I never intended to steal a painting like this one.

I have always said it would be too risky, too high-profile, too complicated, too likely to be caught. But when the payout is as extraordinary as this, and the mark is one of the most celebrated cultural icons of British history, how can a thief like me pass it up?

My name, not that you’ll find it on any national database (or international for that matter), is irrelevant. What matters here is the job. This is not your average snatch-and-grab, or a theft for the ransom, or even a heist connected to the mafia. This job falls under my specialty:

A commissioned theft, a precision operation. As romantic as it gets.

The client? A collector with pockets so deep and privacy so guarded she might as well be a ghost. Her desire? Joseph Mallord William Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, 1839. Oil on canvas, 90.7 by 121.6 centimeters of national pride, sitting quietly in the National Gallery in London, accession number NG524. Untouchable. Or so they thought.

The Meeting

Let me take you back to the first time I met with my client. She found me through the whisper network I worked diligently to build and continue to work tirelessly to maintain. Prior to this, I had stolen many smaller works from nameless galleries across the United States and Western Europe.

I tend to keep a low profile, avoid too much heat on or near my operations. I’ve never gone after big names, but I’m fast, clean, and professional. Above all: I get the job done without leaving a trace.

Slowly, word starts to spread in certain circles, in quiet conversations between those who are looking for help outside the bounds of law. That is where she heard of me, not by name, of course. Only by reputation. She contacted me through another client and flew me discreetly to Vienna to finally meet her face-to-face.

She explained to me her want, no, her need, to own this Turner painting. It wasn’t just a passing obsession. This was personal to her, borderline crazy (but who am I to judge). It was a matter of possession. Control. Legacy.

I was flattered. To be hunted down by a ghost collector with that kind of reach meant my name carried weight in places most thieves could only dream of. I protested at first, after all this job would be my most difficult one yet, and it might not be worth the risk.

However, it didn’t take long for her to pull me into the fantasy, and soon, it wasn’t just about the money, it was about stepping into the realm of myth.

The Obsession

As I began to plan the heist, I quickly understood her obsession. This is not just a painting, The Fighting Temeraire is a symbol of Britain’s naval past, considered to be a metaphor of the transition into the industrial era. The warships of the past becoming trivial with the introduction of steam power. The scene set against a blazing sunset, an allegory for the closing of this chapter in history.

In my research, I found William Rodner explained it perfectly: “a majestic eighteenth-century ship, rendered insignificant by the developments of the new century, set incongruously in the uncompromising environment of early nineteenth-century London.”

The cultural value of the painting is immense, but it is also a unique financial opportunity for a thief like me. Due to The Turner Bequest, nearly all of J.M.W.’s works are in the Tate or National Gallery collections, making any privately held Turner rare, and in the eyes of my client, priceless.

In deciding what my fee would be, I did my research. The record-breaking auction of Turner’s Rome, from Mount Aventine in 2014 led to the painting being sold for $47.4 million. Some estimate The Fighting Temeraire could surpass that figure due to its fame and completeness of provenance. My fee is typically 80% of the estimated price of any work. So, with The Fighting Temeraire, my fee became $40 million. A hefty sum to most, but for my client to achieve her dream, this was nothing, pocket change.

At this point in my career, the highest payout I had ever gotten for a job was $700,000. Stealing this Turner painting would be the biggest heist I had ever attempted, but for this extreme amount of money, I became dedicated to doing it, and doing it right.

The Plan

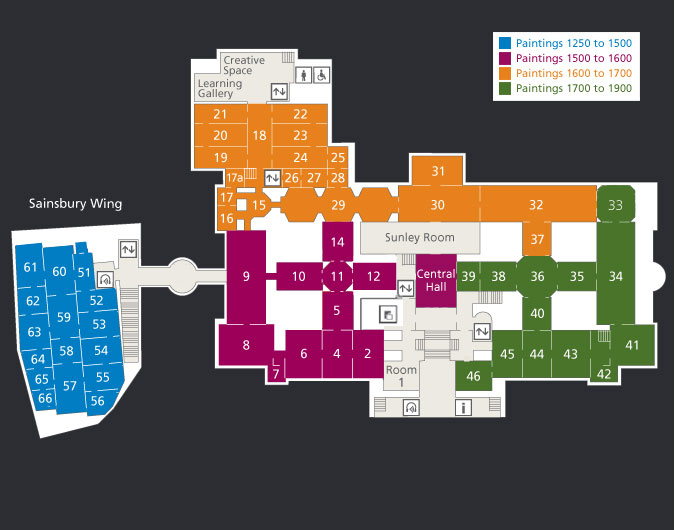

Along with The Fighting Temeraire, The National Gallery in London houses over 2,300 paintings, spanning from the 13th to the early 20th century. It is what one might call sacred ground.

Coincidentally, the museum is currently undergoing a massive redisplay and redesign, a once-in-a-generation overhaul which according to the museum, is meant to rethink how art is presented. This was the perfect opportunity, and as my mentor would say during my teenage years: even sanctuaries falter during construction.

Once I learned that this redesign was happening, my mind was spinning with the possibilities. Construction zones mean temporary walls, blind spots, contractors walking freely, and distracted security teams. Chaos doesn’t just create ghosts, it invites them.

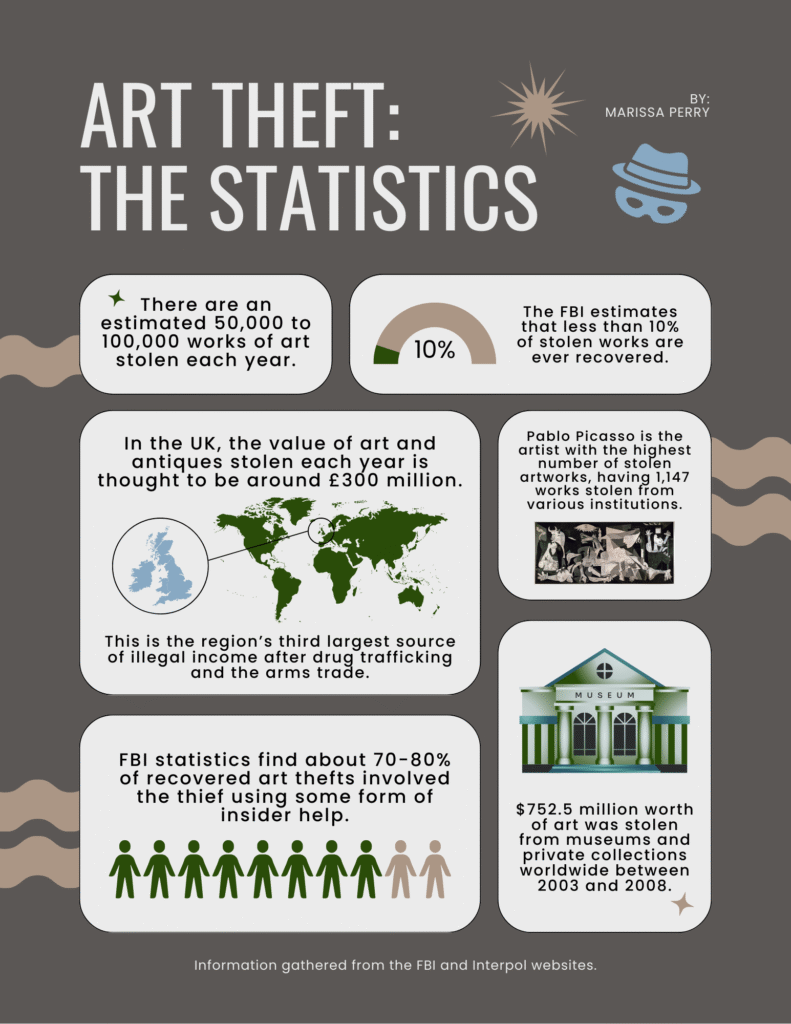

From my long career as a thief, I have learned to understand the statistics on art crime. One of the most important ones, to me at least, is the fact that FBI finds about 70-80% of solved art thefts involve inside help. So, I know that the closer I work with my own hired team, the better chance I have of getting what I am after.

In the months before the theft, I started to move my crew into position. I typically pull in only one of my three trusted specialists in these types of operations. But for a job as big as this one, I was in need of all three.

The first of my team to gain access to the museum was my tech specialist. Through our previous work together, and while doing research on the architectural firm working with the museum, we have learned that general contractors typically are not the ones doing alarm system work, in order to keep a kind of confidentiality. Due to this, we planned to have her posing as a specialized security consultant with the security firm that is working alongside the gallery’s redesign contractors.

Another member of my team was embedded as a courier working for an art shipping company, hired to move smaller works during renovation. Both have submitted and passed background checks under aliases we created years ago.

Our intel reveals that The Fighting Temeraire is currently on display on the second floor of the National Gallery, in Room 40, not far from the Sainsbury Wing, where most of the construction work is going on.

Through my tech specialist, we learned that the painting was planned to be taken off display temporarily for routine maintenance, and planned the heist for the day the painting was removed. It was to be placed in climate-controlled storage behind a keypad-entry room accessed only by select curators and security personnel.

This, ironically, made the job easier. It was to be out of sight, with less immediate oversight, all we had to do was get into the room.

The Heist

On the day of the heist, our first step was diversion. The third member of my team, a contractor working with the electrical engineers, triggered a false alarm on the other side of the gallery. The security team scrambled to investigate a potential glitch in the system. It was noisy and it was annoying, but more importantly, it pulled attention.

Next, my courier escorted a climate-controlled crate into the archive wing, citing scheduled pickup for conservation transfer. We had exact replicas of the paperwork and digital clearance needed, planted in the museum weeks prior.

My tech specialist, already in the system, looped the CCTV for that area. Cameras showed a quick second of static, then a time loop.

Less than five uninterrupted minutes. That’s all we needed.

The last step was extraction, that’s where I came in. I was dressed as a courier’s assistant, with my gloves on, earpiece in, and keycard ready.

The crate I brought in was empty. The one I left with carried The Fighting Temeraire. Wrapped carefully, protected from vibration, humidity, and judgment. Easy. As. Pie.

The Aftermath

I never keep the art I steal, that is rule number one. My client received the painting within 72 hours, routed through three cities and two decoy couriers. The payment was made to me through several offshore accounts, and I made sure that there was no digital trail.

My team was paid handsomely, $5 million each, leaving me to pocket a total of $25 million. My biggest score yet.

I’m not scared of being caught though, my team and client want this kept quiet as much as I do. My client simply wanted to possess what others cannot, and that level of hubris should be enough to keep my name out of it if she ever gets caught with the painting.

They say that theft feeds the ego as much as it does the markets. That’s what this is. My collector? She now owns the un-ownable and will soon forget who I am. And me? I got the challenge. The thrill. To beat the odds.

Of course, afterwards there was chaos. The British press lost their minds, and the museum went into total lockdown. But with no trace, no clear motive, and no ransom demand, they’ll be chasing shadows.

My collector will likely hang the painting in a subterranean vault, where only she and a select few will ever see it again. As for me, I disappeared for a while. The money is enough to set me up for life.

I travelled for a while, between my villa in Naples and a penthouse in New York. I thought about writing fiction under a pseudonym. But my mind always comes back to planning my next theft. Because once you pull off a heist like this, retirement gets… boring.

The Statistics

Key Works and Further Reading

Chappell, Duncan, and Saskia Hufnagel. Contemporary Perspectives on the Detection, Investigation and Prosecution of Art Crime: Australasian, European and North American Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing Group, 2014.

Chen, Frederick, and Rebecca Regan. “Arts and Craftiness: An Economic Analysis of Art Heists.” Journal of Cultural Economics 41, (2017): 283-307. Springer.

Michaud, Eric C. “Museum Security and the Thomas Crown Affair.” Journal of Physical Security 4, no. 1 (2010): 31–35. EBSCO.

Nairne, Sandy. Art Theft and the Case of the Stolen Turners. Reaktion Books, 2011.

Rodner, William S., and J.M.W. (Joseph Mallord William) Turner. J.M.W. Turner: Romantic Painter of the Industrial Revolution. University of California Press, 1997.