Home Is Where I Live

When you picture home, what do you see? For most people, their first thought is of a house, so much so that they’ll begin to use the words “house” and “home” interchangeably. This is a perfectly reasonable thought process, as most houses are homes to the people that live within them. They provide shelter – a physical space of protection and comfort – as well as an emotional space of belonging.

For decades, queer and feminist scholars have argued that the traditional home is a site of reinforcing heteronormative gender roles. These roles are most visible in the division of domestic labor and chores, such as housecleaning for women and yardwork for men. These arbitrary gender-based rules of caring for the home uphold a lengthy history of women’s subjugation by men.

For many queer people, making a home provides an opportunity to complicate heteronormative gender roles. Without clear male and female individuals to fit into stereotypical boxes, queer partners can more easily renegotiate the household division of labor, as well as what a home looks like at all. The house also provides a physical space of privacy and protection from the outside world, an important consideration for a group that’s been historically oppressed for their intimate relationships. With a space to be oneself, the home is a revolutionary avenue for queer people to connect with their loved ones.

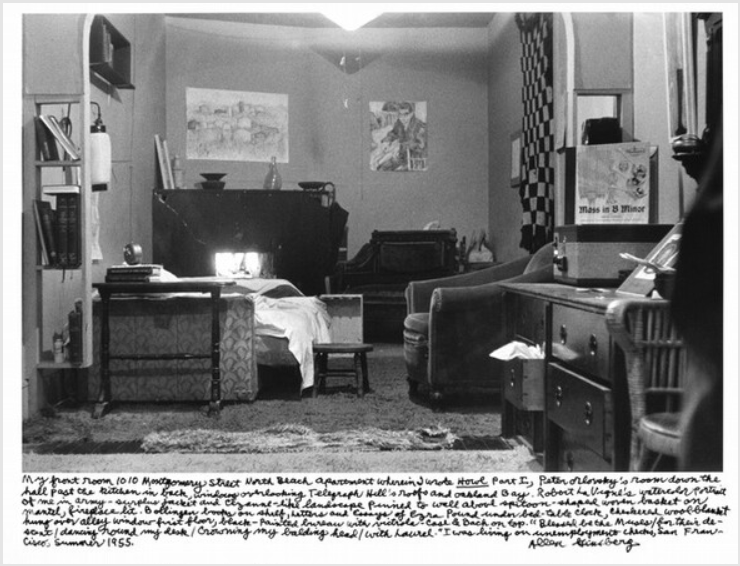

Untitled by Allen Ginsberg

"My front room 1010 Montgomery Street North Beach apartment wherein I wrote Howl Part I, Peter Orlovsky's room down the hall past the kitchen in back, windows overlooking Telegraph Hill's roofs and Oakland Bay. Robert La Vigne's watercolor portrait of me in army-surplus jacket and Cézanne-like landscape pinned to wall above spittoon-shaped woven basket on mantel, fireplace lit. Bollinger books on shelf, letters and Essays of Ezra Pound under bed-table clock, checkered wool blanket hung over alley window first floor, black-painted bureau with victrola-case & Bach on top. ‘Blessed be the Muses / for their descent / dancing round my desk / Crowning my balding head / With laurel.’ I was living on unemployment checks, San Francisco, Summer 1955."

Allen Ginsberg, who took this photo and wrote its caption, was a prominent poet and author throughout the 1950s-1970s, during which he openly expressed his homosexuality. But does this bedroom look queer to you? Could you tell that Allen Ginsberg was gay just from this photo’s caption? Probably not! That’s the beauty of it: The queer home is just as much a home as any other. This is an intimately messy photograph – the bed unmade, an open drawer, the overhead lighting casting a bright reflection across Ginsberg’s headboard – a true representation of his apartment. He’s honest in his caption of which books and paintings are present, even going so far as to list his address. But could you tell that Peter Orlovsky is his lover? Likely not without some additional research. The mundanity of this photograph normalizes the queer home as an ordinary space, serving as a sort of justification to homophobes that queer people can exist in ordinary ways.

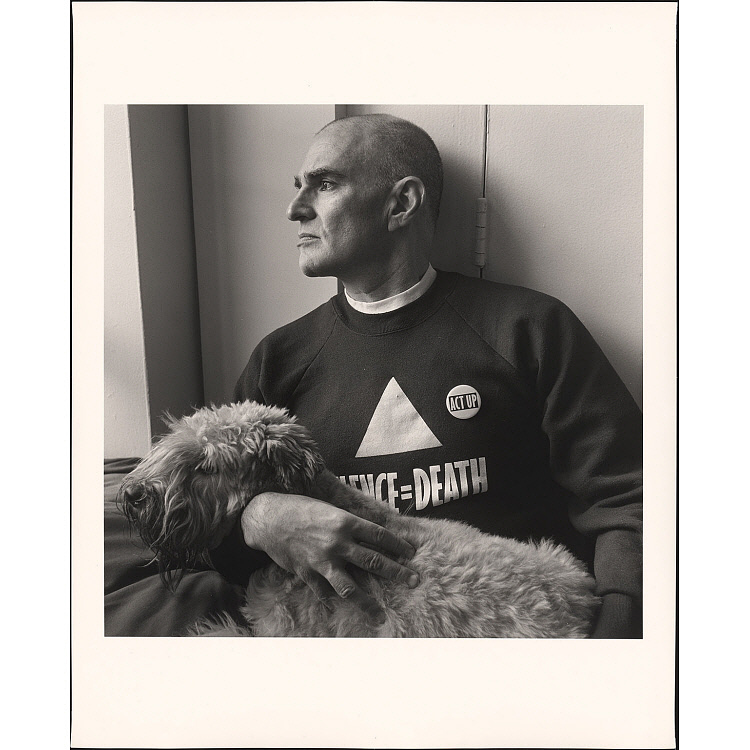

Larry Kramer with Molly by Robert Giard

Larry Kramer, pictured in this photograph with his dog Molly, was an incredibly influential playwright, author, and activist from the very start of the AIDS crisis. He organized ACT UP!, one of the nation’s first groups dedicated to AIDS research and care, and wrote “The Normal Heart”, a play that told of his personal connections to AIDS and encouraged many others to join the cause.

One person inspired by the play was Robert Giard, the photographer behind this portrait. Giard attended a performance of “The Normal Heart” and found it so moving that he began taking photographs of gay and lesbian writers. He eventually published these portraits in a book, including one of the man who’d first inspired him to do so.

While Kramer is comfortably sitting with his dog in this photo, his sweatshirt and button with the ACT UP! slogan and logo show that the home is not always an escape from the dangers of the outside world. Despite being a place of rest, Kramer’s home is also a site of planning for his activist organization and a reminder that apathy and homophobia exist outside of it.

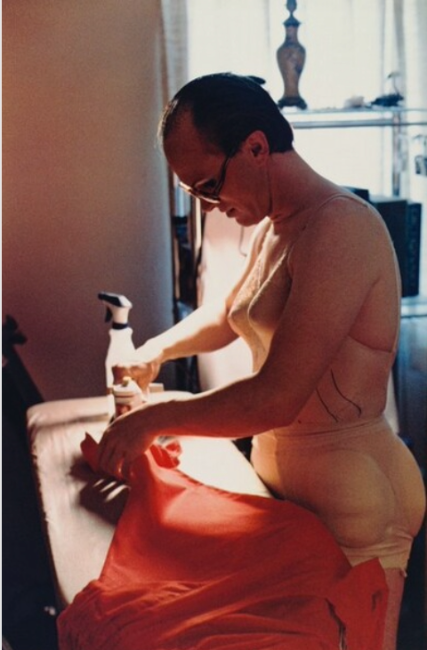

Andy Becoming Andi & Felicity, Then and Now by Mariette Pathy Allen

Mariette Pathy Allen, the photographer of both pictures, is not a queer woman, though she has spent most of her life uplifting the voices of queer individuals, especially those with diverse gender identities, through portrait photography. Allen was first exposed to the queer community when she coincidentally stayed at a hotel that was hosting a crossdressing convention, where cisgender men would dress as women. Upon befriending a group of the convention-goers, Allen made a plan to photograph them and others like them in the hopes of normalizing experimentation with gender.

"I saw, and still see, my work as art focusing on the 'de-freakification' of gender variant people," Allen says. "I saw the need to photograph cross-dressers in the daylight of everyday life, and when possible, with their wives and children, at home, or outside, and at transgender conventions."

Allen’s normalization of these men and their interest in crossdressing also helped in normalizing queer gender identities, such as nonbinary and genderfluid people. By connecting their human stories to their uncommon appearances, Allen plays a crucial role in dampening the spectacle of queer bodies.