Contributions to Archaeology

Jean Dieulafoy

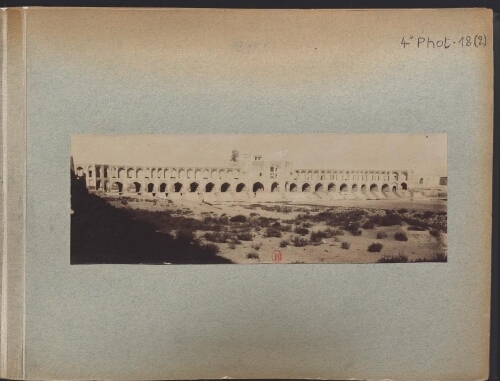

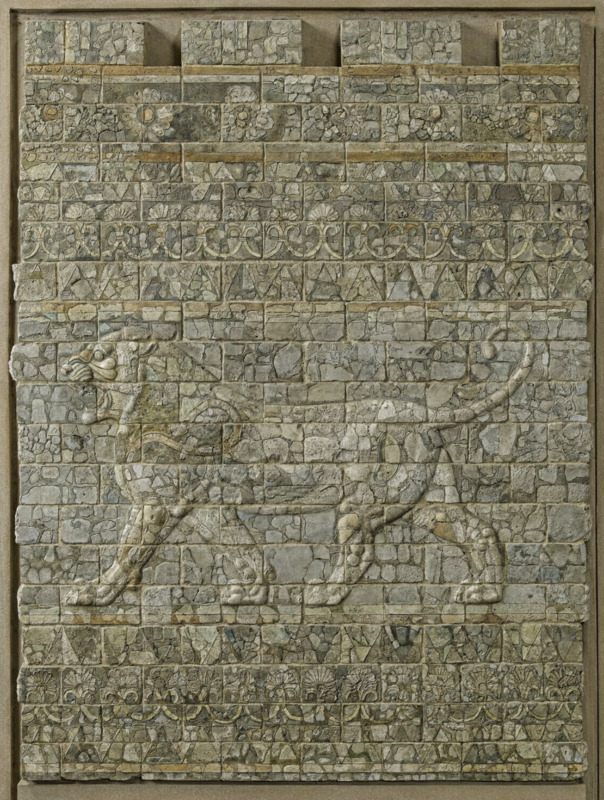

Jean wanted “to take part in archaeology as her husband’s collaborateur, with the masculine ending of the word” (Arwill-Nordbladh 143) instead of her name being erased from their work, so she became a field archaeologist. Her responsibilities included “all the photographic work, the direction of several sites and holding the excavation’s log book” (Gran-Aymerich). This was quite a bit of responsibility. Their work, funded by the Louvre, was focused on the two ancient cities of Persepolis and Susa in Persia. Figures 12 and 13 show pictures of buildings and people that Jean took during her work there. Jean took many pictures in Persia and it is really amazing to have so many examples of the people and places and things she saw. While at the city of Susa between 1884 and 1886, Jean systematically excavated two friezes, which are now on display in the Louvre. Figure 14 is an image from the Louvre depicting the Archers Frieze and Figure 15 is an image of the Lion Frieze that Jean excavated. These brick panels are ornately detailed with geometric patterns and they would have proved very difficult to excavate and return in one piece.

These friezes were a beautiful and important discovery, and their careful excavation added to her skill set. Jean’s work during their excavations was impressive to many people. She found a way to capture the work and the world through pictures, drawings, and writing. She wrote impactful stories and knowledgeable reports. In my opinion, she added to the part of archaeology that many of us are invested in today, which is understanding and appreciating the context of your research and sharing it. It is truly essential that we have the information that she recorded.

She wrote about their excavations in Susa:

“Full of emotion, I struck the first blow with the pick on the Achaemenidaean tumulus, and worked until my strength gave out. My husband then took his turn with the pick, while our acolytes carried away the loose earth. This was how the excavations at Susa were begun" (Dyson 26).

Maud Cunnington

Maud and her husband worked at Woodhenge between 1926 and 1929. From the site, they found “six concentric ovals of standing posts … which were built to align with the summer solstice sunrise” (English Heritage). The Cunningtons replaced the locations of the timber posts with ceramic pillars to represent where the posts would have stood, bought the land, named it Woodhenge because of its relation to the nearby site of Stonehenge, and opened it up to the public. From Woodhenge, Maud excavated pottery, animal bones, human bones, tools, and two human burials.

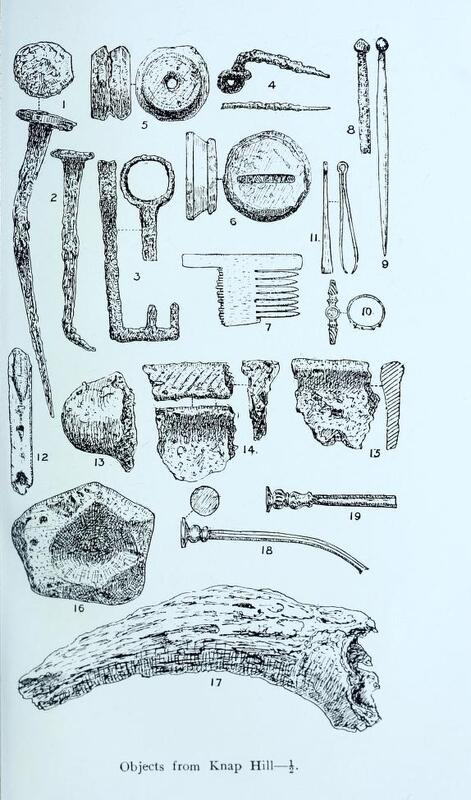

Her main work in the partnership was to oversee the excavations and to write the archaeological reports in journals, articles, and books. She also took time to hold public speeches and forums to share her work. Similar to Dieulafoy, she illustrated her work in the form of maps and drawings, such as some artifacts from her excavations from Knap Hill in Figure 16. Because Maud published her work so openly, she made archaeology at the time more accessible and aided in public awareness of history and archaeology. Additionally, by contributing Woodhenge to the public, the Cunningtons made history available for everyday people to see.

Jacquetta Hawkes

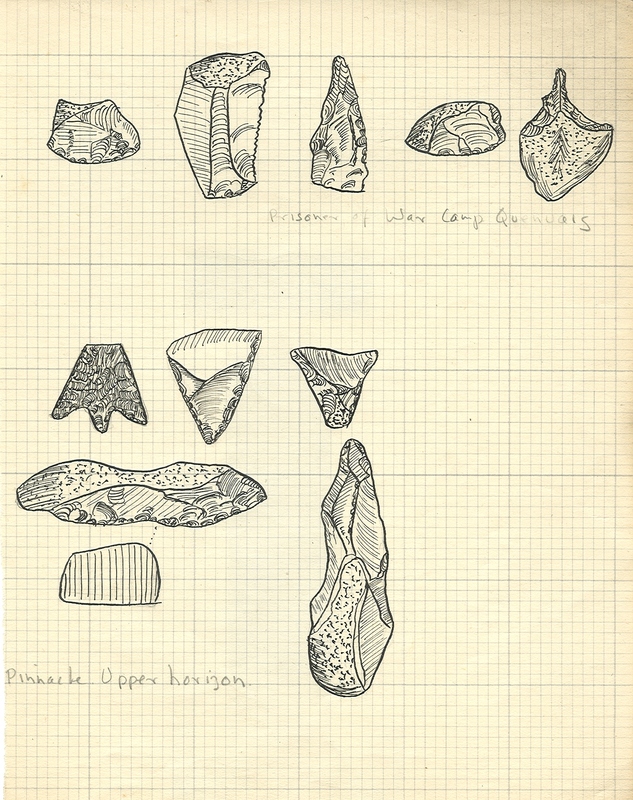

Jacquetta went on to supervise and participate in multiple excavations in Palestine, the Channel Islands, Ireland, and more. In Palestine, Jacquetta was exhilarated to participate in the excavation of a Neanderthal skeleton in 1932. Jacquetta was described as feeling very emotional at this dig, as it was her first big dig and because she felt “a strange kinship with this ancestral figure whose fragile skull she held” (Special Collections at the University of Bradford Jacquetta Hawkes). Jacquetta also illustrated her work, a similarity that all three women in this exhibit share. Many of her illustrations included artifacts and objects from her excavations, like the flint stones seen in Figure 17. These flint stones are likely examples of stones that had been chipped to form tools and weapons and the remaining stones that had pieces chipped away.

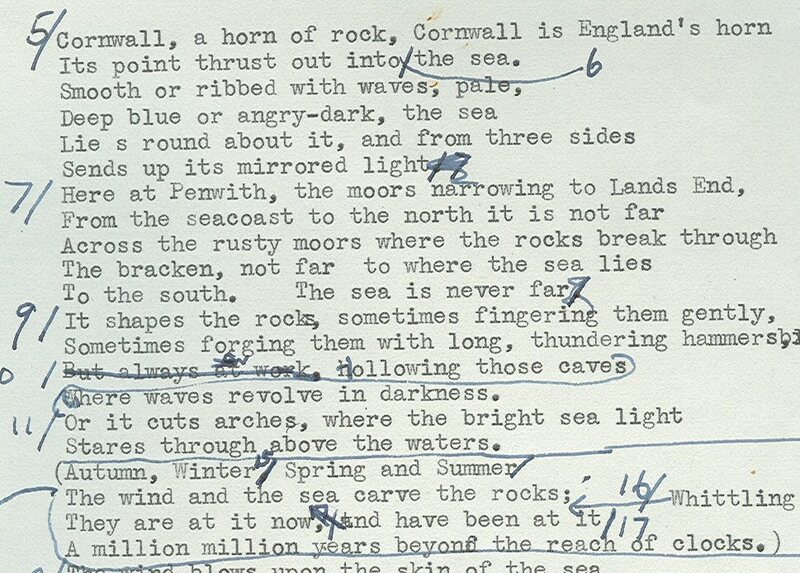

Unlike some who believed that women should stay home after having a child, Jacquetta continued to work and became a Principal and Secretary for the UK National Committee for Unesco until 1949. After she married J.B. Priestley, she began her creative career as a novelist, poet, and playwright. Figure 18 is an example of a draft of her work in film making. The film, titled "Figures in a Landscape", is about the work of a sculptor named Barbara Hepworth. On top of this, she published many educational books including The Archaeology of the Channel Islands, Guide to the Prehistoric and Roman Monuments in England and Wales, Early Britain, The Atlas of Early Man, and more.