Never, in my exceptionally lengthy and lonesome career, have I been called upon for anything, much less for consultation. Yet, as luck would have it, someone has managed to track me down and ask me for advice. Unheard of. “AJ,” they wrote. “How would someone with your experience go about forging something like, say, the Gutenberg Bible?” Well, anonymous writer, if I absolutely had to, I would begin by saying that the circumstances of the situation laid out here are unrelated to me and my career, and if, by a second miracle, you manage to track me down again, none of the information contained here is an admission to any possible criminal activity of which I am, have been, or may be suspected. Then I would begin researching the object itself.

The History

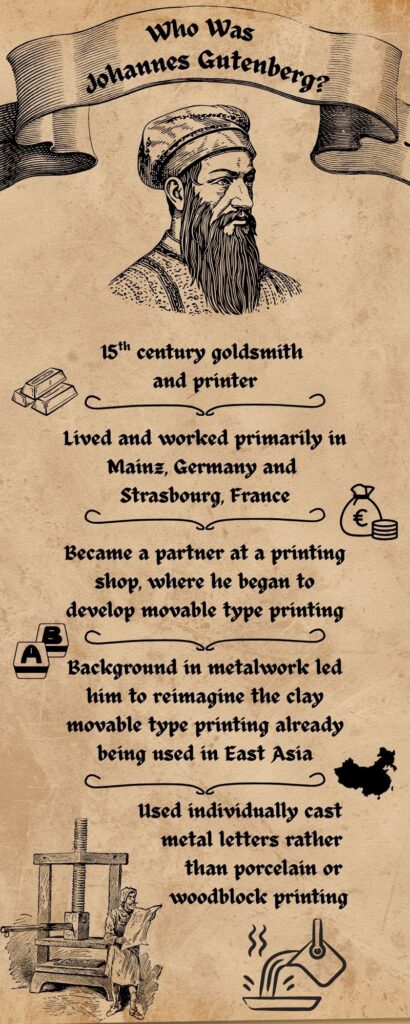

The first thing you have to know about a piece like the Gutenberg Bible is its history, especially when forging it. This Bible was the first major bound text printed in Europe using movable type printing, which was pioneered by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century. Between 150 and 200 copies were printed, the majority on paper and the rest on vellum. This edition contained the Vulgate, which is made up of a Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible and the Greek New Testament. All of this information will help you in your forging process.

To forge a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, or even just a fragment of one, would be much easier than attempting the heist of one from a museum or library because most of the possible copies are unaccounted for.

Nearly every complete or near-complete copy of the Bible is accounted for, housed in some impenetrable glass case in a museum or library. However, because there are only about 50 substantial copies that we know of, that means the rest have been scattered across the globe over the last 500 years in fragments that are much harder to track.

The Value

Yes, a complete original copy of the Gutenberg Bible is worth a lot, and attempting to steal or forge a full bound edition would be extremely high risk, high reward, but fragments of the book also have a very high value attached to them, and are much easier to forge or acquire. An auction house once estimated the value of eight consecutive pages of a copy of the Gutenberg Bible to be around $100,000 apiece, for a total value of nearly $800,000 for the eight pages. Don’t be stupid and try to forge a complete copy. A mere fraction of the book would set you up for a good long while.

The Medium

The base of your forgery, literally, is the medium you use. For the Gutenberg Bible, I would opt for paper as my base, not vellum, because there were fewer copies printed on vellum. This would have to be paper from the same time period in order to pass any radiocarbon dating that may be done for authentication. Oftentimes, fragments and leaves of existing copies of the Gutenberg Bible were taken and reused to bind other books in the 15th and 16th centuries, being used as exterior binding, endpapers, or spine reinforcement. These pieces of the Bible are too fragmented and could not be removed and sold themselves, but it would be a smart option to get your base paper from a book that might have used these pieces as binder’s waste, such as a later version of the Bible, also printed by Gutenberg.

The composition and application of the ink is probably the most complex aspect of this whole process. Extensive research has been done into the chemical ink composition of some copies of this Bible, including the King George III copy, which I’m using as a point of reference. The ink palette used to print this specific copy was determined to be made up of applied gold leaf, and eight different pigments, which are as follows:

- Azurite (a bright blue mineral, often with a green tint)

- Calcite (basic chalk)

- Cinnabar (a deep red mineral composed of mercury sulfide)

- Malachite (a vibrant green copper carbonate)

- Lead-based white

- Lead-based yellow

- Carbon black (likely wood or bone ash)

- Organic-based red (likely a crushed-up fruit or insect)

Because the bases of the black and red ink are organic (as opposed to inorganic minerals) they are much easier to carbon date. The age of these materials would make or break an authentication, and finding the correct pigment at the correct age will be difficult. Just warning you.

The Press

The next hurdle, once you have the right paper and ink, would be the press itself. Because these bibles were mass produced on the Gutenberg Press, the skill in reproduction would come from how well you can replicate the machine. The multi-step process to craft each letter was tedious, but not complicated. The first step would be to carve the letter in relief on the end of what is known as a steel punch, reversing it so it is carved backwards. Doubled or linked letters such as ‘ff’ or ‘æ’ were originally carved onto one punch for a cleaner finish, and that should be replicated here. The carved steel punch would then be hammered into a piece of soft copper, leaving an impression of the letter–in its correct orientation–in the metal. The impressed copper would then go into a mold, and molten metal would be poured into it. An alloy with a low melting temperature and a rapid cooling time was chosen, consisting of lead, antimony, and tin. This mold would produce a relief stamp of the letter on the end of a metal block to be inserted into the printing press when needed. All of these metals–steel, copper, lead, antimony, and tin–would be essential to the reproduction process, covering your bases if an authenticator were to look for flecks of metal from the press embedded in the ink.

The Printing

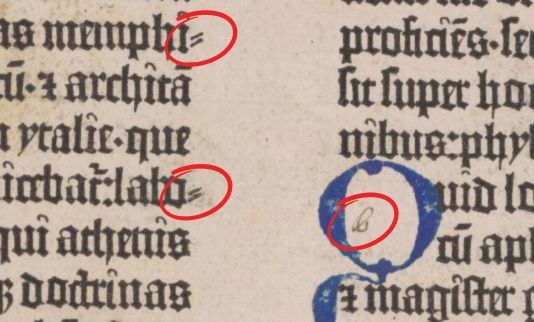

In addition to the metal type pieces, differences in the printing of the letters would be necessary to replicate — though, they’ll probably occur naturally. Before being pressed to the paper, each letter was hand-inked, meaning ink was applied manually to the stamps. This resulted in a nonuniform amount of ink applied each time. If a letter received more or less ink than a previous printing, it would appear darker or fainter on the page. The letter ‘i’ is particularly sensitive to this type of variation because it is very thin, and the inclusion of the point on a lowercase ‘i’ allows for it to smear, splotch, or not even print at all. If you replicate the printing process accurately, the forgery should have these same discrepancies.

The final element of the printing to account for is the compositor’s marks on some copies of the Gutenberg Bible. A compositor’s mark, also known as a catchword or typesetter, is a printed or scratched-in mark used to aid a compositor or binder in his work and ensure the copies are uniform, even if printed in different studios. These marks vary throughout copies of the Gutenberg Bible, and the inclusion or omission of one would differentiate clearly between one copy or another, so depending on the copy you are referencing, careful research into its compositor’s marks would be essential.

The finishing touch on this forgery would be aging it, or making sure the ink looks old and settled rather than fresh. Even though the materials themselves should already be old, exposing the forged pages to heat, light, or other elements would speed up the chemical process of aging, and give the ink realistic effects like fading and cracking. Once this step is complete, the forgery would be ready for sale.

The Sell

When attempting to sell a forgery like this, it must either have a fabricated paper trail, or no paper trail at all. By this, I mean I could not say I bought it from another seller, inherited it in a relative’s will, or any other story that would have receipts. Provenance of this kind is too easy to track. Instead, acting clueless might be smarter. “My uncle had this in a box of other papers in storage, I thought it was junk.” Or, “Someone pawned it off on me. It’s been so long now, I don’t remember who…” Both stories that could work, however flimsy. If I sold through a third party, this part is not even necessarily my problem. Plus, a third-party seller is–to be clear, hypothetically–an easy scapegoat for any criminal investigations that might get thrown my way. Now, any buyer willing to lay down $100,000 for one page of this Bible would know their stuff, and they would be serious about authentication. If you have correctly and thoroughly carried out the steps I explained before, there should be few, if any, snags with this process. If you got lucky on this sale and ended up with a more amateur buyer, you might be able to fool them by bringing my own authenticator who would be willing to fudge the results, and if they’re really new, a faked certificate of authenticity might be all you need to be successful.

A hypothetical forgery like this one would be relatively easy for a skilled forger with the team and resources to accomplish it, and the piece is right in the middle of rare and high-profile, which would ensure a high asking price with little to no turning heads. If you have any questions about the information contained in this letter, or would like to inquire about another art-related subject, don’t. You should not have been able to get ahold of me in the first place. After writing this, I will burn the pen I used, pick another fake name, spit at a map, and move to wherever it lands. I wish you luck in your endeavors.

AJL signing off.

Bibliography

Arnau, Frank. The Art of the Faker: Three Thousand Years of Deception. Translated by J. Maxwell Brownjohn, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1961.

Christie’s. Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts Including Americana. London: Christie’s, 2021. Auction Catalog.

Goldman, John J. “Gutenberg Bible Is Sold for Record $4.9 Million.” Los Angeles Times, 23 Oct. 1987, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-10-23-mn-10733 -story.html. Accessed 5 April 2025.

Johannes Gutenberg. Gutenberg-Fust Bible. 1455. Inc.1.A.1.1[3761.1-2]. The Polonsky Foundation Treasures of the Library Collection. University of Cambridge Digital Library, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/ view/PR-INC-00001-A-00001-00001-03761/9. Accessed 5 April 2025.

Mari Agata and Teru Agata. “Statistical Analysis of the Gutenberg 42-Line Bible Types: Special Focus on Letters with a Suspension Stroke.” Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 115, no. 2, 2021, pp. 167-83.

Mayumi Ikeda. “Two Gutenberg Bibles Used as Compositor’s Exemplars.” Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 106, no. 3, 2012, pp. 357-72.

Olmert, Michael. The Smithsonian Book of Books. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Books, 1992.

Sotheby’s New York. Fine Books and Manuscripts, Including Americana. New York: Sotheby’s, 2015. Auction Catalog.

Tracy D. Chaplin, et al. “The Gutenberg Bibles: Analysis of the Illuminations and Inks Using Raman Spectroscopy.” Analytical Chemistry, vol. 77, no. 11, 2005, pp. 3611-22.

White, Eric Marshall. “The Gutenberg Bibles That Survive as Binder’s Waste.” Conference Organized by the IFLA Rare Books and Manuscripts Section Munich, 19-21 August 2009, edited by Marcia Reed and Bettina Wagner, IFLA Publications, 2010.