Home Is (Not) My Body

While HIV has existed and afflicted humans as far back as the early 1900s, the AIDS Crisis did not truly begin until 1980, when the first group of gay men in New York were reported to have contracted the virus. These men would be the first of millions worldwide to die of HIV-AIDS, which afflicts regardless of gender, age, or sexuality. Initially considered a “gay cancer” by the general American public, the Reagan administration put little effort into funding medical research and allowed for the widespread deaths of queer people. It wasn’t until several years later, when constituents made clear that they would not support Reagan’s re-election, that he provided additional funding for research. By then, AIDS had already grown into an epidemic claiming hundreds of lives, most heavily hitting communities of gay men, Black and Hispanic people, and people living on the streets.

The AIDS Crisis entirely reshaped how queer people of the 80s and 90s perceived home. For a community that had grown accustomed to embracing physical contact as an act of resistance, misinformation about the ways in which AIDS spread discouraged many from touching in any way. Those who were hospitalized by the condition rarely returned home, and hospital beds became a new kind of home instead. Decades later, AIDS still claims the lives of those who cannot afford treatment, and its effects live on in a multitude of queer communities.

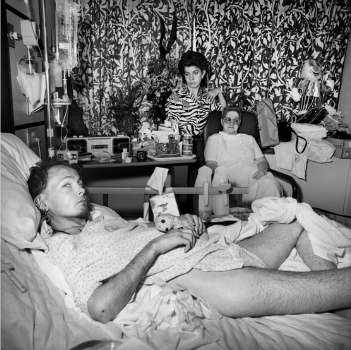

New York by Rosalind Fox Solomon

The three figures in this photo are unidentified by the artist and collecting institution. It is confirmed, however, that the man in the hospital bed is suffering from AIDS and being visited by the two people in the background. Despite his condition, the place has personality: his visitors’ expressive outfits, the animal print curtain in the background, even the small stuffed animal cradled in his arms. Through gifts and visitors, patients would attempt to add intention to the new homes imposed upon them. While this particular man’s story is lost to time, it is reassuring to see that he had those visitors despite the demonization of his disease and its effects.

Rosalind Fox Solomon first presented this image as part of her series, Portraits in the Time of AIDS 1987-1988. By the time she took these photos, AIDS had already become an epidemic, just as misinformation about the disease had as well. While some of her audience criticized her for combining documentary and fine art photography, Solomon breathed life into a series that was otherwise dominated by themes of decline and death.

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) by Felix Gonzalez-Torres

This is perhaps the most iconic piece of work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, a gay man who lost his partner, Ross Laycock to AIDS in 1991. First produced in the same year, Portrait of Ross in L.A. is just what it appears to be: a pile of candies on a gallery floor. Museum patrons are allowed to take a piece from the pile and employees are instructed to allow the pile to diminish until it is fully depleted, then replace it with a new pile of candies. Gonzalez-Torres was a firm believer in allowing his audience to interpret pieces as they wished, though he did provide an explanation for this piece. It represents the complicity of Americans in the AIDS crisis that took Ross from him, visitors taking from the candy pile just as Americans took from queer popular culture amidst mass deaths. It also speaks to Gonzalez-Torres’s only method of coping at the time, as he created and re-created images of Ross through whatever inanimate objects he had access to. In the Ross-shaped space that remained in his last few years of life, Gonzalez-Torres placed items from their home that replicated the impermanence of his partner’s life.

Untitled (March 5th #2) by Felix Gonzalez-Torres

On March 5, 1991, Ross Laycock died of complications associated with HIV-AIDS. His partner, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, was distraught and dove into his work, creating dozens of artworks in the months following Ross’s death. One such piece is March 5th #2, which features two lightbulbs dangling from white cords pinned to a gallery wall. The lights are to remain illuminated at all times and the bulbs replaced only once both have completely faded. As viewers, there is no way to avoid complicity, as one can only watch the lights fade. The nature of the installation is that one bulb always fades before the other, much like the lives of the artist and his partner. Five years after Ross’s death, Felix Gonzalez-Torres joined him, also due to complications with AIDS, further cementing the metaphor behind this piece.

AIDS quilt, Washington, D.C. by Carol M. Highsmith

In 1985, the AIDS Quilt Project began in San Francisco as a grassroots queer response to the apathy of the U.S. government. In just two years, the project gained international attention so strong that its original founders were able to collect and piece together hundreds of panels into one massive quilt. At a time when deaths caused by AIDS were reduced to numbers, the AIDS quilt provided names, faces, and stories of those who were lost and expressed the magnitude of the virus. In 1987 and 1988, the quilt was displayed at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., where visitors could walk between panels and connect with their lost loved ones.

The AIDS quilt was the largest piece of folk art ever created, and it represented a community-built home during a time of tragedy. Art can be central to queer expression, and this piece is no exception. It is a demonstration of grief, resilience, togetherness, and protest against an apathetic government.