Venus and Her Potency

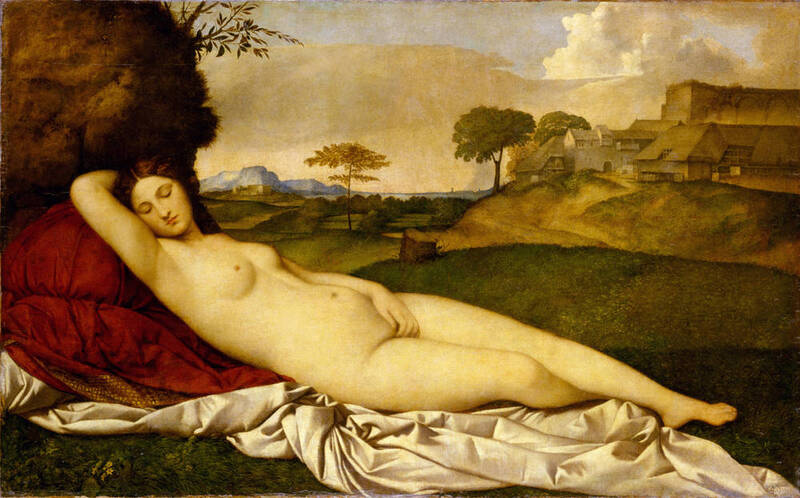

Venus in ancient Roman mythology ruled over marriage, love, sexuality, and beauty. In Titian’s Venus of Urbino, her relaxed posture and delicately placed left hand, just covering her pelvic area, suggests that Venus is at ease in her vulnerability, her posture open and comfortable. Her intense gaze yet soft expression seducing the viewer as well. Everything about Venus in this portrait demonstrates the emotions that the goddess controls. Symbols associated with Venus are also included, specifically the flowers clutched in her right hand and the small, sleeping dog at the foot of the lounge she lays on. The second work, Slumbering Venus (right), is thought to have been finished after the death of its artist, Giorgione, by Titian. This is evident as the poses of each Venus are nearly identical, with only the alertness being changed. However, Giorgione’s Venus feels more romantic, with the goddess’s eyes closed and expression plain, sleeping in an open field that gives the impression of isolation.

Other artists favored bringing to life the myths of Venus with her mortal lover, Adonis, or her divine partner, Mars, god of war. These depictions find balance in explicit erotica and romantic themes. Artists like Titian fostered this multifaceted nature of the goddess. In his Venus and Adonis, Venus’s nudity has nearly nothing to do with the scene. Her lack of attire rather calls to the humanist value of imitating the technique of the ancients regarding the human form. Like Jupiter and Apollo, an underlying theme of her paintings is power. Venus and Adonis illustrates the scene prior to Adonis’s death. Venus begs for him to not leave her, clinging to his shoulders in a vain attempt at stilling his movement. Bronzino’s An Allegory of Venus and Cupid also exemplifies power struggles involving Venus. She and cupid embrace in quite an erotic way; however, both have different motives. Cupid gropes the goddess as a method of diversion for the viewer and Venus, so one does not notice him stealing her diadem. Venus is not innocent, as she leans up to kiss the boy, distracting him from the theft of his arrows.

Venus in the Baroque period did not change much thematically. The two pieces, Peter Paul Reubens (1577-1640) Venus and Adonis and Annibale Caracci’s (1560-1609) Venus, Adonis and Cupid demonstrate that myths about Venus did not ebb and flow, confirming her popularity as a subject. However, what did change happened to be the dramatic realism of the paintings. Reubens and Caracci utilize dramatic lighting to emphasize Venus’s romantic figure and her desperation for her lover to not leave her side. The artists also enhance Venus’s figure, using shadows to soften her curves, employing that humanist style as well.