-

Mexican gang of migratory laborers under a Japanese field boss. These men are thinning and weeding cantaloupe plants. Wages thirty cents an hour

Mexican gang of migratory laborers under a Japanese field boss. These men are thinning and weeding cantaloupe plants. Wages thirty cents an hour This photo by Dorothea Lange captures Mexican migrant workers picking cantaloupe for thirty cents an hour. Migrant workers faced up to twelve hour days in the sun without breaks, water, or adequate facilities, such as outdoor bathrooms. Some laborers reported sharing only one pitcher or can of water in extreme cases. Besides the threat of heat stroke and dehydration, workers also faced health issues from exposure to harmful pesticides like DDT.

-

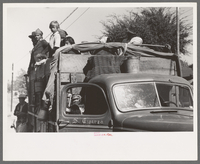

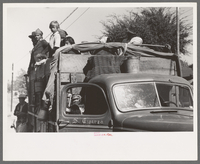

Truckload of Mexican migrants returning to their homes in the Rio Grande Valley from Mississippi where they had been picking cotton. Neches, Texas

Truckload of Mexican migrants returning to their homes in the Rio Grande Valley from Mississippi where they had been picking cotton. Neches, Texas Mexican migrant workers frequently traveled long distances to work for very low wages on American Farms. While some workers were able to find temporary housing on the farms where they worked, others commuted hundreds of miles both ways to toil in the fields. In this photo, a family of Mexican migrant workers traveled over six hundred miles from Texas to Mississippi to pick cotton. Early migrant workers also had to find their own means of transportation, which meant that they spent a large portion of their earnings traveling to and from the fields.

-

Mexican migrant housing. Edcouch, Texas

Mexican migrant housing. Edcouch, Texas This photo captures the living conditions of Mexican migrant laborers in Texas during the 1930s. The houses were often poorly constructed, lacking heat, indoor plumbing, or sufficient space for workers and their families. Insects and other pests infested the houses regularly, making the inhabitants more vulnerable to diseases and other health issues. Migrant workers expressed their concerns about the unsanitary conditions of their housing, as well as the inaccessibility to important resources like medical facilities and grocery stores, but owners of the farms frequently ignored their complaints.

-

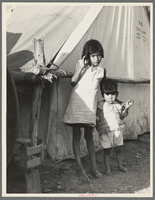

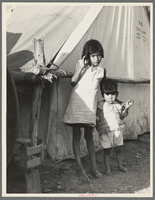

Migrant Mexican children in contractor's camp at time of early pea harvest. Nipomo, California

Migrant Mexican children in contractor's camp at time of early pea harvest. Nipomo, California Mexican migrants frequently traveled in families, meaning that children often worked in the fields and faced exposure to harmful pesticides and back breaking labor. The children of migrant workers found it difficult to completely embrace their lives in both Mexico and the United States, feeling like outsiders to both cultures. Children who attended schools in the United States struggled against racism and discrimination for not speaking fluent English or assimilating to Anglo-American culture. Not all migrant children were able to receive an education, however, due to frequent moves and their family’s economic reliance on their labor. Those who later returned to Mexico also faced judgment for contributing to the growth of the American economy while Mexico’s economy struggled amidst political instability. While migrant children were especially influenced by their experiences on migrant farms between the 1930s and 1970s, little provisions or legal rights were granted to migrant children even under the United Farm Workers movement.

-

Cantaloupe Pickers, Mexicans, at End of Day in California Melon Fields / Mexican Labor Off for the Melon Fields in the Imperial Valley, California

Cantaloupe Pickers, Mexicans, at End of Day in California Melon Fields / Mexican Labor Off for the Melon Fields in the Imperial Valley, California This photograph from 1935 captures Mexican migrant workers in California heading home after working in the melon fields. Mexicans migrated to the American Southwest in the 1930s searching for work after turbulent political affairs at home resulted in a domestic labor shortage. Most workers migrated from the northern border of Mexico, but some laborers commuted from as far as Mexico’s central region in search of work. Dorothea Lange took this photo as part of a project commissioned by the Farm Security Administration to advocate against rural poverty. She became interested in the plight of migrant workers through her work with the FSA and used photography to advocate for better working conditions on the migrant farms.

-

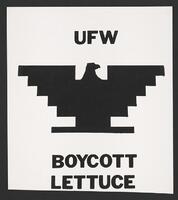

UFW Boycott Lettuce.

UFW Boycott Lettuce. This image features the symbol of the United Farm Workers labor union founded in 1962. The eagle was designed by Richard Chavez, brother of the UFW’s founder Cesar Chavez, and drew on the iconographic style of the Aztecs. Using the Aztec eagle was a way to connect the UFW to the Mexican heritage of its members and further legitimize the movement. Richard Chavez also designed the symbol in a simple style that would be easy to reproduce on posters, signs, and other materials used during protests and boycotts. The eagle was also featured on legal documents, such as contract negotiations, and became an important emblem of the UFW’s successes.

-

Title sheet, site plan, map, and entrance sign - Forty Acres, 30168 Garces Highway (Northwest Corner of Garces Highway and Mettler Avenue), Delano, Kern County, CA

Title sheet, site plan, map, and entrance sign - Forty Acres, 30168 Garces Highway (Northwest Corner of Garces Highway and Mettler Avenue), Delano, Kern County, CA In 1966, the United Farm Workers built their first headquarters in Delano, California. These drawings are an early rendering of the site plan for the Forty Acres compound where Cesar Chavez publicly fasted for the first time and where the UFW bargained with farmers for migrant workers’ rights. The UFW started construction on the site in August of 1967, building a small gas station for migrant workers to access affordable gasoline for their personal vehicles. Forty Acres also featured a service center that offered health services, childcare, legal services, banking, and affordable groceries for migrant workers in the area. The buildings in Forty Acres were inspired by the architecture of the Spanish colonial style that Cesar Chavez admired. The National Park Service added the site to its register of Historic Landmarks in October of 2008 for its importance to Hispanic culture and heritage.

-

Democratic Convention in New York City, July 14, 1976. [Cesar Chavez at podium, nominating Gov. Brown.]

Democratic Convention in New York City, July 14, 1976. [Cesar Chavez at podium, nominating Gov. Brown.] Photographed here is Cesar Chavez, political activist and leader of the United Farm Workers’ movement, at the Democratic Party Convention in 1976. The UFW had connections with the Democratic Party that dated back to the 1960s and were continually supported by Democratic politicians. In 1968, former New York Senator and member of the Democratic Party, Robert Kennedy, visited Cesar Chavez as he broke his twenty-five day fast. Kennedy gave several speeches throughout the late 60s in support of the UFW and migrant worker’s concerns. In return, Chavez and the UFW supported Kennedy when he ran for President in 1968. Though Kennedy was assassinated before the election, the UFW and Cesar Chavez remained active with the Democratic Party and its leaders.

-

Lincoln, Statue of Liberty and Cesar Chavez, Restaurant Paseo San Miguel, Salvadorian Cuisine, 1560 West Martin Luther King Blvd. at La Salle St., Los Angeles, 2016

Lincoln, Statue of Liberty and Cesar Chavez, Restaurant Paseo San Miguel, Salvadorian Cuisine, 1560 West Martin Luther King Blvd. at La Salle St., Los Angeles, 2016 This mural in the parking lot of a restaurant in Los Angeles, California, depicts the leader of the United Farm Workers’ movement, Cesar Chavez, alongside former President Abraham Lincoln and the Statue of Liberty. By pairing Chavez with popular American icons, the artist conveys Chavez’s cultural importance and the historical significance of his involvement with migrant farm workers in the American Southwest. The colors used in the background of the mural are red, white, and green, which represent the colors of the Mexican flag and further draw connections between the United States and Mexico’s long political history.

-

A portion of artist Melchor Ramirez's mural honoring Chicano activist Cesar Chavez in a small park bearing Chavez's name in Tucson, Arizona.

A portion of artist Melchor Ramirez's mural honoring Chicano activist Cesar Chavez in a small park bearing Chavez's name in Tucson, Arizona. This image displays a portion of a mural created by the artist Melchor Ramirez in Tucson, Arizona. The mural depicts the leader of the United Farm Workers organization, Cesar Chavez, in traditional Aztec clothing and draws upon iconography from Aztec art to emphasize Chavez’s Mexican heritage. Seated next to Chavez is the Aztec goddess of fertility and harvest, Tonantzin, which further alludes to Chavez’s political ties to migrant farm workers and the UFW.

-

The Lumberjack, October 22, 1968.

The Lumberjack, October 22, 1968. This 1968 edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, features an article about racism and racial identity amongst Mexican-Americans. The Lumberjack interviewed Hispanic faculty members and students to get perspective on their experiences as Mexican-Americans in the late 1960s. A local teacher asserted that racial tensions began with the first Mexican migrant workers who did not speak English or assimilate to Anglo-American culture. One NAU student, Margaret Valdez, further explained the development of a Mexican-American inferiority complex that developed amongst first generation Mexican-Americans whose parents immigrated to the United States as farm laborers.

-

The Lumberjack, April 5, 2007.

The Lumberjack, April 5, 2007. This 2007 edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, covered the third annual Cesar Chavez march in Flagstaff, Arizona. The article provides insight into some of the important reforms that the United Farm Workers association secured for migrant farm workers in the American Southwest, including better wages and working conditions. Participants praised the UFW’s leaders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta for their political activism which was responsible for such reforms. They carried posters bearing the UFW’s symbol, pictures of Cesar Chavez, and other symbols from the Civil Rights movement such as the raised fist. NAU’s Hispanic student organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A), founded the annual march in April of 2005. Subsequent marches, like this one from 2007, brought Flagstaff’s Hispanic population together to celebrate their heritage and cultural icons.

-

The Lumberjack, April 14, 2005.

The Lumberjack, April 14, 2005. This edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, features an article about the first annual Cesar Chavez march in April of 2005. The march was organized by a Hispanic student organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A), at NAU to honor the memory of the United Farm Workers’ leader. M.E.Ch.A hoped to raise awareness about the important role that Cesar Chavez played in the fight for Hispanic migrant workers’ rights as well as his influence on the overall Chicano population of the United States. The march started at the first Chicano church in Flagstaff, Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, and continued on through the city of Flagstaff, Arizona.

-

Couple with Woman Wearing Sombrero with UFW Symbol

Couple with Woman Wearing Sombrero with UFW Symbol When the Bracero Program ended in 1964, many farms turned to prisons in the Southwest for another source of cheap labor. Mexican Americans, who were widely incarcerated due to racial profiling by the police and border patrol, once again found their labor exploited by big agricultural farms. As late as 1978, prisons used Mexican American prisoners to pick cotton for no pay. Strikes and protests were rare in these prisons, but those that emerged drew inspiration from the United Farm Workers’ movement of the early 1960s to advocate for shorter work weeks and better working conditions. This drawing captures the connection between labor activism in the prisons and the farmworkers movement. The artist depicts a guard tower and a cell to represent prison laborers with a woman in the foreground wearing a sombrero that bears the United Farm Workers’ symbol.

-

César Chávez’s Union Jacket

César Chávez’s Union Jacket This jacket was worn by Cesar Chavez who founded the United Farm Workers movement in 1962. Chavez and his associates dedicated their lives to improving the working and living conditions of Hispanic migrant farm workers in the United States. The United Farm Workers utilized boycotts and strikes, popular methods of political resistance in the 1960s, to communicate their demands to individual farmers and the American public. Cesar Chavez also drew on other tactics used by his political inspirations, such as Mahatma Gandhi, and partook in hunger strikes to encourage farmers to listen to the pleas of the farmworkers. Chavez remained politically active up to his death in 1993. Former President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded Cesar Chavez the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994.

-

¡Huelga!: The Plight of Farmworkers

¡Huelga!: The Plight of Farmworkers This clip from Skeets McGrew’s 1965 film ¡Huelga! captures the living conditions of migrant farm workers in Delano, California. In this section of McGrew’s documentary, farm owners shared their opinions on the strikes and responded to the demands of the workers with little sympathy. The leadership of the United Farm Workers, which included Cesar Chavez, produced this film to highlight the plight of migrant workers and encourage Americans across the country to support their boycott of Delano grapes.

-

Huelguistas: Delano Grape Strikers Oral History 1965, Maria Saludado

Huelguistas: Delano Grape Strikers Oral History 1965, Maria Saludado A migrant farmworker and member of the Delano Grape Strike of 1965, Maria Saludado, recounts her experiences immigrating to the United States in the 1950s and working in American fields for ten cents an hour. She details the struggles of growing up in Chula Vista and San Diego, California from her attempts to get along with her Anglo American peers to the backbreaking labor that she and her entire family experienced in the fields. Saludado also details the health problems she contracted, such as asthma, from the pesticides used in the fields where she worked. Her story highlights the experiences of Mexican migrant workers in Delano during the 1950s and 60s, exploring the many issues they faced like low wages, health hazards, poor working and living conditions, and racial discrimination.

-

Pesticides Kill Farmworkers—1990

Pesticides Kill Farmworkers—1990 Cesar Chavez, a leader of the United Farmworkers Movement, discusses the health concerns of using the pesticide DDT in the fields. Chavez details the boycott of 1965 which urged grape growers to eliminate their use of pesticides because of farmworkers who developed cancer, experienced birth defects, and other health issues after exposure to DDT. He also explores the emergence of cancer clusters due to pesticide use in vineyards and other agricultural sites in the Silicon Valley of California. Chavez recounts the success of the 1965 boycott and uses it as motivation for farmworkers in the 1990s to take up the fight against another deadly pesticide, organophosphates.

-

Paul Taylor with Migrant Workers, Imperial Valley, California

Paul Taylor with Migrant Workers, Imperial Valley, California Dorothea Lange’s husband, Paul Taylor, stands with a family of migrant farm workers in California. Taylor was a professor of economics and became interested in the plight of Mexican migrant workers after receiving his PhD in Labor Economics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1922. Lange took this photograph early in her relationship with Taylor during a trip in 1935 to document the lives of farm workers throughout California. It displays the poor living conditions of workers who toiled in the fields for very little money. The couple used photography to highlight the struggles that migrant workers faced and encourage political action to improve their living conditions.

-

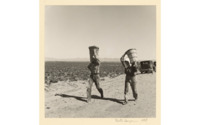

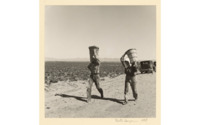

Farm Workers, South of Tracy, California

Farm Workers, South of Tracy, California Two farm workers, a couple, carry produce on their shoulders in the hot California sun. The weight of their produce was then used to determine their payment as part of the migrant worker program. The Farm Security Administration commissioned Dorothea Lange in 1938 to visit such farms in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia, Missouri, and California. Lange used her photography to advocate for better working conditions for migrant workers after witnessing their plight in the workers’ camps.

Mexican gang of migratory laborers under a Japanese field boss. These men are thinning and weeding cantaloupe plants. Wages thirty cents an hour This photo by Dorothea Lange captures Mexican migrant workers picking cantaloupe for thirty cents an hour. Migrant workers faced up to twelve hour days in the sun without breaks, water, or adequate facilities, such as outdoor bathrooms. Some laborers reported sharing only one pitcher or can of water in extreme cases. Besides the threat of heat stroke and dehydration, workers also faced health issues from exposure to harmful pesticides like DDT.

Mexican gang of migratory laborers under a Japanese field boss. These men are thinning and weeding cantaloupe plants. Wages thirty cents an hour This photo by Dorothea Lange captures Mexican migrant workers picking cantaloupe for thirty cents an hour. Migrant workers faced up to twelve hour days in the sun without breaks, water, or adequate facilities, such as outdoor bathrooms. Some laborers reported sharing only one pitcher or can of water in extreme cases. Besides the threat of heat stroke and dehydration, workers also faced health issues from exposure to harmful pesticides like DDT. Truckload of Mexican migrants returning to their homes in the Rio Grande Valley from Mississippi where they had been picking cotton. Neches, Texas Mexican migrant workers frequently traveled long distances to work for very low wages on American Farms. While some workers were able to find temporary housing on the farms where they worked, others commuted hundreds of miles both ways to toil in the fields. In this photo, a family of Mexican migrant workers traveled over six hundred miles from Texas to Mississippi to pick cotton. Early migrant workers also had to find their own means of transportation, which meant that they spent a large portion of their earnings traveling to and from the fields.

Truckload of Mexican migrants returning to their homes in the Rio Grande Valley from Mississippi where they had been picking cotton. Neches, Texas Mexican migrant workers frequently traveled long distances to work for very low wages on American Farms. While some workers were able to find temporary housing on the farms where they worked, others commuted hundreds of miles both ways to toil in the fields. In this photo, a family of Mexican migrant workers traveled over six hundred miles from Texas to Mississippi to pick cotton. Early migrant workers also had to find their own means of transportation, which meant that they spent a large portion of their earnings traveling to and from the fields. Mexican migrant housing. Edcouch, Texas This photo captures the living conditions of Mexican migrant laborers in Texas during the 1930s. The houses were often poorly constructed, lacking heat, indoor plumbing, or sufficient space for workers and their families. Insects and other pests infested the houses regularly, making the inhabitants more vulnerable to diseases and other health issues. Migrant workers expressed their concerns about the unsanitary conditions of their housing, as well as the inaccessibility to important resources like medical facilities and grocery stores, but owners of the farms frequently ignored their complaints.

Mexican migrant housing. Edcouch, Texas This photo captures the living conditions of Mexican migrant laborers in Texas during the 1930s. The houses were often poorly constructed, lacking heat, indoor plumbing, or sufficient space for workers and their families. Insects and other pests infested the houses regularly, making the inhabitants more vulnerable to diseases and other health issues. Migrant workers expressed their concerns about the unsanitary conditions of their housing, as well as the inaccessibility to important resources like medical facilities and grocery stores, but owners of the farms frequently ignored their complaints. Migrant Mexican children in contractor's camp at time of early pea harvest. Nipomo, California Mexican migrants frequently traveled in families, meaning that children often worked in the fields and faced exposure to harmful pesticides and back breaking labor. The children of migrant workers found it difficult to completely embrace their lives in both Mexico and the United States, feeling like outsiders to both cultures. Children who attended schools in the United States struggled against racism and discrimination for not speaking fluent English or assimilating to Anglo-American culture. Not all migrant children were able to receive an education, however, due to frequent moves and their family’s economic reliance on their labor. Those who later returned to Mexico also faced judgment for contributing to the growth of the American economy while Mexico’s economy struggled amidst political instability. While migrant children were especially influenced by their experiences on migrant farms between the 1930s and 1970s, little provisions or legal rights were granted to migrant children even under the United Farm Workers movement.

Migrant Mexican children in contractor's camp at time of early pea harvest. Nipomo, California Mexican migrants frequently traveled in families, meaning that children often worked in the fields and faced exposure to harmful pesticides and back breaking labor. The children of migrant workers found it difficult to completely embrace their lives in both Mexico and the United States, feeling like outsiders to both cultures. Children who attended schools in the United States struggled against racism and discrimination for not speaking fluent English or assimilating to Anglo-American culture. Not all migrant children were able to receive an education, however, due to frequent moves and their family’s economic reliance on their labor. Those who later returned to Mexico also faced judgment for contributing to the growth of the American economy while Mexico’s economy struggled amidst political instability. While migrant children were especially influenced by their experiences on migrant farms between the 1930s and 1970s, little provisions or legal rights were granted to migrant children even under the United Farm Workers movement. Cantaloupe Pickers, Mexicans, at End of Day in California Melon Fields / Mexican Labor Off for the Melon Fields in the Imperial Valley, California This photograph from 1935 captures Mexican migrant workers in California heading home after working in the melon fields. Mexicans migrated to the American Southwest in the 1930s searching for work after turbulent political affairs at home resulted in a domestic labor shortage. Most workers migrated from the northern border of Mexico, but some laborers commuted from as far as Mexico’s central region in search of work. Dorothea Lange took this photo as part of a project commissioned by the Farm Security Administration to advocate against rural poverty. She became interested in the plight of migrant workers through her work with the FSA and used photography to advocate for better working conditions on the migrant farms.

Cantaloupe Pickers, Mexicans, at End of Day in California Melon Fields / Mexican Labor Off for the Melon Fields in the Imperial Valley, California This photograph from 1935 captures Mexican migrant workers in California heading home after working in the melon fields. Mexicans migrated to the American Southwest in the 1930s searching for work after turbulent political affairs at home resulted in a domestic labor shortage. Most workers migrated from the northern border of Mexico, but some laborers commuted from as far as Mexico’s central region in search of work. Dorothea Lange took this photo as part of a project commissioned by the Farm Security Administration to advocate against rural poverty. She became interested in the plight of migrant workers through her work with the FSA and used photography to advocate for better working conditions on the migrant farms. UFW Boycott Lettuce. This image features the symbol of the United Farm Workers labor union founded in 1962. The eagle was designed by Richard Chavez, brother of the UFW’s founder Cesar Chavez, and drew on the iconographic style of the Aztecs. Using the Aztec eagle was a way to connect the UFW to the Mexican heritage of its members and further legitimize the movement. Richard Chavez also designed the symbol in a simple style that would be easy to reproduce on posters, signs, and other materials used during protests and boycotts. The eagle was also featured on legal documents, such as contract negotiations, and became an important emblem of the UFW’s successes.

UFW Boycott Lettuce. This image features the symbol of the United Farm Workers labor union founded in 1962. The eagle was designed by Richard Chavez, brother of the UFW’s founder Cesar Chavez, and drew on the iconographic style of the Aztecs. Using the Aztec eagle was a way to connect the UFW to the Mexican heritage of its members and further legitimize the movement. Richard Chavez also designed the symbol in a simple style that would be easy to reproduce on posters, signs, and other materials used during protests and boycotts. The eagle was also featured on legal documents, such as contract negotiations, and became an important emblem of the UFW’s successes. Title sheet, site plan, map, and entrance sign - Forty Acres, 30168 Garces Highway (Northwest Corner of Garces Highway and Mettler Avenue), Delano, Kern County, CA In 1966, the United Farm Workers built their first headquarters in Delano, California. These drawings are an early rendering of the site plan for the Forty Acres compound where Cesar Chavez publicly fasted for the first time and where the UFW bargained with farmers for migrant workers’ rights. The UFW started construction on the site in August of 1967, building a small gas station for migrant workers to access affordable gasoline for their personal vehicles. Forty Acres also featured a service center that offered health services, childcare, legal services, banking, and affordable groceries for migrant workers in the area. The buildings in Forty Acres were inspired by the architecture of the Spanish colonial style that Cesar Chavez admired. The National Park Service added the site to its register of Historic Landmarks in October of 2008 for its importance to Hispanic culture and heritage.

Title sheet, site plan, map, and entrance sign - Forty Acres, 30168 Garces Highway (Northwest Corner of Garces Highway and Mettler Avenue), Delano, Kern County, CA In 1966, the United Farm Workers built their first headquarters in Delano, California. These drawings are an early rendering of the site plan for the Forty Acres compound where Cesar Chavez publicly fasted for the first time and where the UFW bargained with farmers for migrant workers’ rights. The UFW started construction on the site in August of 1967, building a small gas station for migrant workers to access affordable gasoline for their personal vehicles. Forty Acres also featured a service center that offered health services, childcare, legal services, banking, and affordable groceries for migrant workers in the area. The buildings in Forty Acres were inspired by the architecture of the Spanish colonial style that Cesar Chavez admired. The National Park Service added the site to its register of Historic Landmarks in October of 2008 for its importance to Hispanic culture and heritage. Democratic Convention in New York City, July 14, 1976. [Cesar Chavez at podium, nominating Gov. Brown.] Photographed here is Cesar Chavez, political activist and leader of the United Farm Workers’ movement, at the Democratic Party Convention in 1976. The UFW had connections with the Democratic Party that dated back to the 1960s and were continually supported by Democratic politicians. In 1968, former New York Senator and member of the Democratic Party, Robert Kennedy, visited Cesar Chavez as he broke his twenty-five day fast. Kennedy gave several speeches throughout the late 60s in support of the UFW and migrant worker’s concerns. In return, Chavez and the UFW supported Kennedy when he ran for President in 1968. Though Kennedy was assassinated before the election, the UFW and Cesar Chavez remained active with the Democratic Party and its leaders.

Democratic Convention in New York City, July 14, 1976. [Cesar Chavez at podium, nominating Gov. Brown.] Photographed here is Cesar Chavez, political activist and leader of the United Farm Workers’ movement, at the Democratic Party Convention in 1976. The UFW had connections with the Democratic Party that dated back to the 1960s and were continually supported by Democratic politicians. In 1968, former New York Senator and member of the Democratic Party, Robert Kennedy, visited Cesar Chavez as he broke his twenty-five day fast. Kennedy gave several speeches throughout the late 60s in support of the UFW and migrant worker’s concerns. In return, Chavez and the UFW supported Kennedy when he ran for President in 1968. Though Kennedy was assassinated before the election, the UFW and Cesar Chavez remained active with the Democratic Party and its leaders. Lincoln, Statue of Liberty and Cesar Chavez, Restaurant Paseo San Miguel, Salvadorian Cuisine, 1560 West Martin Luther King Blvd. at La Salle St., Los Angeles, 2016 This mural in the parking lot of a restaurant in Los Angeles, California, depicts the leader of the United Farm Workers’ movement, Cesar Chavez, alongside former President Abraham Lincoln and the Statue of Liberty. By pairing Chavez with popular American icons, the artist conveys Chavez’s cultural importance and the historical significance of his involvement with migrant farm workers in the American Southwest. The colors used in the background of the mural are red, white, and green, which represent the colors of the Mexican flag and further draw connections between the United States and Mexico’s long political history.

Lincoln, Statue of Liberty and Cesar Chavez, Restaurant Paseo San Miguel, Salvadorian Cuisine, 1560 West Martin Luther King Blvd. at La Salle St., Los Angeles, 2016 This mural in the parking lot of a restaurant in Los Angeles, California, depicts the leader of the United Farm Workers’ movement, Cesar Chavez, alongside former President Abraham Lincoln and the Statue of Liberty. By pairing Chavez with popular American icons, the artist conveys Chavez’s cultural importance and the historical significance of his involvement with migrant farm workers in the American Southwest. The colors used in the background of the mural are red, white, and green, which represent the colors of the Mexican flag and further draw connections between the United States and Mexico’s long political history. A portion of artist Melchor Ramirez's mural honoring Chicano activist Cesar Chavez in a small park bearing Chavez's name in Tucson, Arizona. This image displays a portion of a mural created by the artist Melchor Ramirez in Tucson, Arizona. The mural depicts the leader of the United Farm Workers organization, Cesar Chavez, in traditional Aztec clothing and draws upon iconography from Aztec art to emphasize Chavez’s Mexican heritage. Seated next to Chavez is the Aztec goddess of fertility and harvest, Tonantzin, which further alludes to Chavez’s political ties to migrant farm workers and the UFW.

A portion of artist Melchor Ramirez's mural honoring Chicano activist Cesar Chavez in a small park bearing Chavez's name in Tucson, Arizona. This image displays a portion of a mural created by the artist Melchor Ramirez in Tucson, Arizona. The mural depicts the leader of the United Farm Workers organization, Cesar Chavez, in traditional Aztec clothing and draws upon iconography from Aztec art to emphasize Chavez’s Mexican heritage. Seated next to Chavez is the Aztec goddess of fertility and harvest, Tonantzin, which further alludes to Chavez’s political ties to migrant farm workers and the UFW. The Lumberjack, October 22, 1968. This 1968 edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, features an article about racism and racial identity amongst Mexican-Americans. The Lumberjack interviewed Hispanic faculty members and students to get perspective on their experiences as Mexican-Americans in the late 1960s. A local teacher asserted that racial tensions began with the first Mexican migrant workers who did not speak English or assimilate to Anglo-American culture. One NAU student, Margaret Valdez, further explained the development of a Mexican-American inferiority complex that developed amongst first generation Mexican-Americans whose parents immigrated to the United States as farm laborers.

The Lumberjack, October 22, 1968. This 1968 edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, features an article about racism and racial identity amongst Mexican-Americans. The Lumberjack interviewed Hispanic faculty members and students to get perspective on their experiences as Mexican-Americans in the late 1960s. A local teacher asserted that racial tensions began with the first Mexican migrant workers who did not speak English or assimilate to Anglo-American culture. One NAU student, Margaret Valdez, further explained the development of a Mexican-American inferiority complex that developed amongst first generation Mexican-Americans whose parents immigrated to the United States as farm laborers. The Lumberjack, April 5, 2007. This 2007 edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, covered the third annual Cesar Chavez march in Flagstaff, Arizona. The article provides insight into some of the important reforms that the United Farm Workers association secured for migrant farm workers in the American Southwest, including better wages and working conditions. Participants praised the UFW’s leaders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta for their political activism which was responsible for such reforms. They carried posters bearing the UFW’s symbol, pictures of Cesar Chavez, and other symbols from the Civil Rights movement such as the raised fist. NAU’s Hispanic student organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A), founded the annual march in April of 2005. Subsequent marches, like this one from 2007, brought Flagstaff’s Hispanic population together to celebrate their heritage and cultural icons.

The Lumberjack, April 5, 2007. This 2007 edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, covered the third annual Cesar Chavez march in Flagstaff, Arizona. The article provides insight into some of the important reforms that the United Farm Workers association secured for migrant farm workers in the American Southwest, including better wages and working conditions. Participants praised the UFW’s leaders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta for their political activism which was responsible for such reforms. They carried posters bearing the UFW’s symbol, pictures of Cesar Chavez, and other symbols from the Civil Rights movement such as the raised fist. NAU’s Hispanic student organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A), founded the annual march in April of 2005. Subsequent marches, like this one from 2007, brought Flagstaff’s Hispanic population together to celebrate their heritage and cultural icons. The Lumberjack, April 14, 2005. This edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, features an article about the first annual Cesar Chavez march in April of 2005. The march was organized by a Hispanic student organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A), at NAU to honor the memory of the United Farm Workers’ leader. M.E.Ch.A hoped to raise awareness about the important role that Cesar Chavez played in the fight for Hispanic migrant workers’ rights as well as his influence on the overall Chicano population of the United States. The march started at the first Chicano church in Flagstaff, Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, and continued on through the city of Flagstaff, Arizona.

The Lumberjack, April 14, 2005. This edition of Northern Arizona University’s student-run newspaper, The Lumberjack, features an article about the first annual Cesar Chavez march in April of 2005. The march was organized by a Hispanic student organization, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicana/o de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A), at NAU to honor the memory of the United Farm Workers’ leader. M.E.Ch.A hoped to raise awareness about the important role that Cesar Chavez played in the fight for Hispanic migrant workers’ rights as well as his influence on the overall Chicano population of the United States. The march started at the first Chicano church in Flagstaff, Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, and continued on through the city of Flagstaff, Arizona. Couple with Woman Wearing Sombrero with UFW Symbol When the Bracero Program ended in 1964, many farms turned to prisons in the Southwest for another source of cheap labor. Mexican Americans, who were widely incarcerated due to racial profiling by the police and border patrol, once again found their labor exploited by big agricultural farms. As late as 1978, prisons used Mexican American prisoners to pick cotton for no pay. Strikes and protests were rare in these prisons, but those that emerged drew inspiration from the United Farm Workers’ movement of the early 1960s to advocate for shorter work weeks and better working conditions. This drawing captures the connection between labor activism in the prisons and the farmworkers movement. The artist depicts a guard tower and a cell to represent prison laborers with a woman in the foreground wearing a sombrero that bears the United Farm Workers’ symbol.

Couple with Woman Wearing Sombrero with UFW Symbol When the Bracero Program ended in 1964, many farms turned to prisons in the Southwest for another source of cheap labor. Mexican Americans, who were widely incarcerated due to racial profiling by the police and border patrol, once again found their labor exploited by big agricultural farms. As late as 1978, prisons used Mexican American prisoners to pick cotton for no pay. Strikes and protests were rare in these prisons, but those that emerged drew inspiration from the United Farm Workers’ movement of the early 1960s to advocate for shorter work weeks and better working conditions. This drawing captures the connection between labor activism in the prisons and the farmworkers movement. The artist depicts a guard tower and a cell to represent prison laborers with a woman in the foreground wearing a sombrero that bears the United Farm Workers’ symbol. César Chávez’s Union Jacket This jacket was worn by Cesar Chavez who founded the United Farm Workers movement in 1962. Chavez and his associates dedicated their lives to improving the working and living conditions of Hispanic migrant farm workers in the United States. The United Farm Workers utilized boycotts and strikes, popular methods of political resistance in the 1960s, to communicate their demands to individual farmers and the American public. Cesar Chavez also drew on other tactics used by his political inspirations, such as Mahatma Gandhi, and partook in hunger strikes to encourage farmers to listen to the pleas of the farmworkers. Chavez remained politically active up to his death in 1993. Former President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded Cesar Chavez the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994.

César Chávez’s Union Jacket This jacket was worn by Cesar Chavez who founded the United Farm Workers movement in 1962. Chavez and his associates dedicated their lives to improving the working and living conditions of Hispanic migrant farm workers in the United States. The United Farm Workers utilized boycotts and strikes, popular methods of political resistance in the 1960s, to communicate their demands to individual farmers and the American public. Cesar Chavez also drew on other tactics used by his political inspirations, such as Mahatma Gandhi, and partook in hunger strikes to encourage farmers to listen to the pleas of the farmworkers. Chavez remained politically active up to his death in 1993. Former President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded Cesar Chavez the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994. ¡Huelga!: The Plight of Farmworkers This clip from Skeets McGrew’s 1965 film ¡Huelga! captures the living conditions of migrant farm workers in Delano, California. In this section of McGrew’s documentary, farm owners shared their opinions on the strikes and responded to the demands of the workers with little sympathy. The leadership of the United Farm Workers, which included Cesar Chavez, produced this film to highlight the plight of migrant workers and encourage Americans across the country to support their boycott of Delano grapes.

¡Huelga!: The Plight of Farmworkers This clip from Skeets McGrew’s 1965 film ¡Huelga! captures the living conditions of migrant farm workers in Delano, California. In this section of McGrew’s documentary, farm owners shared their opinions on the strikes and responded to the demands of the workers with little sympathy. The leadership of the United Farm Workers, which included Cesar Chavez, produced this film to highlight the plight of migrant workers and encourage Americans across the country to support their boycott of Delano grapes. Huelguistas: Delano Grape Strikers Oral History 1965, Maria Saludado A migrant farmworker and member of the Delano Grape Strike of 1965, Maria Saludado, recounts her experiences immigrating to the United States in the 1950s and working in American fields for ten cents an hour. She details the struggles of growing up in Chula Vista and San Diego, California from her attempts to get along with her Anglo American peers to the backbreaking labor that she and her entire family experienced in the fields. Saludado also details the health problems she contracted, such as asthma, from the pesticides used in the fields where she worked. Her story highlights the experiences of Mexican migrant workers in Delano during the 1950s and 60s, exploring the many issues they faced like low wages, health hazards, poor working and living conditions, and racial discrimination.

Huelguistas: Delano Grape Strikers Oral History 1965, Maria Saludado A migrant farmworker and member of the Delano Grape Strike of 1965, Maria Saludado, recounts her experiences immigrating to the United States in the 1950s and working in American fields for ten cents an hour. She details the struggles of growing up in Chula Vista and San Diego, California from her attempts to get along with her Anglo American peers to the backbreaking labor that she and her entire family experienced in the fields. Saludado also details the health problems she contracted, such as asthma, from the pesticides used in the fields where she worked. Her story highlights the experiences of Mexican migrant workers in Delano during the 1950s and 60s, exploring the many issues they faced like low wages, health hazards, poor working and living conditions, and racial discrimination. Pesticides Kill Farmworkers—1990 Cesar Chavez, a leader of the United Farmworkers Movement, discusses the health concerns of using the pesticide DDT in the fields. Chavez details the boycott of 1965 which urged grape growers to eliminate their use of pesticides because of farmworkers who developed cancer, experienced birth defects, and other health issues after exposure to DDT. He also explores the emergence of cancer clusters due to pesticide use in vineyards and other agricultural sites in the Silicon Valley of California. Chavez recounts the success of the 1965 boycott and uses it as motivation for farmworkers in the 1990s to take up the fight against another deadly pesticide, organophosphates.

Pesticides Kill Farmworkers—1990 Cesar Chavez, a leader of the United Farmworkers Movement, discusses the health concerns of using the pesticide DDT in the fields. Chavez details the boycott of 1965 which urged grape growers to eliminate their use of pesticides because of farmworkers who developed cancer, experienced birth defects, and other health issues after exposure to DDT. He also explores the emergence of cancer clusters due to pesticide use in vineyards and other agricultural sites in the Silicon Valley of California. Chavez recounts the success of the 1965 boycott and uses it as motivation for farmworkers in the 1990s to take up the fight against another deadly pesticide, organophosphates. Paul Taylor with Migrant Workers, Imperial Valley, California Dorothea Lange’s husband, Paul Taylor, stands with a family of migrant farm workers in California. Taylor was a professor of economics and became interested in the plight of Mexican migrant workers after receiving his PhD in Labor Economics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1922. Lange took this photograph early in her relationship with Taylor during a trip in 1935 to document the lives of farm workers throughout California. It displays the poor living conditions of workers who toiled in the fields for very little money. The couple used photography to highlight the struggles that migrant workers faced and encourage political action to improve their living conditions.

Paul Taylor with Migrant Workers, Imperial Valley, California Dorothea Lange’s husband, Paul Taylor, stands with a family of migrant farm workers in California. Taylor was a professor of economics and became interested in the plight of Mexican migrant workers after receiving his PhD in Labor Economics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1922. Lange took this photograph early in her relationship with Taylor during a trip in 1935 to document the lives of farm workers throughout California. It displays the poor living conditions of workers who toiled in the fields for very little money. The couple used photography to highlight the struggles that migrant workers faced and encourage political action to improve their living conditions. Farm Workers, South of Tracy, California Two farm workers, a couple, carry produce on their shoulders in the hot California sun. The weight of their produce was then used to determine their payment as part of the migrant worker program. The Farm Security Administration commissioned Dorothea Lange in 1938 to visit such farms in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia, Missouri, and California. Lange used her photography to advocate for better working conditions for migrant workers after witnessing their plight in the workers’ camps.

Farm Workers, South of Tracy, California Two farm workers, a couple, carry produce on their shoulders in the hot California sun. The weight of their produce was then used to determine their payment as part of the migrant worker program. The Farm Security Administration commissioned Dorothea Lange in 1938 to visit such farms in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia, Missouri, and California. Lange used her photography to advocate for better working conditions for migrant workers after witnessing their plight in the workers’ camps.