. Periodical. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/sf82007077/>.

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “The Theft: What Is Known about the Isabella Stewart Gardner Heist—the Single Largest Property Theft in the World,” n.d. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/about/theft-story.

Keefe, Patrick Radden. Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland. First Anchor Books edition, Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2019.

Keller, Steven R. “The Quandaries of Museum Security.” The Journal of Museum Education, vol. 20, no. 1, 1995, pp. 10–11. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40479484. Accessed 14 Apr. 2025.

Lawson-Tancred, Jo. “$45 Million Worth of Art Is Being Held Hostage for Julian Assange’s Life | Artnet News.” Artnet News, February 14, 2024. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/julian-assange-andrei-molodkin-2433258.

LAYNE, STEVAN P. “Closing the Barn Door: Dealing with Security Issues.” History News, vol. 57, no. 4, 2002, pp. 1–6. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42653878. Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.

Lunde, Darrin. “Beauty and Tragedy in the Wilderness: The Naturalism of Theodore Roosevelt.” Theodore Roosevelt, Naturalist in the Arena. Edited by Char Miller and Clay S. Jenkinson. University of Nebraska Press, 2020. EBSCOhost.

Miller, Char. “Play, Work, and Politics: The Remarkable Partnership of Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot.” Theodore Roosevelt, Naturalist in the Arena. Edited by Char Miller and Clay S. Jenkinson. University of Nebraska Press, 2020. EBSCOhost.

National Park Service. “Theodore Roosevelt and the National Park System – Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. United States Department of the Interior, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/thrb/learn/historyculture/trandthenpsystem.htm.

Nicita, Antonio, and Matteo Rizzolli. “The Economics of Art Thefts: Too Much Screaming over Munch’s The Scream?” Economic Papers (Economic Society of Australia), vol. 28, no. 4, 2009, pp. 291–303, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-3441.2010.00045.x.

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. “Fact Sheet: America’s Presidents.” Smithsonian Institution, May 9, 2023. https://npg.si.edu/about-us/press-release/americas-presidents.

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. “Theodore Roosevelt.” Smithsonian Institution, September 13, 2019. https://npg.si.edu/learn/access-programs/verbal-description-tours/theodore-roosevelt.

Smithsonian Office of Protection Services. “Explore the Offices.” Smithsonian Institution, 2025. https://security.si.edu/explore-offices.

Smithsonian Office of Protection Services. “Office of Protection Services (OPS).” Smithsonian Institution, 2018. https://security.si.edu/.

United States. 96th Congress. “Public Law 96-487: Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act.” 94 Stat. 2371. December 2, 1980. https://www.nps.gov/locations/alaska/upload/ANILCA-Electronic-Version.PDF.

The White House. “Unleashing American Energy – the White House.” The White House, January 21, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/unleashing-american-energy/.

Voss, Frederick, and National Portrait Gallery. Portraits of the Presidents, the National Portrait Gallery. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2000.Ward, David C. “‘…For the People’: The Presidential Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery.” Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Smithsonian Institution, December 13, 2016. https://npg.si.edu/blog/people-presidential-portraits-national-portrait-gallery.