“The guards were distracted, the crowds were full, and I was ready to commit a kidnapping”

The guards were distracted, the crowds were full, and I was ready to commit a kidnapping. It was also, I must add, not a dark and stormy night. That would have reduced my crowd cover, and made it much more difficult to complete my heist. During the century-long tenure of “William” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it gained widespread fame as a mascot for the cultural institution, and it made for a very interesting target, one that was both a test of my skill and personally lucrative.

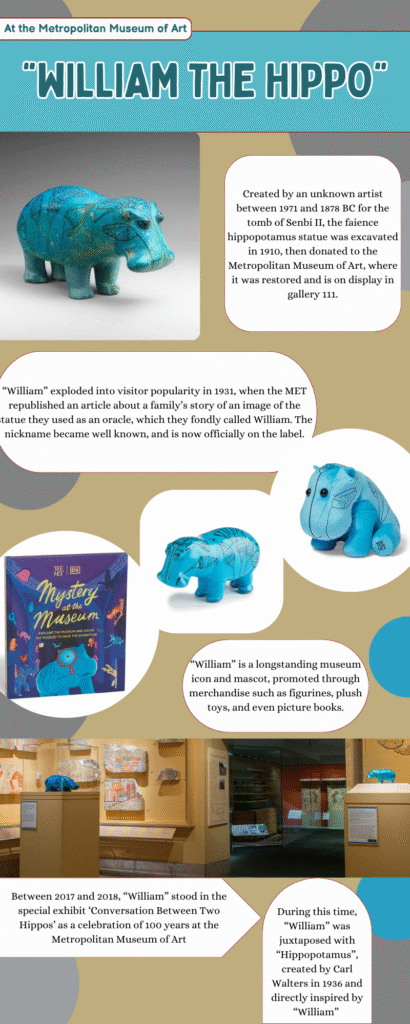

“William” is actually a nickname for a statue originally labeled “Hippopotamus”. Excavated from the tomb of ancient Egyptian steward Senbi II at an ancient Upper Egyptian Cemetery site in 1910, the statue spent a short amount of time in the hands of Edward S. Harkness before he donated his collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1917, where the statue has remained ever since, with the accession number 17.9.1. In 1931, the statue was noted in a magazine publication, as part of a humorous story in which a family used its image, which they called William, as an oracle. The MET republished the article, and the name stuck, as well as the endearing popularity of the small statue. Made of bright turquoise faience with black lotus imagery painted on, “William” is an eye-catching example of ancient Egyptian faience statuary.

Ancient Egyptian art may be incredibly popular on the market, both legally and illegally, but “William” is frankly too famous to sell. That’s why stealing “William” wasn’t just a theft, but a kidnapping. It’s an icon of the museum, a money making face. “William” is used in merchandise from ceramic replicas to picture books, and its fame grew even more after a special 100 year commemoration exhibit ‘Conversation Between Two Hippos’ in 2017, where it was on display with another hippo statue, “Hippopotamus” made in 1936 by Carl Walters, who was directly inspired by “William” to create his own faience hippopotamus.

The theft was for ransom, or for restitution. Reward money from the MET and the FBI was the goal I was after. Famous art pieces, important art pieces, were worth a lot of money to museums. An iconic statue that had been in the hands of the MET for over 100 years, drew continuous attention from the public, and recently had its own special exhibit, meant that “William” was an investment, and no gallery wants to lose their investments. In the unlikely event that law enforcement found me, “William” is good leverage for a reduced sentence or freedom as well.

My plan was simple. First, enter the MET as a perfectly law-abiding visitor. The best way to break in somewhere is to have permission, and there are many more benefits to entering during open hours compared to breaking in when the museum is closed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the largest art museum in the United States, with the security force and anti-theft technology to match, and museum guards are trained to never let people inside the building, to never leave the museum if an outside disturbance is noted, and to always call for help. This, combined with the sheer size of the building, makes breaking and entering outside of open hours an incredibly risky prospect. But entering with moderately concealed supplies during a new exhibition opening, or other public event means that I have all the time I need to get to the statue, and that physical security will be focused on the influx of visitors in a different area.

Second, remove “William” from its case. Public museums are inherently vulnerable due to the sheer number of people moving through them and interacting with the pieces, so with some effort, and practice, I could easily remove “William” from its case. Removing it quickly enough and without any museum visitors noticing, that was the tricky part, but I managed in time.

Once completed, and with no witnesses, I moved quickly to a secluded area with privacy, a restroom, to more securely hide the statue. While doing this, I also mildly changed my appearance with the use of hairstyle adjustments, fake glasses, and changing layers. The MET inspects large bags on the way in, so putting a sweater inside a bag meant that I transported my own disguise and made room for concealing the statue. Then, I moved swiftly to the exit before an alarm was raised.

Exits cannot be guarded in the same way entrances are, so once I was through, I was scott-free. Museums prioritize the retrieval of stolen objects more than identifying the perpetrator, and New York is big enough to lose a small country in. A good, simple, flexible plan that plays to my experience. That’s why I’m a professional thief. And “William” looked wonderful on my mantle before his ransom was fulfilled.

Bibliography

- Amore, A., Mashberg, T., (2011). “Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists” St. Martin’s Press

- Barelli, J., Schisgal, Z. (2019) “Stealing the Show: A History of Art and Crime in Six Thefts” Globe Pequot.

- Barnicle, C. (2021) “This is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist” Netflix

- Gill, D. W. (2015). Egyptian antiquities on the market. The management of Egypt’s cultural heritage, 2, 67-77. Ch_6_Looting_Egypt_Gill-libre.pdf

- Hardy, S. (2015) “Is looting-to-order “just a myth”? Open-source analysis of theft-to-order of cultural property” Cogent Social Sciences 1(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2015.1087110

- Keller, S (1995) “The Quandaries of Museum Security” The Journal of Museum Education 20(1). https://www.jstor.org/stable/40479484

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (2018) “Conversation Between Two Hippos” William the Hippo, Celebrating 100 Years at the Met” Conversation between Two Hippos | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Patch, Diana Craig 2015. “Standing Hippopotamus.” In Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom, edited by Adela Oppenheim, Dorothea Arnold, Dieter Arnold, and Kei Yamamoto. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 216–17, no. 156. Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom – Adela Oppenheim, Dorothea Arnold, Dieter Arnold, Kei Yamamoto – Google Books

- Serotta, A., Riccardelli, C., Schorsch, D. (2017) “Getting to Know “William” – Inside and Out. The MET Getting to Know “William”—Inside and Out – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Siemaszko, C. (2016) “Here’s Why Art Thieves Steal Paintings They Can’t Sell” NBC News. Here’s Why Art Thieves Steal Paintings They Can’t Sell

- Stunkel, I., Yamamoto, K. (2017) “How William the Hippo Got His Name” Now at the Met How William the Hippo Got His Name – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Thompson, M., Barelli, J. (2019) “What’s it like to be in charge of security at the Met Museum” PBSNewsHour. What’s it like to be in charge of security at the Met Museum?