By Andrew Peters

I am not a thief…

But if I was this is how I would start my career.

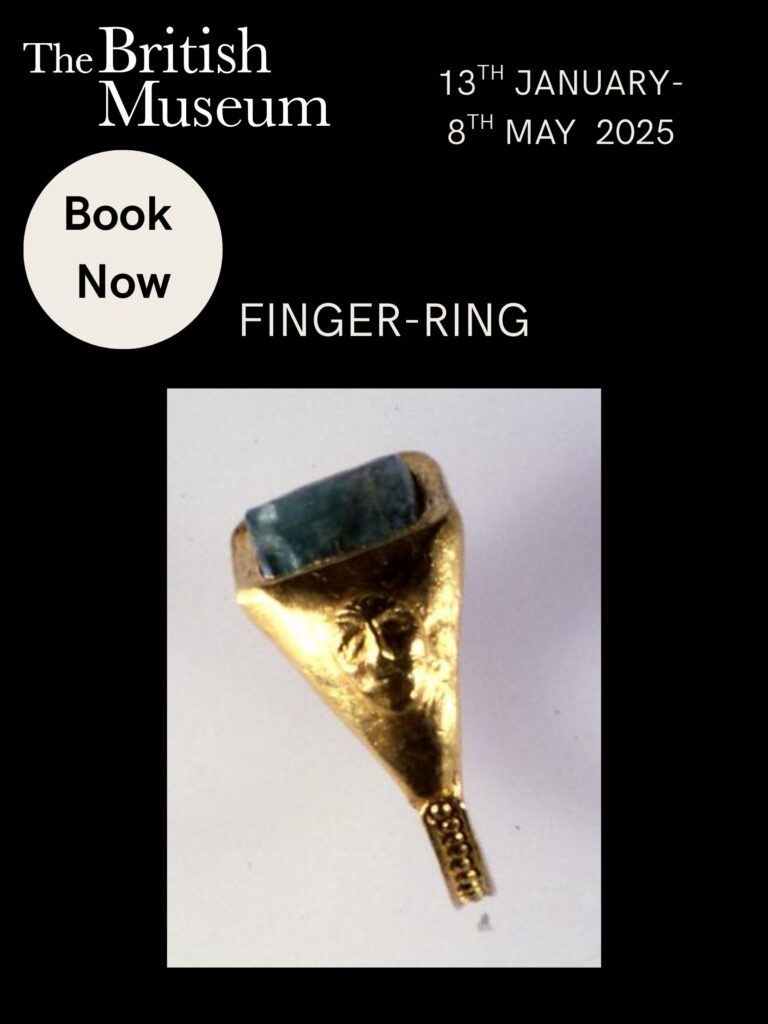

My target is one of the golden rings excavated from Thetford, Norfolk in 1979 that is currently housed at The British Museum, located at Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3DG.

Below is one of those twenty rings I intend to steal.

The ring I set my sights on is a gold band with a rope motif on the lower half and face masks on each side. The top has an emerald set in it. The Finger-Ring’s measurements are 17 millimeters (0.67 inches) in diameter and weighing 9.20 grams. It’s identified in the museum’s catalog as Finger-Ring (Museum number 1981,0201.9).

To steal it, I would

befriend a local security guard, get to know him for a while and then ask to be let in after-hours with the promise of beer and pizza. After infiltrating, I would sedate him with a chloroform rag and tie him up to ensure the alarms won’t get tripped immediately, I would take a hammer and chisel to break the glass to snatch the ring, this would naturally trigger the alarm. I would flee the scene and attempt to stow away on a cruise ship departing the UK. This imaginary successful theft of the Romano-British emerald finger-ring from The British Museum requires a meticulous understanding of historical art theft methods, I hope with this essay’s extensive look at historical art theft methods, museum security protocols, and the black-market art trade, a case can be made for this heist to possible for a single antique of immense cultural and financial value can be smuggled, altered, and stolen from even the most modern safeguards in a Museum.

This here is IndiGo ( Indi for short). He might not look it, but he has a respectable job as a security job at the British Museum. I plan to befriend in by just bumping into him at the trendy hipster bar down the street.

From there I will work diligently for months getting to know him, his friends, his family all in an attempt to wiggle my way into the museum.

After gaining Indi’s trust, I will smuggle in beer, pizza and maybe weed into the British Musem after hours. I suspect this will take about a one to two months of us doing this ritual. He won’t expect me to show up one night with a chloroform rag and a pair of handcuffs. I would then wrap the rag around Indi’s mouth and when his body goes limb from unconsciousness, I will cuff him to a lead pipe in the basement and make my way over to the Finger-Ring.

While its academic and

historical value is undeniable, the ring’s physical composition gold and emerald also makes it highly valuable in the underground market. The precedent for the dismemberment and resale of

stolen artifacts can be seen in the infamous practices of art thieves such as Giacomo Medici, who smuggled artifacts out of Italy, restored them, and sold them to international collectors

(Tsirogiannis, 2016).

Once freed from the setting, the emerald could be taken to a jeweler for appraisal and then sold to a private dealer or on the black market. This method would unfortunately destroy the ring’s historical integrity, but history has shown that thieves often prioritize profit over preservation. A notable example is the theft of a golden Dacian helmet from the Drents Museum in Assen, Netherlands where experts speculated that the thieves would melt the helmet down for its gold content (Reyes, 2025). This presents a similar dilemma while keeping it intact could allow for a more lucrative sale within the underground art trade, its raw materials provide an alternative avenue for liquidation. Similarly, Finger Ring along with the other treasures that were excavated by Arthur Brooks in 1979, all discovered to have a gold content ranging from 89% to 95% purity which highlights the allure of precious metals for illicit gain, even at the cost of cultural loss (Mitchels, 46).

The fate of the Finger Ring, in the context of this class paper, will be rather grim. Whatever past history the band could have illuminated to the future generations will be melted down for short sighted

plunder.

The British Museum will employ sophisticated security systems featuring CCTV

surveillance, motion detectors, reinforced glass display cases and security personnel stationed throughout the premises. To overcome these obstacles, I will execute a plan that minimizes direct confrontation and maximizes stealth a very similar tactic to how other famous works of art were stolen such as the 1911 Mona Lisa heist or the 1994 theft of The Scream (Durney & Proulx, 120). After all, As Berns notes, protective cases, designed to deter theft through reinforced glass and alarm systems often serve as delegated security actors, assuming the role of guards to prevent physical access to exhibits (Berns, 156). To gain access to the museum after hours, I will befriend a local security guard, persuading him with the promise of beer and pizza. Establishing rapport with a staff member allows me to exploit human error, which is often the weakest link in any security system and allows me to exploit human vulnerabilities much like phishing attacks in digital crimes (Grover, 14).

Museums rely on personnel vigilance as much as they do on technological defenses, and social engineering has proven effective in numerous heists throughout history. South African artist Jane Alexander’s “Security” installation, showcased at the 2009 Joburg Art Fair encircled a birdlike figure with razor wire and guards, probing how safety measures familiar in private life shape public encounters. Cobi Labuscagne, in “Crime, Art and Public Culture” (Labuscagne, 357-378).

I will wear gloves and a hairnet to minimize trace evidence, a precaution informed by the meticulous analysis of art theft investigations (Sloggett, 2015). I will employ a hammer and chisel to break the glass the ring. This transgressive approach touches on different sociologists like McAuliffe and Iveson on how society negotiates what is considered art versus crime, this plays with our traditional sensibilities of artistry ownership revealing the negotiability rather than impenetrability inherent in art (McAuliffe & Iveson, 130).

While this approach may trigger the alarm, speed will be my primary advantage. In many cases, the time it takes for security to respond to an alarm can be the critical window needed for escape.

I will stow away on a cruise ship departing the

UK. Historically, stowing away on cargo or passenger vessels has provided criminals with a means of escape, as maritime travel offers anonymity that is harder to achieve in an airport setting. Keshavarz highlights how smuggling exploits the material configurations of borders such as vehicles and infrastructure to facilitate illicit mobility, suggesting that ships, like trucks in his examples, can serve as tools to reconfigure escape routes (Keshavarz, 3).

This heist, even if imagined, I hope exposes some of the faults inherent in the security of the GLAM space particularly in museums.

All the advanced technology in the world cannot trump human failings. We must make sure that honest, professional, good employees need to be hired on in order to protect the rare antiques inside.

As for the Romano-British Ring, whether its fate was melted down is largely irrelevant. The money gained from any transaction will never replace the historical significance of the ring’s meaning in pre-Anglo-Saxon Britain.

Works Cited:

Berns, Steph. “Considering the Glass Case: Material Encounters between Museums, Visitors and

Religious Objects.” Journal of Material Culture, vol. 21, no. 2, 2016, pp. 153–68,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183515615896

Durney, Mark, and Blythe Proulx. “Art Crime: A Brief Introduction.” Crime, Law, and Social

Change, vol. 56, no. 2, 2011, pp. 115–32, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-011-9316-3.

Grover, Amit, et al. “The State of the Art in Identity Theft.” Advances In Computers, vol. 83,

Elsevier Science & Technology, 2011, pp. 1–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12

385510-7.00001-1

Keshavarz, Mahmoud. “Smuggling as a Material Critique of Borders.” Geopolitics, vol. 29, no.

4, 2024, pp. 1143–65, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2268528.

Labuscagne, Cobi. “CRIME, ART AND PUBLIC CULTURE.” Cultural Studies (London,

England), vol. 27, no. 3, 2013, pp. 357–78,

https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2013.769150.

McAuliffe, Cameron, and Kurt Iveson. “Art and Crime (and Other Things Besides … ):

Conceptualising Graffiti in the City.” Geography Compass, vol. 5, no. 3, 2011, pp. 128

43, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00414.x

Mitchels, Mark. “The Thetford Treasure.” Treasure Hoards of East Anglia and Their Discovery,

Countryside Books, 2013.

Reyes, Ronny. “Experts Fear Thieves Will Melt 2,400-Year-Old Golden Helmet Stolen from

Dutch Museum: ‘It Is Simply Unsellable.’” New York Post, New York Post, 27 Jan.

2025, nypost.com/2025/01/27/world-news/experts-fear-thieves-will-melt-2400-year-old

golden-helmet-stolen-from-dutch-museum/.

Sloggett, Robyn. “Art Crime: Fraud and Forensics.” Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation,

The University of Melbourne, 2014.

Tsirogiannis, Christos. “False Closure? Known Unknowns in Repatriated Antiquities Cases.”

International Journal of Cultural Property, vol. 23, no. 4, 2016, pp. 407–31,

https://doi.org/10.1017/S094073911600028X