“Anybody can get the goods. The hard part’s getting away.”

Heist, 2015

Copy

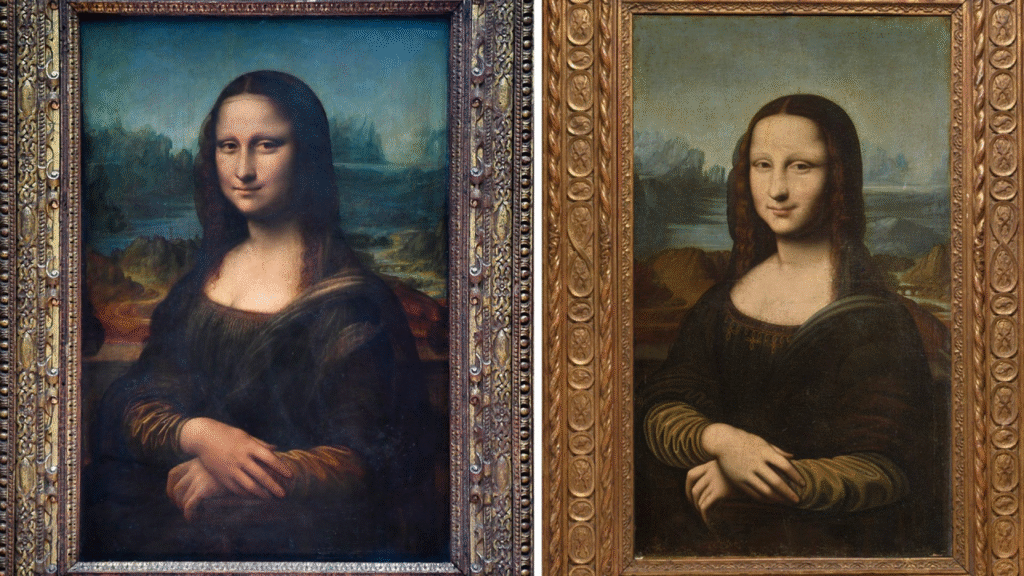

Scholar Noah Charney defines a copy as a “direct replica of a pre-existing work, or an artwork created in the style of a particular artist” (Charney 2016, 34). The intention of the creator differentiates a copy from either a fake or forgery. When creating a copy, the artist does not claim the work is an original.

In this instance, the creator is honest that the work is a copy and does not have the intent to deceive the audience. It is not illegal to create and sell copies of works of art since the artist is clear that the work is a reprint or representation of the original.

Copies and prints of famous works of art are common, such as prints of the well-known painting The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh, available in the shop at the Museum of Modern Art for $24.95. The description of the listing describes the print reads “a reproduction of The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, one of the most popular paintings in MoMA’s collection” (MoMA Design Store).

Fake

In contrast to copies, fakes are a type of art crime. Charney defines fakes as “work[s] of art, antique[s], or collectible[s] that [have] been tampered with for the purposes of fraud” (Charney2016, 34). These are original works which may have been altered, misidentified, or misrepresented with the intention to commit fraud.

One way this is accomplished is through addition of a signature of a famous artist or altering the back of the frame to indicate a different or false provenance. The intention determines the act as fraud.

Forgery

Our next category of art crime is forgery. Charney defines forgeries as “object(s) made in fraudulent imitation of an existing item or the creation of an artwork that presumes to be something other than what it actually is” (Charney 2016, 34). Unlike fakes, criminals create new objects rather than modifying or misattributing an existing work.

Within the broader category of forgeries are two subcategories: referential and inventive. Referential forgeries are direct copies of an existing work (Hick and Gilmore 2023, 425). These are similar to copies but these works are meant to be considered original. Inventive forgeries are not reproductions of any singular work, but instead capture the style of an artist or period (Hick and Gilmore 2023, 425).

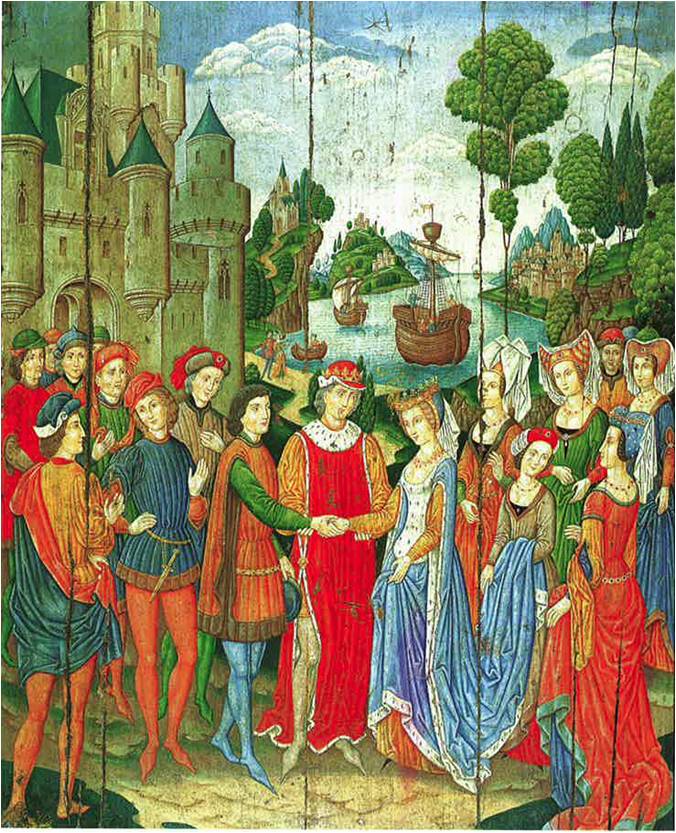

The identity of one of most well-known forgers of the twentieth century remains unknown. Named the “Spanish Forger” by scholars, they forged medieval manuscript illuminations and panel paintings. Active at the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, the Spanish Forger mimicked successfully the style of medieval art, which was especially popular at the time. They scraped paint from authentic medieval panels and parchment to pass scientific testing however the style was not quite right and in 1930, scholar Belle Da Costa Greene discovered the forger applied gold after painting in contrast to medieval practices of applying gold after the colors.

Art Theft

Art theft is a compelling and fascinating facet of the art crime world. When you imagine heists, you might think of movies and television shows, such as Oceans 11, Money Heist, Mission Impossible, and The Thomas Crown Affair. Cinema portrays exhilarating and exciting hefts and heists that are daring and successful.

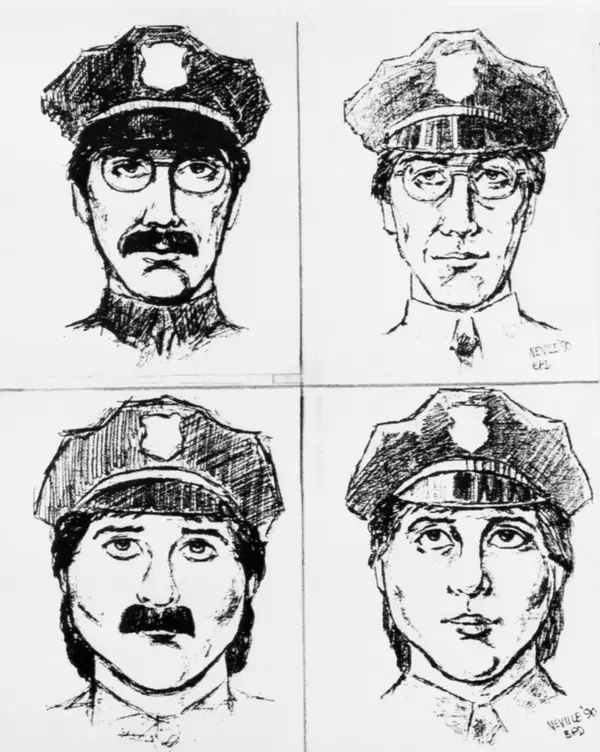

In the real world, art heists are much more complicated. During the early hours of March 18, 1990, two men dressed as police officers stole 13 works from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts in one of the most famous art crimes ever.

The criminals only needed 81 minutes to steal priceless works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Manet, Degas, and others. The case remains unsolved despite a $5 million dollar reward from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and a $10 million dollar reward from the museum for information leading to the safe return of the art. Investigators have tied the theft to the mob and mafia criminal network in Boston; however, they still do not have enough evidence to solve the crime.