My scheme is simple, legitimate, and brilliant. I will be abusing the centuries-long used techniques of coin-minting to create exceedingly realistic fakes of the Shekels of Tyre (ancient Phoenician coin), and in doing so make a pretty sum while fooling both connoisseurs and experts of the numismatic trade.

The idea occurred to me when my husband was peripherally watching Pawn Stars, and a man with one of, “The coins used to pay Judas,” entered and earned a decent buyout. As I had encountered on Pawn Stars, the tourist appeal of Al Tyre Shekel comes from not its deep roots in metallurgy or numismatic history, but its titular appeal in the bible as the currency oft quoted by Jesus, “But so that we may not cause offence, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours.” (Matthew 17:24-27 NIV), and infamously used by Judas, “Then one of the 12, called Judas Iscariot, went unto the chief priests, and said unto them, ‘What will ye give me, and I will deliver him unto you?’ And they covenanted with him for 30 pieces of silver.” (Matthew 26:14-15 NIV) This popular appeal makes the Tyre al Shekel one of the most coveted collectible coins on the market, with price (dependent on quality and auction) ranging from $500 to up to $3,500, or even $5,000 USD. You can see the appeal for creating fakes, and there are a lot of them.

“Then one of the 12, called Judas Iscariot, went unto the chief priests, and said unto them, ‘What will ye give me, and I will deliver him unto you?’ And they covenanted with him for 30 pieces of silver.” (Matthew 26:14-15)

The Shekels of Tyre were struck during the fourth and fifth centuries B. C. in the city of ancient Phoenicia, a large trading central on the coastline well-known for its purple dyes extracted from Murex shells in what is now modern day Lebanon. There were large quantities of coins printed, but the most important ones were between the two centuries of 126/5 B.C and .A.D 65/66. Throughout this time there were two types of coinage in circulation: the Shekel and the Half Shekel, which were virtually the exact same except half the size, and were likely issued principally to pay the annual tax for the Jewish Temple, which all men above the age of 20 were required to pay. You can see one of the earliest issues of the shekel on the left and the latest of issues on the right below.

On the obverse side (the head of the coin) is a picture of the Laureate head of the mighty Melkart, the tutelary God of the Phoenician city-state who was often thought of as the Lord of Tyre. He is a Canaanite-deity with heavy associations to Heracles/Hercules of Greece and Rome, which you can see connection to on the coin–with the skin of a lion dressed around his neck. On the Reverse, an Eagle standing on a boat’s prow with a palm frond seen behind eagle, and the club of Melkart in the left field. (Cited from: https://www.cointalk.com/threads/what-happened-to-the-autonomous-tyrian-shekels.358869/) These coins were easily recognized as the most widely accepted coin in the Levant for nearly 200 years, likely because of their purity of silver and their consistent weight. However, despite their popularity, these coins’ design stirred quite a controversy, for the Israelites procuring this type of coinage meant that they were de facto violating two of their ten Jewish commandments dictated to them by Moses: forbidding the depiction of foreign deities and graven images. No, “self-respecting,” (Justin Robinson, Blood Money) Jew was lief to carry this coin in their day-to-day transactions. Nevertheless, “Since this was the only currency accepted by the Jewish religious leaders for the annual temple tax, it meant that the temple vault would have been filled with silver coins depicting a foreign god!” (Justin Robinson, Blood Money)

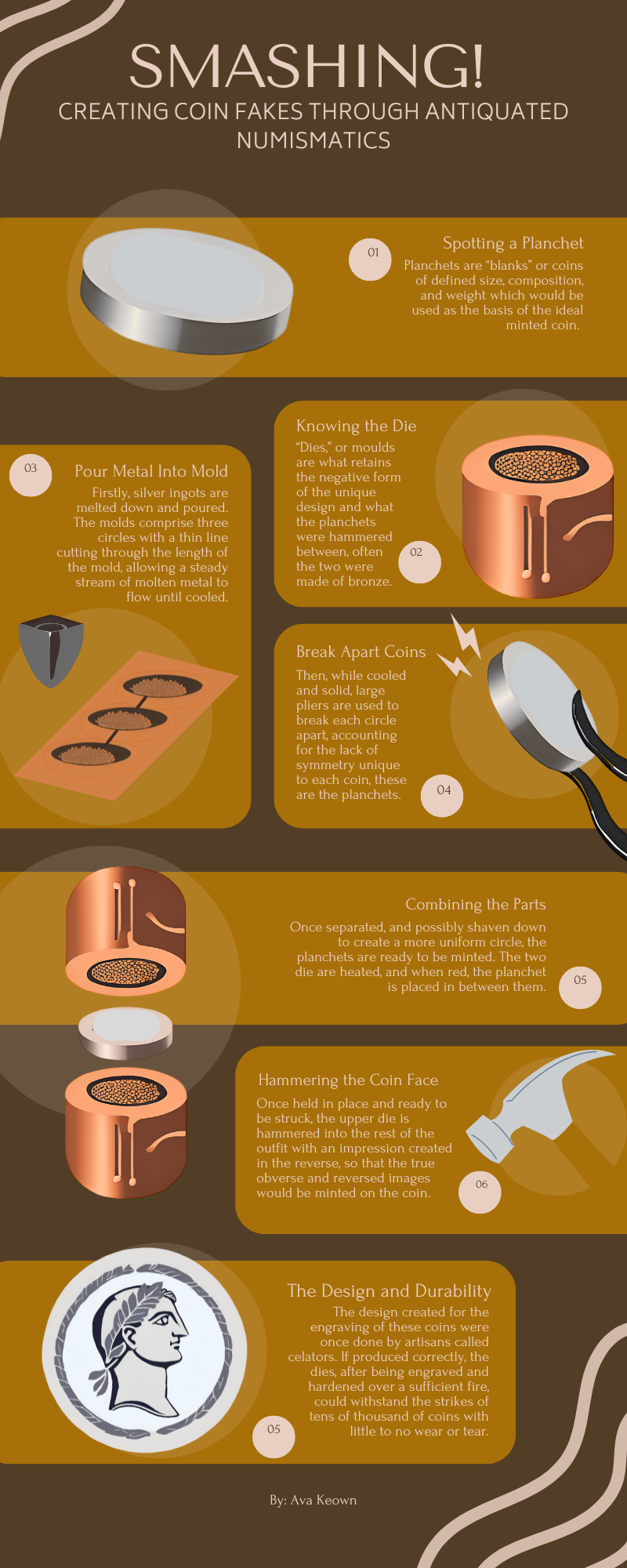

Fake Shekels of Tyre, as well as most other fraudulent coins, are created by use of hydraulic presses, or casting. Real coins, as described in the infographic at the bottom, were minted by the use of silver ingots being melted down and poured into molds. The molds would comprise three circles with a thin line cutting through the length of the mold, allowing a steady stream of molten metal to flow until cooled. Then, while cooled and still solid, large pliers would be used to literally break each circle apart from each other, accounting for the unsymmetrical imperfections unique to each ancient coin. Then, once separated and sometimes shaven down to create a more uniform circle, the coin would be reheated until scorching red, and then proceeded to be hammered by a giant hammer while placed between two die with an impression created in the reverse, so that upon striking, the true impression of the visage would be minted upon the coin.

Where the outcome of the different styles of minting lie is evident upon the metal’s reaction to the differing methods of applied pressure. With the process of the ancients’, a hammer suddenly striking the middle of the coin would create lines, stretching from the center outwards and sometimes even cracking through the edges of the coin, creating drastic and unique markers called “flow lines”. (See above.)

This, coupled with the imprecision of the strike of the hammer, created facets unique to each coin. A hydraulic press, however, creates exceedingly symmetrical coins with an even press, causing stress to the metal by forcing it to pool outwards and bubble at the edges. A difference not realized by the untrained eye, but to an experienced hand, is an immediate giveaway to the authenticity of a singular coin, regardless of patina or other forms of distress present in the item. Where my process and the process of forger’s differ is in the process of production; wherein forgers attempt to create minted coins by process of hydraulic press, I, on the other hand, intend to use the authentic methods of our metallurgical ancestors and use hammer-struck methods, thus making my product completely indistinguishable from appraised coins, and thusly rendering me a complete menace to the entire market.

“Despite depicting the head of a pagan god and a graven image, both of which were deeply objectionable to neighbouring Jews, the silver coin struck at Tyre became the only currency accepted by the Jewish religious authorities to pay the annual temple tax. This is because it was struck in the purest silver available in the region (about 95%) making it significantly more valuable than the Roman silver coins imported from the Far East that contained only about 80% silver.” (Robinson, Justin. “Blood Money – the Shekel of Tyre.”)

Here arises my first complication: the percentage of silver in the metal alloy. For the newly initiated, “Even silver that has been fully work-hardened, either by rolling or forging, gradually recrystallizes, even at room temperature. This greatly softens the metal, making it susceptible to scratching and marring. To maintain hardness, therefore, other metals are added to form alloys that are harder, stronger, and less prone to fatigue.” (Encyclopædia Britannica, “The Metal and Its Alloys.”) The Shekels of Tyre, having the highest concentration of pure silver in the region, is what made them so valuable. Recreating a similar alloy is important, as this is what can be measured by weight and sheen, and compared convincingly to authentic shekels. However, creating such an alloy would be difficult, as even, “Sterling silver contains 92.5 percent of silver and 7.5 percent of another metal, usually copper; i.e., it has a fineness of 925.” (Encyclopædia Britannica) While a lab analysis of my coin is unlikely, I am skeptical to see how the weight and metallurgy holds up under proper inspection. Robert Deutsch, an Israeli antiquities dealer, archaeologist, epigrapher, and numismatist, “Did a metallurgical test on 6 of these shekels and their purity averaged 96.16 %.” (Cited from: https://www.cointalk.com/threads/what-happened-to-the-autonomous-tyrian-shekels.358869/) However, seeing as he, “is known for being accused of six forgery charges of several biblical archaeological artifacts in 2004,” (The Associated Press, “Museums warned about Bible-era fakes”, 2004) and has been tied up in ongoing investigation and lawsuit since then, a minor discrepancy of weight in my coins should be fine.

While using sterling silver is expensive, it is far better than being sloppy, especially with such a large payout available. For my *hypothetical* scheme, I would be able to do it right here, in Flagstaff Arizona, on my property outside of town. Minting coins, with the hammering and roaring furnace and all, is a noisy business, so forging would be best attempted either deep in the noisy underbelly of urban-ism, such as by other industrial centers where you would be inconspicuous, or done far away from peering eyes– such as just off of I-40. Being in Flagstaff is also convenient, as buying sterling silver in bulk is available. At Thunderbird Supply Co., for instance (I don’t mean to incriminate them with my product placement), a quick glance sets sterling silver “clean scrap” as available for just under $40 an ounce. While that sum is hefty, remember that I will only be minting coins, only about an inch across, so not much metal is necessarily needed, especially since I will only be minting three at a time.

Patina or visual age is not a concern for me, as while cleaning a coin does lessen the value as it is considered “damage” to the coin, I would much rather tank the financial loss than dive into the foray of chemical aging, of which, from what I have seen, is exceptionally easy to notice the fraudulence of. Working with real silver also, while expensive, means that my product would become an exceptional forgery, instead of other poorer forgeries like those which use a process called “silvering plating.” This is when one takes a cheaper metal or alloy to mint, such as brass, and then covers said blank with a thin layer of silver melted on top, proceeding to then mint the blank afterwards. There is an astonishing amount of variety and creativity put to this process over the course of these past few millenniums, but that is the long and short of it.