Prima Donnas' Private Lives: Gossip and Rumor in Eighteenth Century Opera

Early Eighteenth-Century Celebrity and Critique

By the early eighteenth century, opera had spread throughout Europe and found itself entertaining the continent’s royal courts. Prima donna Faustina Bordoni was one woman who possessed both immense professional talent and a highly publicized private life filled with alleged rivalries and love affairs. Bordoni performed frequently for the Saxon court under Augustus II, where they particularly praised her for her skillful coloraturas.

Yet, her abilities were often framed within a rivalry between her and fellow prima donna Francesca Cuzzoni that was perceived in eighteenth-century pamphlets as a catty, jealousy-filled relationship according to scholar Suzanne Aspden’s “the 'Rival Queans.'”

Highlighted below, the Satirical Print of Cuzzoni, Farinelli, and Heidegger depicts Bordoni’s alleged prima donna foe. In this highly satirical etching, Francesca Cuzzoni is portrayed on the work’s left-hand side, looking upturned at tall fellow opera singer Farinelli. In the text below, Heidegger speaks to the pair about the declining popular state of the opera in favor of balls, calling her a “warbling bird” who had “no shelter” for her notes.

In similarly critical works, Bordoni’s private life also became inseparably tied to her public stardom as an affair between her and a Mr. Fuchs was satirized by the prominent Meissen sculptor Johann Joachim Kändler in Faustina Bordoni and Fox pictured below. This c. 1743 hard-paste porcelain figure features Bordoni, dressed in luxurious jewel tones singing effortlessly across from the fox representing Mr. Fuchs. The fox is also depicted as playing a piece from an opera written by Bordoni’s husband, Johann Adolf Hasse.

The Meissen manufactory comprised the first porcelain artisans who could recreate the hard-paste porcelain popular in areas like China and Japan in the late seventeenth century. The material, also known as “true porcelain,” originated in China and was notoriously difficult to replicate as the particulars of its recipe were unknown in Europe until the re-creation of the formula using quartz, feldspar, and kaolin clay. The medium, as can be seen in Faustina Bordoni and Fox, resulted in glassy, near-transparent figures that retained their shape in greater detail due to the kaolin clay’s ability to withstand higher firing temperatures.

The fox and the piece that he is playing are highly intentional in their reference to the affair and thus display the increasing attention and critique that was paid to prima donnas’ private lives rather than solely focusing on their professional skills. Together, these pieces display the beginnings of prima donnas as the receivers of negative personal criticism.

Opera: A Social Event

As demonstrated by its attention—whether positive or negative—attending the opera had become a social event by the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, and represented an elite opportunity for nobles and society to mingle among each other while listening to expert singers during the century. The Gloves (Likely French), c. 1735, represent one of the lavish peices with which spectators adorned themselves.

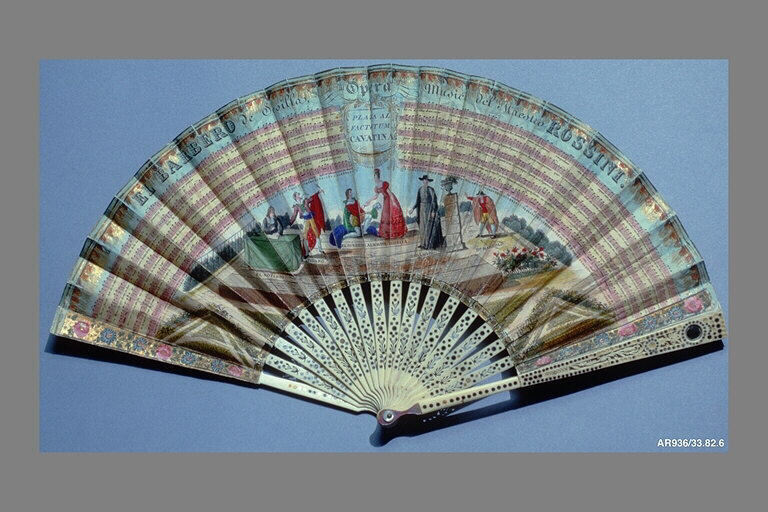

Attending the opera was a time to make fashion statements. For women, opera gloves were often long with detailed designs to show off. The gloves below feature a mix of leather and silk materials with ornate gold detailing that suit a night out at a high society event like the opera. Other items that people commonly brought included opera glasses and fans, such as the one featured below with a design from Rossini's Barber of Seville designed by the French Fernando Coustellier and Co. Like gloves, these dual-purpose items provided both relief from the heat of the theater and acted as a fashion accessory.