Prima Donnas Challenging Operatic Exclusions

At the intersection of identities such as gender and race, prima donnas received even more attention and critique from the public, further highlighting the subversive potential that the prima donna avenue provided for women and the increased barriers that they faced.

As a historically exclusionary and elite performing art, singers from Ángela Peralta to later nineteenth and early twentieth century stars like Sissieretta Jones, Marian Anderson, and Denyce Graves faced additional barriers in becoming prima donnas. Despite these obstacles, they were able to accomplish major feats as well in establishing their vocal prowess on operatic stages.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, prima donna Sissieretta Jones challenged an exclusionary profession and faced challenges like undesired comparisons. Pictured below in an albumen silver print portrait wearing a variety of medals, Jones, a classically trained soprano, was the highest earning Black performer during her age.

She was also compared to singers like Adelina Patti, where the media frequently referred to her as “Black Patti” in a constant comparison rather than calling her by her real name much to her discontent, highlighting the additional scrutiny that marginalized women faced in the field. Despite these challenges, she displayed her talent in events like singing for presidents and royalty, and went on to found her own performance troupe that enjoyed popularity in the U.S. and Canada.

By the mid-twentieth century in 1955, renowned contralto Marian Anderson became the first Black soloist to debut at the Metropolitan Opera, which had previously been “exclusively white for its entire seventy-two-year history,” according to scholar Nina Sun Eidsheim (2011, p. 641). Yet, despite her immense vocal talents, she too faced critique and racist challenges, not only from elite white men but also from elite white women, where the Daughters of the American Revolution attempted to bar Anderson from singing in their Constitution Hall in 1939 because of her skin color.

This exclusion resulted in organizations like the NAACP organizing against the D.C. Board of Education, who refused Anderson the opportunity to use an auditorium at a white high school, and the resignation of D.A.R. members like Eleanor Roosevelt in protest. In response, Anderson instead gave an outdoor concert at the Lincoln Memorial to a crowd of over 75,000 people, opening her performance by singing "My Country 'Tis of Thee."

A dress both she and Denyce Graves later wore featured below in its silky pale bronze reflects the craftsmanship of designer Barbara Karinska and Anderson’s prominence as she impacted a legacy of marginalized performers who could pursue their passion in the opera.

“Ego’s Absolutely Necessary:” Embracing the Prima Donna Title

By the twenty-first century, opera and the gossip surrounding its stars has waned in widespread popularity, where prima donnas like Denyce Graves have become more appreciated for their vocal skills than the events of their private lives. Pictured below, Graves performed in lead roles like Carmen from Bizet’s opera of the same name, wearing an extravagant dress comprised of a silk satin corset with beaded sleeves, and a skirt of pink ruffles in taffeta with a black velvet skirt mirroring Andalusian flamenco dresses.

Yet, the term “prima donna” as a pejorative has not died. In fact, it has migrated into everyday use. Outside of operatic circles to this day, some have deemed “difficult” or over-dramatic working women in the public eye as prima donnas or divas, erasing their original meanings as highly skilled performing artists in favor of its cattier current popular definition.

In an April 2023 interview with the New York Times, Denyce Graves, asserted that as an opera singer, “Ego’s absolutely necessary" (para. 1). Not only describing the need for self-possession as an opera singer, she also discusses how her identity as a Black woman has influenced her emphasis on growing vocal skill that cannot be denied.

Maria Callas, a legendary soprano of the twentieth century known for her bel canto style, also emphasized her intentions—typically perceived as difficult—as assertive and professional choices. In a 1959 interview with LIFE, “I am Not Guilty of All Those Callas Scandals,” she explains her true feelings surrounding scandals that she constantly faced as the media dubbed her a tigress.

Callas (1959) emphasizes that she does not enjoy justifying her actions, but asserts that: “if music is treated in a shabby or second-best way, I do not want to be associated with it…I especially do not want to give an inferior performance myself" (p. 118).

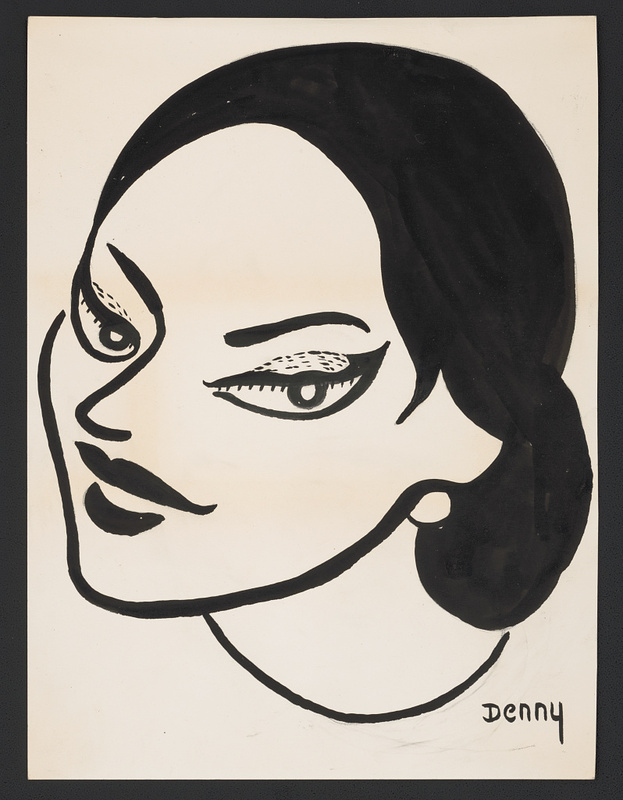

Indeed, she clearly outlines her passion for performance and music and her goals to put on performances with a professional integrity that she can be proud of. A painting of her by Diana Denny captures her assertive identity as she looks to the viewer with a driven smile, complete with bold lipstick and sparkling eye-shadow. Thus, prima donnas, despite negative associations for which the term came to be known, have embraced their identities as the first ladies of the opera.