Legends

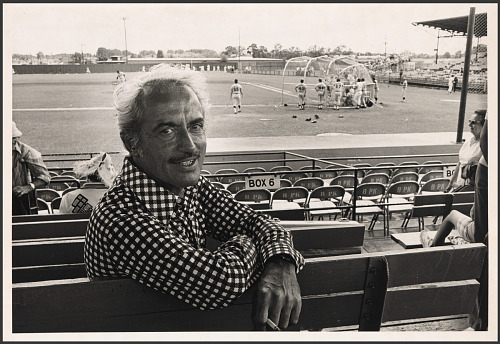

Marvin Miller (1917 - 2012) was hired to be the first Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Player's Union in 1966. He had worked for the National War Labor Board, United Auto Workers, and had spent the last 16 years of his career with the United States Steelworkers Union, eventually as the Unions chief economist, advisor, and assistant to the President.

A divisive election left miller stuck between his job, and his mentor who had been just lost his re-election bid for union President. He left the union unsure about his next opportunity, but eventually found himself in an interview to become executive director of the historically innefective MLB Players Union. Excited at the chance to build a union from the ground up, Miller saw the opportunity as one in which he "could't fail... That anything [the players] did was going to be a big improvement" (Oral History P.22).

After a interview in which he strongly objected to the player representative's choice for general counsel, former Vice-President and soon to be President Richard Nixon, and feeling he "had blown it", Miller had earned the role. The player representatives, and then the players were continually impressed with Miller's insight and calm demeanor. Additionally, "Miller was more pro-player than many of the players were. And while some took a while to trust him and buy into the idea that baseball players needed a union, they all backed him in time," (Haupert).

Longtime baseball play-by-play commentator Red Barber once labeled Marvin Miller as "one of the three most important men in baseball history," alongside Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson.

When Miller was hired by the MLB Players Union in 1966, the minimum league sallary was $6,000 and the average was $17,664 (CBU P342). Until Miller's hiring, the owners had funded union but suddenly felt it was no longer in their best interest. When Miller was hired the union had a little under $6,000 on hand, but a license agreement with Coca-Cola and a restructuring of the player pension plan cemented the union as financially sound organization.

With a big victory in his frst year on the job already behind him, Miller took another big swing before the 1968 season. In Februrary of 1968 Miller and the players negotiated the first collective bargaining agreement in professional sports history. The '68 agreement raised the leagues minimim salary of $6,000 to $10,000.

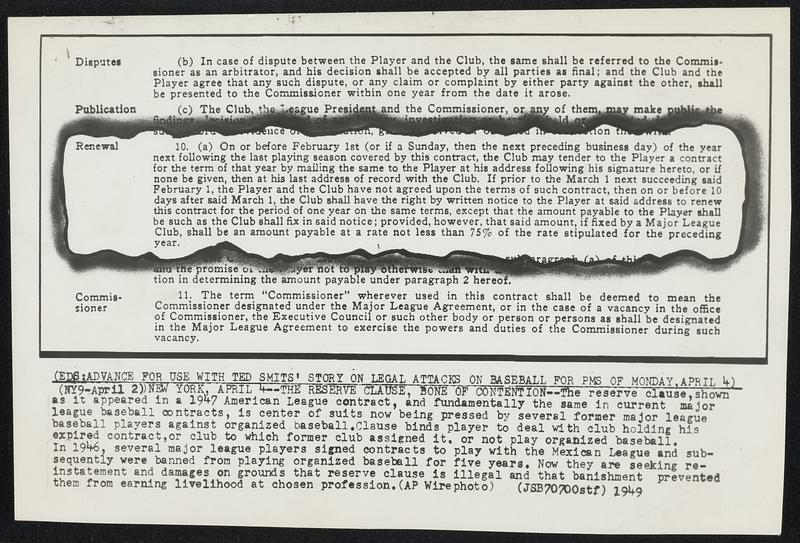

Miller's toughest test came in 1969 when Curt Flood, a star center-fielder in the league was traded from the St. Louis Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies. Refusing to live or work in Philadelphia, Flood objected to the trade and challenged The Reserve Clause, a then standard clause that had appeared in every contract since 1897. According to Miller, the Reserve Clause made it so if a player "didn't sign the contract for the next year, under the contract [he] had previously signed, the club reserved the rights to [him] indefinitely."

The Reserve Clause, seen to the right, reads;

On or before December 20 (or if a Sunday, then the next preceding business day) in the year of the last playing season covered by the contract, the Club may tender to the Player a contract for them term of that year by mailing the same to the Player at his address following his signature hereto, or if none given, then at his last address of record with the Club. If prior to March 1 next suceeding said December 20, the Player and the Club have not agreed upon the terms of such contract, then on or before 10 days after March 1, the Club shall have the right by written notice to the Player at said address to renew this cotract for the period of one year on the same terms, except that the amount payable to the Player shall be such as the blub hsall fix in said notice; prvided, however, that said amount, if fixed by a Major League Club, shall be an amount payable at a rate not less than 80 percent of the rate stipulated fro the next preceding year and at a rate not less than 7- percent of the rate stipulated for the year immediately prior to the next preceding game.

Although Curt Flood lost in his challenge of the Reserve Clause, and he never played professional baseball again, Miller and the player's union stood with Flood all the way to the United States Supreme Court. The result of Flood's courage and determination throughout the lengthy battle inspired the players still in the league and solidified the unity and strength of the players. Although the reserve clause survived the Flood trial, It came to an end in 1975, when an arbitrator ruled against the owners and the Reserve Clause, establishing free agency among the players.

Legacied Success

In the sixteen years Marvin Miller led the Major League Baseball Player's Union, he led the charge in reshaping an industry that continues to grow and benefit from his work. Miller made it so players had access to a grievence process and impartial arbitrators, were liberated from the shackles of the Reserve Clause, and saw a tremendous increase in pension and other benefits.

In 1966, Miller's first year on the job, the average salary in Major League Baseball was $17,664. When he retired in 1983, the average salary in the MLB had risen to $289,000.

Under Marvin Miller's leadership "the union has created salary arbitration, free agency, impartial arbitation of grievances, dealing with interpreting a player's contract, interpreting the basic agrement and how it affects a player. The union has policed a free market for players with its insistence upon collusion of the owners ending, and it did that successfully" (Celebration of Baseball Unionism, 362).