Sexism and Homophobia in Archaeology

Women became involved in archaeology during the nineteenth century, even though they were expected to be in the home during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was not lady-like to have a job in a field dominated by men and “manly” things such as wearing pants, working outdoors, using tools and weapons, experiencing harsh weather conditions, and participating in physical labor. Because of the roots that homophobia had in cultures around the world, if women were as smart as men, participated in "man-like" behaviors, and were not staying in the home, then they were often considered to be lesbians.

This judgement likely kept numerous women out of archaeology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For a woman to prosper in archaeology took skill and bravery, especially because it was such a male dominated field. However, white women have only moved the bar so far. Incorporating women into archaeology is a step, but people of color and the queer community have had to work even harder to be included.

Jean Dieulafoy

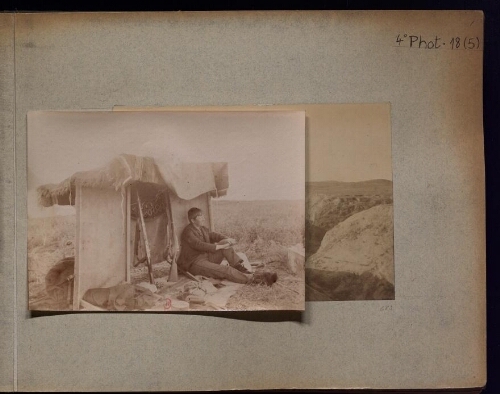

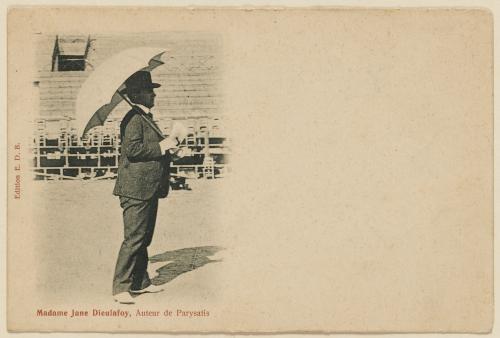

Dieulafoy was very prominent in archaeology because of the way she expressed her gender. Dieulafoy had short hair, wore suits made for men, and acted “manly”. Figures 8 shows Dieulafoy wearing one of these men's suits and posing for a picture in Persia during one of her travels. Figure 9 depicts Dieulafoy wearing her treademark suit and a tophat while holding onto an umbrella. In modern times, her self-expression might be considered an example of transgender expression, but she never directly commented on her self-image. She did not identify as a “New Woman” who was seen rejecting all femininity or a “femme moderne” who was a woman balancing femininity, family, and career. She did not participate in the feminist movement at the time and did not argue for women’s rights. Jean argued for her own rights and created her own unique mode of gender expression.

During Jean's life, it was illegal for women to wear pants in public in France, because of an ordinance passed in 1800. After her travels in 1886, the government granted Jean a “permission de travestissement” or a "cross-dressing permit" which allowed her to wear suits. It is amazing to see how far we have come now that women do not have to wear pants to be taken seriously, but it does not mean that that mentality is completely gone. Dieulafoy and her husband collaborated on every project they worked on together. This was one of the few examples at the time of a relationship where the wife was recognized as well as the husband, which could be because France actually encouraged marriage partners to work together.

Because it helped Jean to present as a man during her time in the war, she continued to present as a man during her work abroad. The societal expectations of how men and women should act meant that it was easier for Dieulafoy to pursue her work while presenting as a man. A woman who portrayed her femininity would not have been taken seriously. Because of Jean's hair and clothes, there was speculation that she was lesbian, regardless of her marriage to a man. Instead of letting the judgements get to her, Dieulafoy adapted and continued to express herself in her own way.

Maud Cunnington

As a woman in British society at the time, Maud was expected to be “if not invisible, then certainly in the background” (Roberts 47). Some believe that Maud entered the field because of her dutiful interest in her husband’s work, but Maud had her own interests in her archaeological excavations. Her respect and passion for archaeology can be seen clearly throughout her work. Figure 10 is an example of the pottery that Maud excavated carefully to preserve the shape and surface of the vessel. This piece is from All Cannings Cross, like the other vessel sherds in Figure 6. Some coworkers described Maud to be terrible with bad methods, but there is little evidence to back this. This judgement could arise from a general societal distaste of a woman being as capable as a man and acting “man-like”.

She could have been looked down upon because she was a smart woman, which could have easily ruffled feathers. It is hard for a woman to be appreciated if she is not beautiful, but if she is beautiful then she is often not taken seriously. The world that Maud lived in gave women few rights. Women could be incarcerated against their will, legally beaten by their husbands and fathers, barred from attending university, not allowed to vote, and more. Maud had to navigate her work in that world and “while women may have been tolerated, they were not always welcomed” (Roberts 49).

Many archaeological societies did not allow women to join until later into Maud’s life, which excluded her from many opportunities, just because she was a woman. By keeping women out of clubs, it kept them in the dark. Maud was especially interested in sharing her work publicly, perhaps because she knew how it felt to be left out. She once told a fellow woman archaeologist to not join the field of archaeology because it was too difficult as a woman. Clearly, Maud was feeling the effects of her gender in her work.

Jacquetta Hawkes

Jacquetta had an impressive education for a woman at the time, considering the degree for archaeology was especially new. She pursued archaeology even though she likely received judgement for it at the time, considering it was a male-dominated field. Not only was she educated, but she had a way with words. Her books were detailed, educational, and comprehensive and her poems, plays, and films had a great impact. Jacquetta was described as having a masculine intellect, which arguably diminishes her intelligence. If it is a compliment to have masculine intellect, then it must not be good to have feminine intellect or to be smart, like a woman can be.

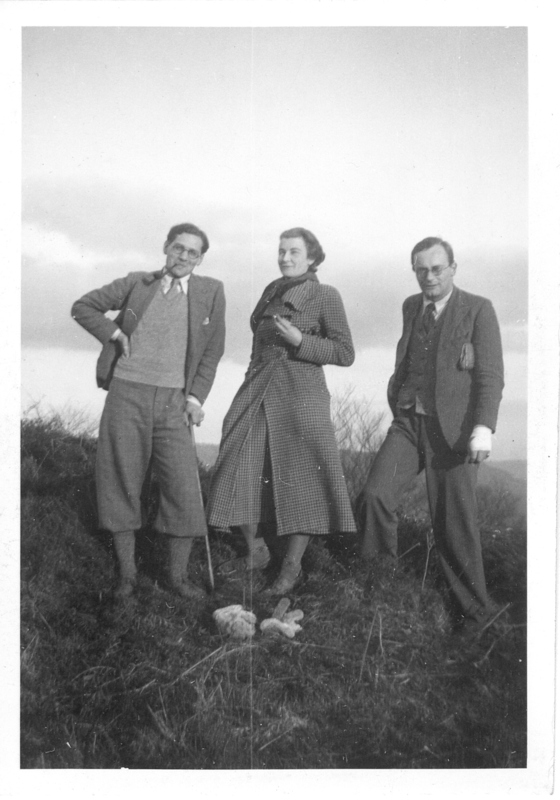

Jacquetta proved how smart women are, were, and can be. Regardless of being described as a beautiful young woman, as exemplified in Figure 11, who attracted many men, Jacquetta brought much more to her work. Just like with Maud, it is often difficult to separate famous women from being beautiful or not beautiful. It seems that it is a crime to not be beautiful and attracting men, but if you are beautiful and attract too many men, then that is a problem as well. It is sad to see such language describing a woman who contributed much to archaeology and to the lives of others.