Provenance and selling

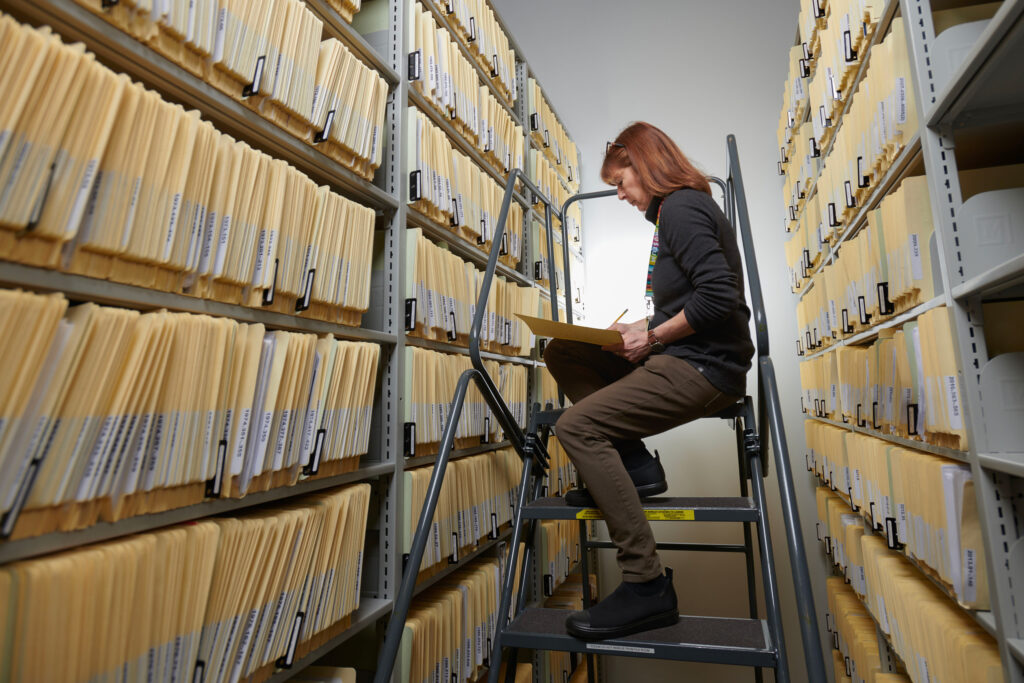

The last thing your painting needs is some history, otherwise known as provenance, the third method of authentication. Buyers and sellers examine the provenance of an artwork to ensure it has a clean history that connects all the way back to the artist. As a beginner forger, I consistently sold my forgeries alongside other paintings with official authentication certificates and transaction receipts. I never wanted my forgeries to draw too much attention, so having other paintings as buffers was important. Then, by altering the original documents, I could include my forgery in the receipts of the other paintings and replicate their authentication certificates to create my own.

The most valuable thing I have learned through forging is that all dealers are corrupt. When dealers have the potential to profit, they have very few incentives to reveal any information that may diminish the title and lower the value, thus making them the safest place to sell your forgeries. I always bring my paintings to a dealer with the story that they were part of a family member’s collection who always claimed they were original Courbet’s. The worst that can happen is that they were wrong, saving you from any possible legal trouble.

Bibliography

Carlyle, Leslie. “Authenticity And Adulteration: What Materials Were 19th Century Artists Really Using?”. The Conservator, num. 17, 1993, pp. 56-60. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leslie-Carlyle/publication/233276208_Authenticity_and_adulteration_What_materials_were_19th_century_artists_really_using/links/586c2e0808ae6eb871bb7259/Authenticity-and-adulteration-What-materials-were-19th-century-artists-really-using.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar. 2025.

Colombini, Maria Perla, et al. Analytical Chemistry for the Study of Paintings and the Detection of Forgeries. Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 2022.

Day, Gregory. “Explaining the Art Market’s Thefts, Frauds, and Forgeries (And Why the Art Market Does Not Seem to Care).” Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law, vol. 16, no. 3, Apr. 2014, pp. 457–95. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=30819cb9-35cf-3ca9-b48d-27788e19dcb6. Accessed 7 Mar. 2025.

Desbuissons, Frédérique. “Courbet’s Materialism.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 31, no. 2, 2008, pp. 251–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20108023. Accessed 7 Mar. 2025.

Gerstenblith, Patty. “Provenances: Real, Fake, and Questionable.” International Journal of Cultural Property, vol. 26, no. 3, Aug. 2019, pp. 285–304, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0940739119000171. Accessed 5 Apr. 2025.

Hebborn, Eric. The Art Forger’s Handbook. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998.

Morton, Mary G, et al. Courbet and the Modern Landscape. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

Payne, John. Framing the Nineteenth Century : Picture Frames 1837-1935. Victoria, Australia, Images Publishing Group, 2007.

Townsend, Joyce H. “Thermomicroscopy Applied to Painting Materials from the Late 18th and 19th Centuries.” Thermochimica Acta, vol. 365, no. 1-2, 4 Dec. 2000, pp. 79–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6031(00)00615-8. Accessed 5 Apr. 2025.

Wagner, Anne M. “COURBET’S LANDSCAPES AND THEIR MARKET.” Art History 4.4 (1981):410-431.https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/oxford-university-press/courbet-s-landscapes-and-their-market-VebIcjx20F?# Accessed 7 Mar. 2025.“Wildenstein Plattner Institute –

C.R_Gustave_Courbet_Tome_I_Wildenstein_Institute.” Publitas.com, 2025, view.publitas.com/wildenstein-plattner-institute-ol46yv9z6qv6/c-r_gustave_courbet_tome_i_wildenstein_institute/page/306-307. Accessed 5 Apr. 2025.