A Home's Walls

At their simplest, walls serve two purposes: to keep some things in and others out. The walls of a home are no different. They provide shelter for those within, through both physical construction and metaphorical feelings of belonging, but they also prevent unwanted forces from entering. When we think of home as a space beyond the typical house, these walls continue still. Sometimes the walls are physical barriers to entry, but oftentimes they are visible only through the actions of others.

This section discusses three restrictions on queer home that come from both within and without the community. It is important to note that there are an abundance of barriers to queer home that are not discussed within this exhibit and that these are complex considerations that should be explored further.

Mama's Always Watching by D'Angelo Lovell Williams

D’Angelo Lovell Williams is a Black queer artist who explores the connections between physicality and identity, often doing so by involving family members in their work. In this photograph, Williams sits beside a portait of their mother, a common figure within their work. While in reality Williams and their mother have a positive relationship, this work depicts their struggle between sexuality and family expectations. Dressed in little clothing and posed with a hand creeping toward their crotch, Williams toes the line of indecency, all while sitting in a family armchair just below their mother’s portrait.

This piece is reminiscent of being closeted in a family home, wherein one must pit shelter and authenticity against each other. Young queer people without the resources to support themselves are faced with a decision between financial support and being treated as the person they are. That struggle can lead many to view their house as an antithesis to home and influence their perceptions of what a home should be.

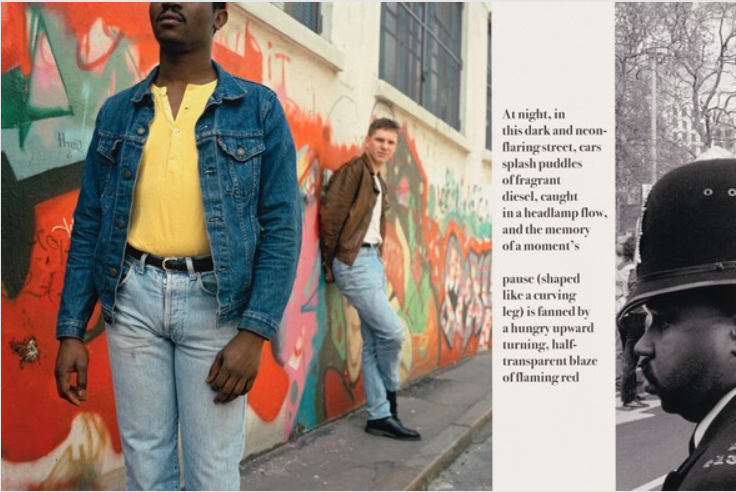

Untitled #2 by Sunil Gupta

Sunil Gupta’s Untitled #2 is an artistic rendition of his response to the UK’s Clause 28. During Margaret Thatcher’s leadership, the UK government refused to recognize gay couples as legitimate partnerships, denying their legal rights to be considered family and their shared living spaces to be considered family homes. This, paired with volatile behavior from homophobes in the region, led many gay couples to remain closeted in public spaces.

In this piece, Gupta pairs an image of a man admiring another man on the street with a photo of a law enforcement official at a demonstration against Clause 28. Sandwiched between these images is a poem written by Gupta’s former partner, Stephen Dodd, which is continued across several other pieces in the series. It reads:

"At night, in / this dark and neon- / flaring street, cars / splash puddles / of fragrant / diesel, caught / in a headlamp flow, / and the memory / of a moment's // pause (shaped / like a curving / leg) is fanned by / a hungry upward / turning, half- / transparent blaze / of flaming red."

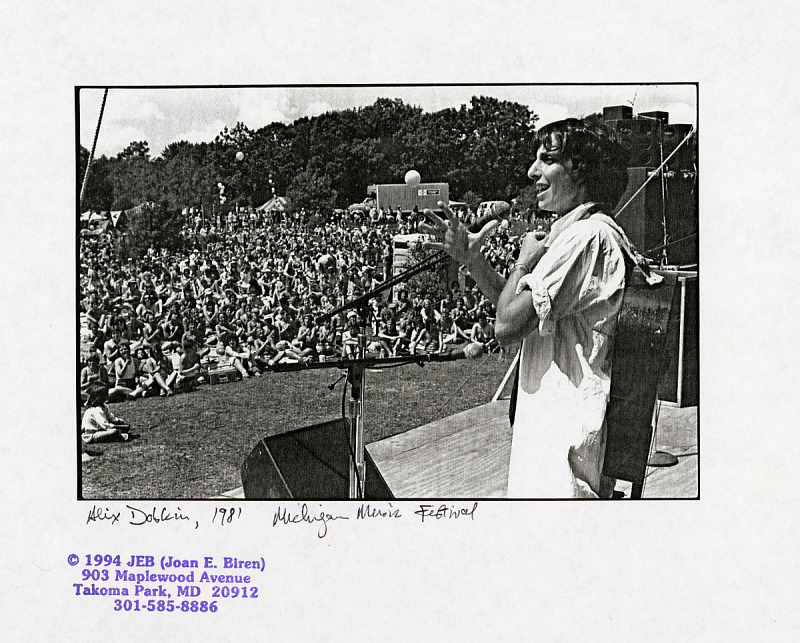

Michigan Womyn's Music Festival by Unknown

The 1981 Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival is one example of a barrier created from within the queer community. Marketed as an inclusive space for queer women, the festival drew hundreds of women from across the country for a weekend of music and community-building. When trans women arrived at the gates, however, they were turned away and told that only biological women were allowed to enter. This distinction, made in the name of women’s safety, was in reality a justification for invalidating the identities of other queer women. Transgender activists took great offense to the festival’s rules and protested just outside the premises of the event. While the festival did not adjust their judgment, their refusal to include trans women became central to historical records of the event.