Home Is My Loved One

While many envision home as a house, apartment, or other living space, there are plenty others who find home in their loved ones. This can be for a myriad of reasons: a lack of stable housing, disconnection from physical space, or simply finding comfort and safety in their partner. For queer people, home can often be more complex than the space they live in due to history with anti-LGBTQ+ family members, landlords, and realtors. Physical spaces may easily become loaded with reminders of the barriers to living authentically, so for some, home becomes a person instead.

Domesticity between queer partners has the potential to either reinforce heteronormative gender roles or reshape them. As partners renegotiate the responsibilities within their relationship, they confront centuries of expectations for couples that they consciously and unconsciously navigate. This is a powerful opportunity to determine how their relationship will function in the long-term and how their individual perspectives on the home will change.

For those that do have a private space to share with their partner, the ability to express their love freely is incredibly healing. As a community that has historically been marginalized for who they love, the chance to construct a home centered around that love can be revolutionary. Even if that space remains forever private, it is an act of resistance against an anti-queer society that can reshape one’s perspective on the definition of home.

About the Photographer

In 1993, Nancy Andrews had just recently realized that she was gay. Amidst the AIDS crisis, which had claimed the lives of many queer people across the United States, she had few gay elders to look up to. Seeking to find others she could relate to and discuss her newfound sexuality, Andrews traveled the country and photographed as many gay and lesbian people as were willing. In an age of commonplace homophobia, it was difficult to find people brave enough to expose their sexualities to the world, but she did find them. Andrews soon after published Family: A Portrait of Gay and Lesbian America, which consisted of black and white photographs paired with brief stories about the people depicted. The following photos on this page are all from this first book by Andrews, as are details about the lives of those pictured.

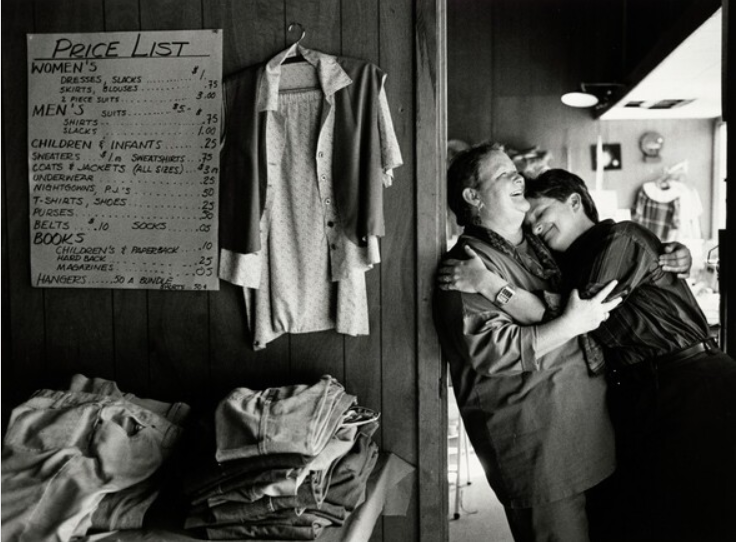

The Hensons

Brenda and Wanda Henson of Gulfport, Mississippi found home in each other, then made it their mission to provide a home for the lesbian community. The two women were disappointed in the minimal spaces available to lesbians, especially for feminist education and support networks. In response to this gap, they founded the Gulf Coast Women’s Festival, a food bank, and a secondhand store called Leftovers, where this photo was taken. When the Hensons first began Camp Sister Spirit, a live-in space for lesbians to connect, neighbors began harassing the couple with threats of violence and destruction of property. But the Hensons didn’t budge. Rather, they spoke with Oprah on live television about the discrimination they’d faced in their community and, with time, that community grew to accept and embrace their neighbors and their lesbian retreat. More importantly, their TV debut created a nationwide network of lesbians, just what they’d aimed to accomplish with their first food bank. Through Brenda and Wanda’s love for each other, they were able to create a home for hundreds of others and thousands more across the country.

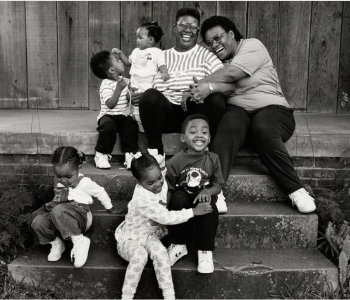

Nelita Williams and Barbara Hudson

Nelita Williams and Barbara Hudson of New Orleans, Louisiana have spent most of their lives caring for children. Before meeting, both had husbands and several children of their own, who they finished raising together. As their youngest children were getting close to adulthood and the women approached retirement, Nelita received a call that her oldest son had been arrested and that his five children would soon be put into foster care. She and Barbara fought for and won custody over Quinton, Kiana, Breana, Nelita, and Redius, who they began to raise as their own. Though their retirement was postponed once more, the couple’s home was revived with childlike joy and curiosity. This picture radiates with the love shared between them, with casual physical contact and nurturing embraces on the front steps of their porch.

"We're happy. We have a good relationship. We don't know what it's going to lead to with the children, but we're going to try our best to make them happy and keep them together." –Nelita Williams

Gean Harwood and Bruhs Mero

Gean Harwood and Bruhs Mero, who began as roommates in New York City, shared their first kiss on New Year’s Eve in 1929, then spent the rest of their lives together. Despite their romantic partnership, the two were forced to pose as roommates throughout their entire relationship to avoid discrimination by landlords. Living in the heart of the city, the two wrote showtunes for Broadway musicals together until Bruhs began to lose his memory to Alzheimer’s. In 1985, NYC Pride declared the two men Grand Marshals of the parade, an honor saved for queer elders. As the two grew older and Bruhs’ condition worsened, Gean could no longer care for Bruhs and reluctantly brought him to a nursing home, where this photo was taken. At the time of this photograph, Bruhs had little memory of his relationship with Gean. He would die a year later in 1995.

“There were times in our existence when there were some very strong pulls away from each other, but there was a continuity there that neither one of us could ignore, and somehow we seemed to be destined to be together. It’s very hard to put into words what that span of time really meant. I find it at this stage practically impossible to describe.” –Gean Harwood

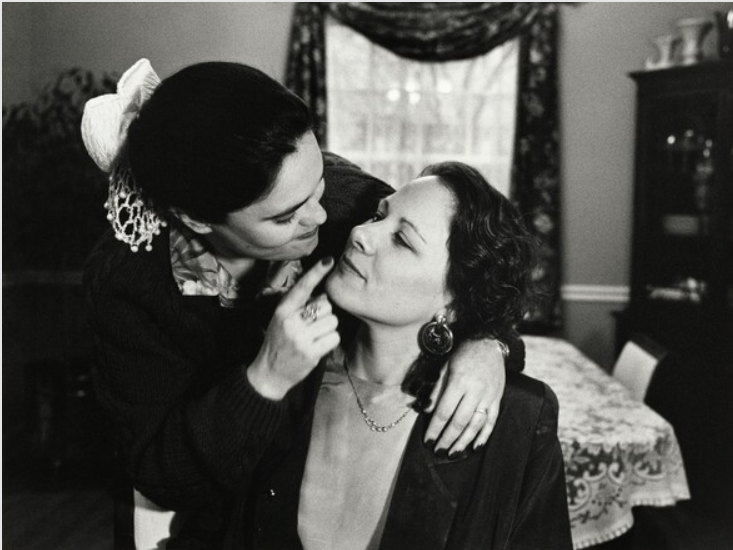

Phyllis Hunt and Terrie Harner

Phyllis Hunt and Terrie Harner of Arlington, Virginia also believed that they were destined to be together. Both members of the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches and firm believers in God, their love supported their faith and uplifted each other. In this photo, they share an intimate moment in their bedroom, a space of mutual understanding and comfort for the couple. Little is known of either woman today, though that's a part of the beauty of Nancy Andrews' narrative photography. Audiences are privileged to a glimpse of the lives of these everyday queer people in the 90's, but rarely will we hear how their stories end.

"It doesn't really matter if you're in a gay relationship or a straight relationship. Relationships take a lot of work and they take a lot of energy. And they take a lot of compromise." –Phyllis Hunt