Hero's

In the history of Major League Baseball (MLB), there have been only a handful of Jewish ballplayers, and even fewer have made a successful career out of playing the National Pastime. As a result, those few Jewish ballplayers who had a somewhat successful career took on near hero status among Jewish youths in the United States.

"The presence of professional heroes provided important role models for city youths, who aspired to a big league career, and there was fierce competition for places on amateur teams sponsored by schools, businesses, ethnic groups, and religious organizations." (Riess. 1980. P250)

While most of the Jewish players in the MLB had a decent career, only two have made their way to immortality in the Baseball Hall of Fame - Hank Greenberg (1911 - 1986) and Sandy Koufax (b.1935). While both were masters at their craft, the legacy of their careers will forever be connected to their Jewish heritage. Greenberg and Koufax played in two different eras of the game, but each faced the same religious question is deciding to play, or not, on Jewish Holidays. Whereas the two ballplayers came to different decisions, Greenberg gave a positive representation to the Jewish people in his 1934 Rosh Hashanah decision, and Koufax did the same with his actions in 1965. Both decisions, and their legacies, are explored here.

Baseball's First Jewish Superstar

Hank Greenberg, baseball's first Jewish superstar, broke down barriers and showed the second generation of Jewish-Americans that it was possible to be publically Jewish and simultaneously an American at the same time.

From 1930 to '47, Greenberg played in 13 seasons of Major League Baseball, 12 with the Detroit Tigers and one with the Pittsburg Pirates. However, he did not play baseball in the 1942, '43, or '44 seasons, due to the fact he was away fighting in World War II with the 29th Bomber Command. When he returned to the league, it was as if he never left. In his impressive, yet incomplete career, Greenberg had a .313 career batting average, hit 331 home-runs, and almost broke Babe Ruth's single season home-run record in 1938. Along with being a league All-Star 5 times, Greenberg won the league Most Valuable Player award twice - first in 1935 and again five years later in 1940. The two-time World Series champion was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956.

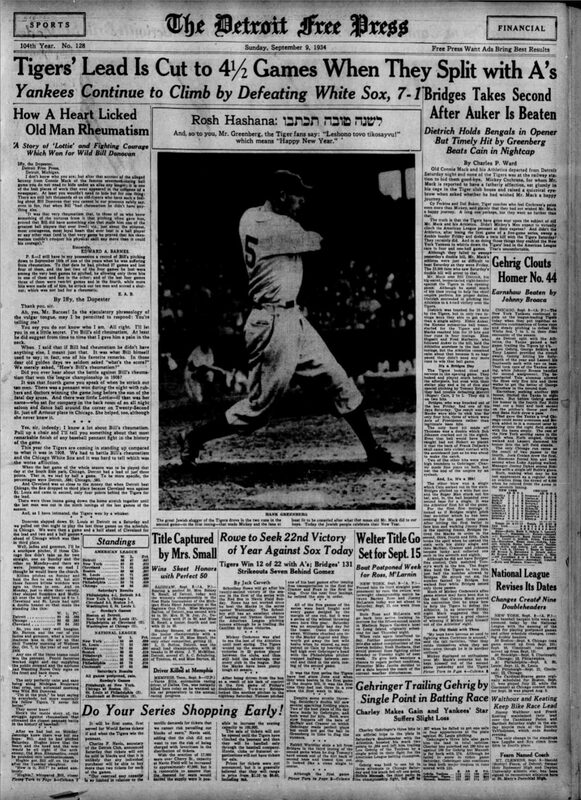

Greenberg, while not a very active member of the Jewish community, was keenly aware of his role beyond baseball and that Judaism was a part of his public identity, whether he wanted or not. References to Greenberg's Judaism, and the antisemitism that resulted from that knowledge, followed him everywhere throughout his career. The public's involvement in Greenberg's faith reached its heights towards the end of the 1934 season. That year the Detroit Tigers had the opportunity to do something the franchise had not since 1909 - win the pennant.

Rosh Hashanah, the holiday of the Jewish New Year, unfortunately fell on the same day the Tigers had a game against the Boston Red Sox. When Greenberg commented that he may not play, and attend synagogue instead, the press turned a small event into news across the country. The Red Sox would go on to finish 10th in the league that year, and the Tigers had maintained a 4-game lead over the New York Yankees in second place.

"The media assessed Greenberg's secular responsibilities from its impact on other people, which it largely eschewed in its examination of his religious responsibilities, the press portrayed the intense pressures converging on Greenberg as emanating largely from two competing value systems rather than from the articulated demands of specific individuals or groups or the press itself," (Simons. 1982. P101).

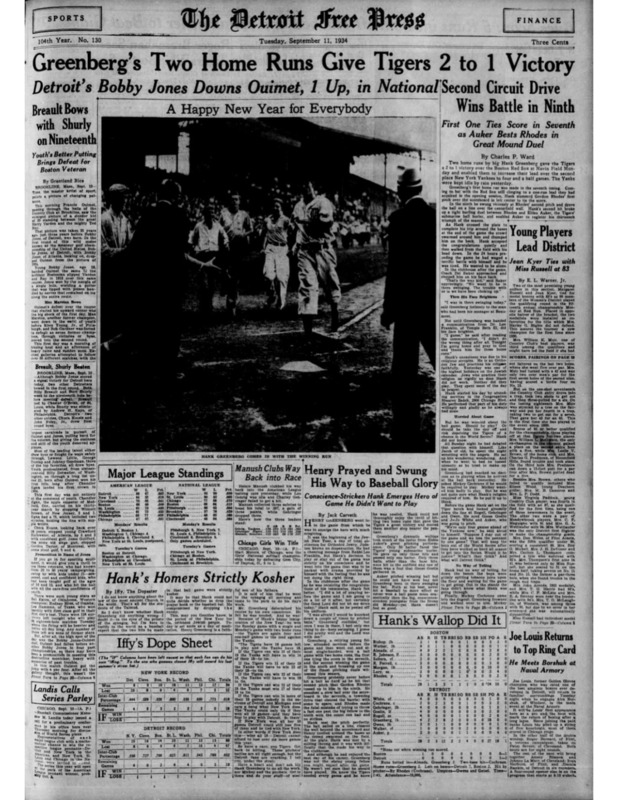

Eventually Greenberg chose to play in the Rosh Hashanah game, understanding that the city and the Tigers needed him that day. Hank hit two, solo home-runs, carrying the Tigers (2) to victory over the Red Sox (1). Greenberg, relieved the Rosh Hashanah decision was behind him, had a much easier choice on Yom Kippur, the Jewish holiday of atonement that comes 10 days after Rosh Hashanah. With the pennant secure Greenberg did not play on Yom Kippur, but the press agreeed he had 'earned' the day off. Below are four newspapers, from two different Detroit publications, that show the media response to Greenberg's decisions and actions ranging from Septemeber 9th to the 21st of 1934, encompassing the dates of both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

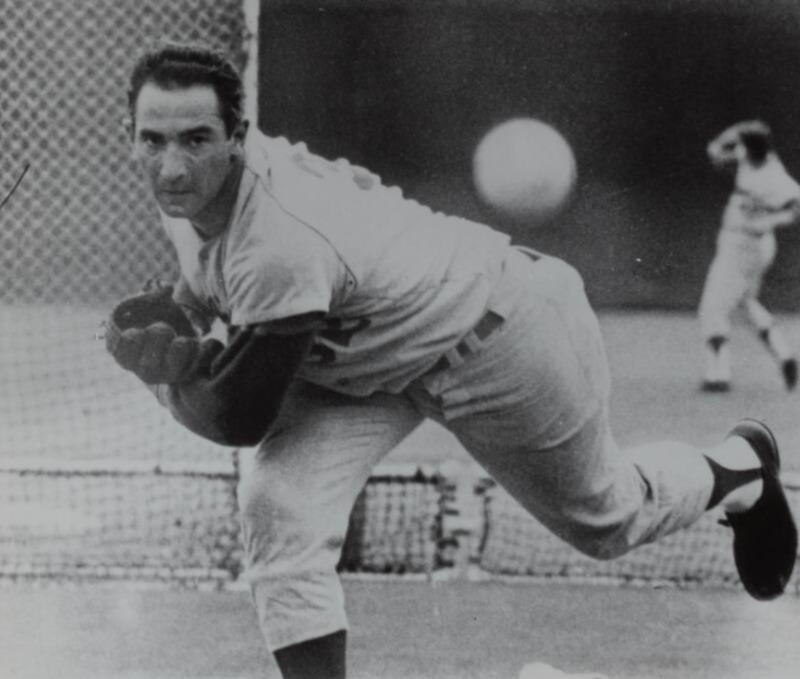

Gods Template for a Pitcher: Sandy Koufax

Whereas Hank Greenberg's career made him a hero in the eyes of many first and second generation Jewish-Americans, Sandy Koufax was the modern hero to bring baseball into its modern era. In his 12 year career Koufax pitched four no-hitters ,one as a perfect game, something not many other pitchers have done. Koufax won the league Most Valuable Player award in 1963, as well as the Cy Young Award for best pitcher in the league three times, while in the same seasons winning the pitching triple crown - leading the league in earned run average (ERA), strikeouts, and wins.

Koufax's dominance on the mound is unmatched. Through repeptive motions in his delivery, batters were able to determine what pitch he was about to throw, but he was still near unhittable. Willie Stargell, a hitter for the Pittsburg Pirates, once compared hitting off of Koufax to "drinking coffee with a fork".

Koufax held the status of baseball superstar more often than he was viewed as a Jewish baseball superstar. However the 1965 season would bring his Judaism to the national stage.

At the end of the '65 season Koufax would lead the league in wins, ERA, complete games, innings pitched, strikeouts, and batters faced; but none of that mattered when Game 1 of the World Series fell on Yom Kippur, the Jewish holiday of atonement. Wheres Greenberg's Rosh Hashanah decision was influenced by those around him, for Koufax, "there was never any decision to make...because there was never any possibility [he] would pitch. Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the Jewish Religion."

"Koufax was a secular Jew, but... he no doubt understood that for him the marquee star to pitch the first game of the World Series on Yom Kippur would be a blow to his people, a very public repudiation of their traditions. More would be lost - even if he won the game - than gained" (Rosenberg. 2015).

Don Drysdale (1936 - 1993), a future hall of famer, pitched Game one for the Dodgers, which they lost 7-1 to the Minnesota Twins. Koufax, however, came back with a vengance. After an uncharacteristic loss in Game Two, Koufax pitched complete-game shutouts in Games Five and Seven, willing the Dodgers to World Series Gloryince again.

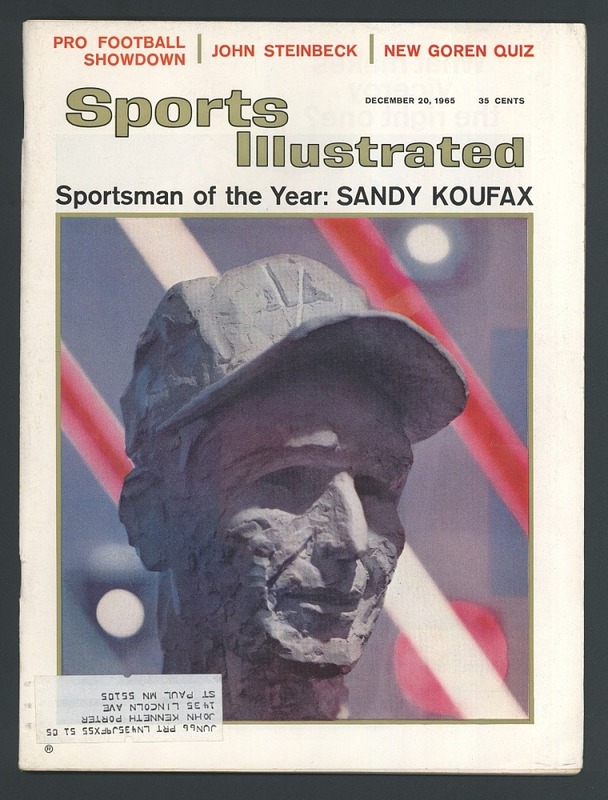

Interestingly, the public reaction to Koufax’s announcement was nearly the opposite to Greenberg's experience in 1934. “When Sports Illustrated named [Koufax] its Sportsman of the Year for 1965, there was no mention of that decision – or of Yom Kippur or Judaism at all – in its nearly 7,000-word interview with Koufax that ran as the cover story of the Dec. 20 issue.” (Rosenberg, 2015)