TikTok user @ActuallyKindaComplete is not really an art historian. @ActuallyKindaComplete doesn’t have a doctorate in anything or a mysteriously wealthy family member. The creator does not have much of a pedigree to speak of, let alone create a TikTok art education account with, but the creator didn’t let their lack of credentials stop them from successfully marketing an account with over 600,000 followers—or raking in the profits. In February 2024, @ActuallyKindaComplete, whose civilian name is the unassuming Meredith Kelley, entered the ranks of Caroline Calloway and Anna Delvey in the craft of social media scamming, garnering criticism from art historians, economists, and angry art super-fans.

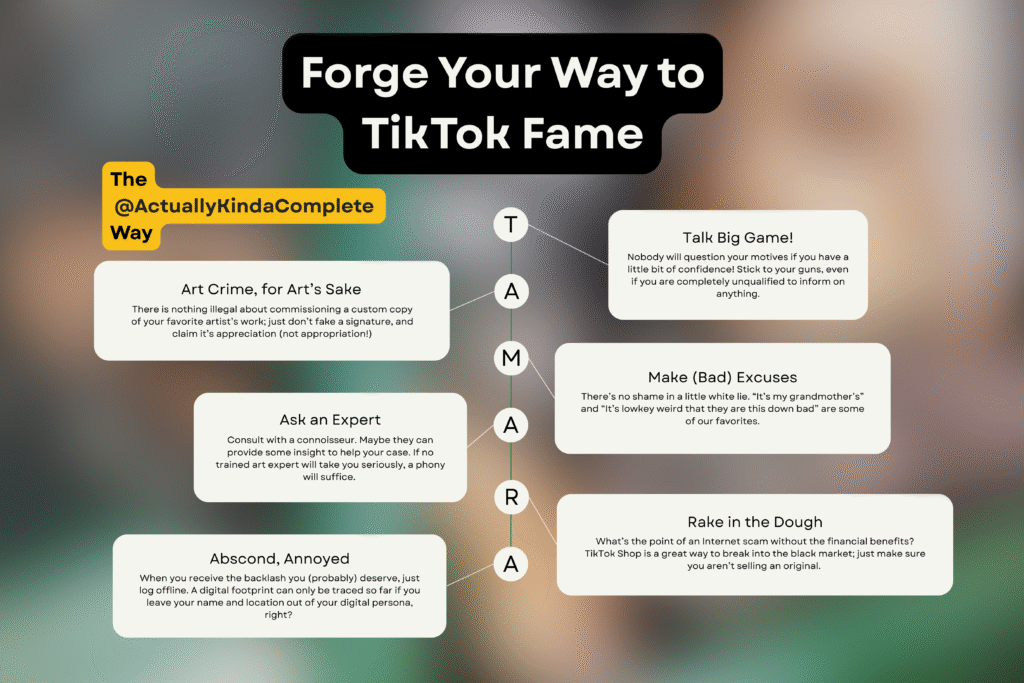

Sitting down with @ActuallyKindaComplete is like meeting a distant relative; Kelley will tell you everything about herself—much of which you already know—but each new piece of information only affirms your distance. For instance, she will be the first to admit that the scheme was simple: she paid one artist to create a forgery of a famed Tamara de Lempicka masterpiece and an actor to falsely attribute it to the artist. Add in the convenient, invisible paper trail of the TikTok Shop and the culpability of the Sotheby’s auction house conglomerate, and any internet scammer worth their salt would agree that Kelley was merely taking advantage of an already broken system of art commerce.

“I was bored…”

Kelley first launched her TikTok page in 2020, posting educational videos in major museum institutions and historical houses. Her fifteen- to thirty-second short films typically included simplistic choreography to trending TikTok music with relevant song lyrics or the creator lip-syncing to memetic audio, with additional close-up footage highlighting details of the art. Many videos on her page were companion pieces to these musical films, in which Kelley, who introduced herself as “your friendly art non-expert,” explained aspects of the art’s period, style, techniques, and creator by creating her own plot line for each work’s subjects. In the videos, Kelley’s delivery of this Wikipedia-level knowledge through fantastical storytelling was breezy and confident, providing an air of knowledgeable nonchalance with a thick Staten Island accent.

“I really like old houses and old art,” Kelley said. “TikTok is great for people like that. And to be honest, I never thought people would think I’m an expert in anything.” Kelley went to the University of Connecticut to study social work before quitting in 2022 to focus on her TikTok page. “And you know I never pretended to be an expert; I just wanted to tell stories. It was a great job to have, and even better to run my own business.”

@ActuallyKindaComplete is not the first art fanatic to strike while the TikTok iron is hot. Museums and history teachers alike have jumped on the platform as a method for discoverability and art education. Legacy art institutions like the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy have made use of TikTok to share and interpret prominent works of art and generate engaged visitorship from younger audiences, creating videos like Kelley’s by utilizing popular music, dances, and creators to display collections. Similarly, institutions will create long-form content aimed at detailing the work’s historical contexts, adopting a disquietingly serious tone that rarely integrates well with the vertical-scrolling format of the TikTok interface and user culture. Kelley’s blending of contemporary audio and linguistics with accurate, albeit simplistic, explanations of art and its historical contexts served as this necessary alternative for institution-sponsored art education, providing viewers with knowledge and Kelley with over twenty million views on her @ActuallyKindaComplete page.

Kelley learned much about art history from her page, too: “I never knew about movements, techniques, and styles. There were so many other art history creators on TikTok that I watched and who commented on my stuff. It was like being in this big community where everyone was trying to learn and share and entertain. I had the money to go to galleries all over the U.S. and see art I never would have dreamed of seeing. And I got to meet and platform artists.”

The Perfect Storm

The art community on TikTok has been especially active since the 2020 coronavirus pandemic’s lockdowns, when creators like Kelley began sharing creating and sharing new content to entertain audiences and grow their businesses during the global shutdown. This increase in the availability of art on the market intersected with the entry of Millennial-Gen Z “cuspers” to the collecting industry, creating a perfect environment for online artists to build community and sell their works. Indeed, Art Basel’s 2024 survey of art buyers found that “almost a third of respondents had made a purchase directly from an artist in the first half of 2024… 60% of those having purchased directly from an artist [did] so through Instagram in 2024”. While these figures do not account for the discovery capabilities presented by short-form video content like TikTok, these data from the year of @ActuallyKindaComplete’s peak in fame suggest that the internet was right for Kelley’s pivot from merely discussing art to selling it.

Furthermore, @ActuallyKindaComplete was distinctly identified as a home for feminist art history, with Kelley modifying her signature sign-on to “Your friendly feminist art non-expert” in early 2023. This self-identification and new focus on female artists were genuine on Kelley’s part: “I was so bored of talking about the Old Masters. I started out talking about the Old Masters and the Dutch guys and the Renaissance men and I was over it.” Creative expressions by female artists make up for a sizable portion of TikTok’s art community, with creators publishing their own art under the tag #feministart. Female artists and TikTok creators, whether they outwardly identify as feminist, are often encouraged to use #feministart or #feministartist, spurring immense debate over the meaning of praxis on an Internet fighting for gender equality. Kelley was eager to add to this dialogue, advocating for other artists on her page by sharing the works of other TikTok creators and discussing female-led movements for equity in art, despite never directly participating in art social circles. “When I found and got to know female artists on the app,” Kelley said, “I looked more into historical female artists and created more content about their paintings, which people really loved—and I loved. I loved Kahlo and Cassatt and Augusta Savage. And I adored Tamara de Lempicka’s nudes.”

“…And I liked her work.”

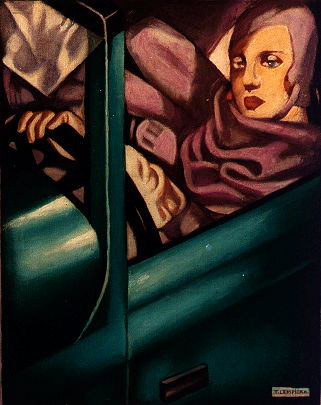

In January 2024, a very excited @ActuallyKindaComplete posted a video featuring a roughly 16 x 12 inch paining strongly resembling Tamara de Lempicka’s My Portrait (B.115) from 1929. Though she “doesn’t know nearly enough about Lempicka or technical things about art,” Kelley was thrilled, telling her followers the simplest of trivial lies: “My grandmother had it and didn’t really know what to do with it. I don’t know if it’s real, but I’m happy to have it.”

The reality was much more interesting: as a gift for surpassing 500,000 TikTok followers, Kelley purchased a Tamara de Lempicka of her own, commissioning a Vietnamese art studio to duplicate My Portrait. Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City is historically a hotbed of art reproduction, with international buyers flocking to galleries and dealers to order their own masterpieces. In a 2001 New York Times expose of the practice, one boutique, which then employed seven artists in the creation of high-quality reproductions, claimed that the shop can maintain 90 percent accuracy across all replicas. Crucially, these works can easily clear customs and border control but are rarely integrated into the art market at large. Adding to the convenience of this scheme, Tamara de Lempicka, born in Warsaw in 1898, created replicas of her own famous works during the last years of her life. Between 1974 and 1979, Lempicka painted new versions of her favorite pieces to give to friends and supplement her waning finances, including copies of Wisdom (B.507), Saint Anthony (B.518), and an incomplete La Belle Rafaëla (B.517). Besides the imprecision of the artist’s aged hand, these replicas are characterized by a distinct lavender hue, attributed to Lempicka’s failing eyesight and dissatisfaction with the quality of her pigments. Lempicka achieved the relative accuracy of her reproductions by tracing out her original paintings with pencil carbon paper, which she then transferred to new canvas and re-painted in her shakier hand. These practices and common visual characteristics were then replicated by the Vietnamese artists commissioned by Kelley, who created a piece strongly resembling a cooler-toned Self-Portrait III (B.514), Tamara de Lempicka’s third image of herself coolly speeding along in a sportscar.

Shock and Awe

The varied reactions to @ActuallyKindaComplete’s revelation of the “Lempicka-alike” were swift and severe, with legacy news outlets and Kelley’s own digital peers debating the resemblance between Lempicka’s reproductions and Kelley’s painting.

In early February 2024, the TikTok user publicized an email addressed to her and her “grandmother” from Sotheby’s auction house, offering to pay for provenance research, scientific testing, and a connoisseur’s appraisal of the piece’s authenticity through an aesthetic analysis of the work compared to other paintings in Tamara de Lempicka’s oeuvre in the years leading up to her death in 1980. Besides containing a rare offer to authenticate, Sotheby’s also propositioned Kelley to ensure a faster sale by utilizing Sotheby’s partnership with the eBay shopping platform. Sotheby’s has hosted live auctions and online-only auctions on eBay’s website since 2014. Despite this long-running partnership, both auction companies have failed to reach these lofty goals for online art and antiquities commerce, suggesting that the sale of Kelley’s missing Lempicka painting would be used as a tool to reinvigorate this dormant corporate campaign.

Nonetheless, Kelley declined this offer to perform basic identification processes. “It was a weird time,” Kelley later admitted, “and I handled it really badly.” By doubling down to the point of fraud?

“I think it was definitely fraudulent, but my followers believed me at first. People who are interested in art have a commitment to authenticity, and so do TikTok viewers. It’s very parasocial and very critical.”

In a Calloway-lite rendition of doubling down on her false claims, Kelley argued that she could not get the piece authenticated due to her lack of ownership of the painting; her grandmother was still alive, did not understand the internet, and did not want to have the work tested for authenticity by an outside source. To quell viewers’ suspicions of fraud, she called into question the very nature of the art market, writing in one expansive video caption:

I’m unsure how to make the issue of ownership clearer to you guys: I don’t own the painting and I have no provenance or bill of sale saying how my Grandma got the painting. She didn’t know Tamara de Lempicka, nobody in our family does. I’ve done the best that I can to shut down the media buzz about this, as it is the last thing that I or my Grandma want, but I really don’t know how to make all of this stop so I can just start making the content I love again. I don’t want to stop making TikToks but I’m also so anxious about this whole thing and dont [sic] know how to move forward [broken heart emoji]

I rejected the Sothebys [sic] offer because of this ownership problem, but also because I don’t want to be in the art market. I enjoy looking at art, but I am not qualified to be in the art market. Also, I think it’s lowkey weird that they are this down bad for authenticating a random painting from TikTok, but that’s a whole other thing I should I probably talk to a lawyer about first.

Kelley’s reflection on that statement today? “I didn’t even know how to get a lawyer.”

However, she did know how to locate an actor-friend to pretend to be a connoisseur of Art Deco painting, whom she paid to claim on video that the painting looked a whole lot like a Tamara de Lempicka. Still, neither she nor her still-anonymous art expert of an actor-friend claimed that the painting was authentic. “Nobody in the art history scene really believed that the painting was real, and most of my followers accepted that I wasn’t claiming it was,” Kelley argued. “But then all of this money got involved, which was so hard to turn down because I wasn’t taking any of it seriously to begin with.”

Icarus

In March of 2024, Kelley announced her intention to sell prints of the faux-Lempicka without making attempts to authenticate the work on its aesthetic or scientific merits as well as its provenance. The prints, which @ActuallyKindaComplete sold for the accessible price of fifteen dollars each via TikTok’s in-app shopping platform, reportedly made Kelley over $100,000, which she promptly donated to rural women’s shelters.

Upon the news of Kelley’s selling unauthorized prints of the unauthenticated work, Tamara de Lempicka’s estate quickly issued a statement decrying the painting’s authenticity, calling Kelley’s peddling of the forged artwork “a malicious betrayal to art historians and collectors around the world, as well as to Tamara’s well-earned and lovingly-protected legacy. This bid for profit and fame is not worth further attention or arbitration.”

@ActuallyKindaComplete then responded in a flippant video, soundtracked by Bhad Bhabie’s “Hi Bich”:

“If I wanted money or fame, I would’ve put my real name on the internet from the get-go, immediately commissioned and posted the painting, then sold it the second Sotheby’s gave me the chance. But I didn’t. If anyone remembers this, it will be as internet gossip, not as a major problem between an auction house and an artists’ estate.”

“This wasn’t my plan.”

Meredith Kelley was incredibly forthcoming throughout our interviews, going so far as to admit, “I don’t even listen to Bhad Bhabie. I just thought it was a funny song for a funny situation. This wasn’t my plan. Nobody plans for this stuff.” I pointed out that Kelley volunteered the false information regarding where she acquired the painting, to which she responded simply, “I don’t know why I said that. Looking back on it now, I was stressed and bored and wasn’t taking any of it seriously because there were no lawsuits and the charities were indifferent to the whole thing. I know how irresponsible that sounds, but I also know for a fact that there are a lot of other people out there committing worse acts of art forgery who will never get this sort of scrutiny.”

Once again, Kelley makes a good point. Art crime is an industry worth billions of dollars, ranging from philanthropic tax evasion to theft and, in Kelley’s case, forgery. Throughout our interactions and her public statements on the matter, Kelley is adamant that the sale of the Lempicka-alike prints had nothing to do with laundering illicit finances by manipulating the volatility of the art market or boosting her public profile, two possible benefits of engaging in white-collar art crime. Still, her permanent departure from the TikTok app, and the subsequent willful deletion of all content from her page, suggests some sort of guilt for what she did.

Her response?

“I was bored then, but I’m even more grateful to be boring now.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.