nau | english | rothfork | publications | Pynchon's Against the Day

Tantra in Pynchon's Against the Day

This essay was published in Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 58.3 (2017): 276-86; doi: http://doi.org/10.1080/00111619.2016.1226159

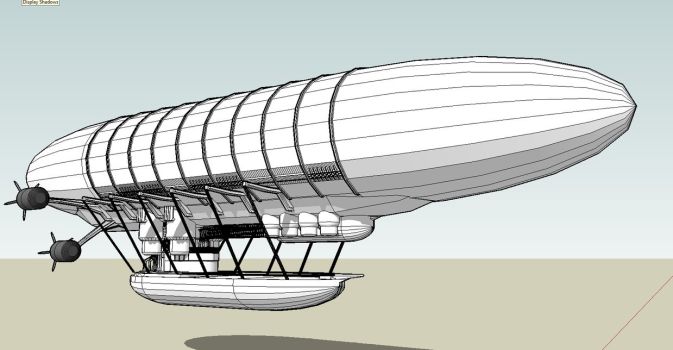

Abstract: Pynchon’s Against the Day seems to be a historical novel describing the struggle between capitalism and anarchy in the Gilded Age. However, the antagonists, Scarsdale Vibe and Webb Traverse, perish without successors. The view from the dirigible, Inconvenience, symbolizes Buddhist detachment from the battle (maya), which is elaborated by allusions to Tantra. The Trespasser, Ryder Thorn, preaches a social gospel to condemn the Chums of Chance for their dreamy detachment (p. 551). But the end of the novel endorses the Chums and the Tantric promise of the Inconvenience that floats above a violent world.

Most readers are likely to find a first reading of Thomas

Pynchon’s Against the Day to be

overwhelming. Reading the vast novel is akin to embarking on an excursion in the

airship or dirigible Inconvenience

that floats lazily over a Wizard of Oz

landscape in the novel. We have the feeling of gazing down at the pastel and

pastoral fields that go “rolling all the way to every horizon, the inner

American Sea, where the chickens schooled like herring, and the hogs and heifers

foraged and browsed like groupers and codfish, and the sharks tended to operate

out of Chicago or Kansas City — the farm-houses and towns rising up along the

journey like islands, with girls in every one … out in the yard in Ottumwa

beating a rug, waiting in the mosquito-thick evenings of downstate Illinois,

waiting by the fencepost where the bluebirds were nesting for a footloose

brother to come back home after all, looking out a window in Albert Lea as the

trains went choiring by” (71). But there are nightmares in this bucolic tableau,

even if the “balloonists chose to fly on, free now of the political delusions

that reigned more than ever on the ground” (19). On a second reading of the

sprawling novel a plot line emerges involving a world-wide war between “the

Plutonic powers” (176) of capitalism and proletariat labor dedicated to dreams

of paradise and freedom promised by anarchy. Alan Trachtenberg describes the

historic period of the Gilded Age as characterized by “struggles between labor

and capital [that] raged on the ground of culture” over “the meaning of the

nation itself” (78). In the foreword to Robert H. Wiebe’s

In The Search for Order 1877–1920,

David Herbert Donald explains “that these years witnessed a fundamental shift in

American values, from those of the small town in the 1880’s to those of a new,

bureaucratic-minded middle class by 1920” (vii).

From the view of late nineteenth century American farms and small towns, it

seemed that the railroad and the big cities, the millionaires and politicians,

“had usurped the government and were now wielding it for their private benefit”

(Wiebe 6) against the interests of Jeffersonian farmers and the churchgoing,

virtuous citizens of small towns. As Pynchon’s novel illustrates, “the rhetoric

of antithetical absolutes” between these two views “denied even the desirability

of any interchange,” much less compromise or conciliation; “the issue was

civilization versus anarchy” (Wiebe 96).

In history as well as in the novel, the antagonistic voices

seem to merge in a chorus of bewildered wailing in WWI with many “juvenile

heroes … hurling themselves into those depths by tens of thousands until one day

they awoke, those who were still alive, and instead of finding themselves posed

nobly against some dramatic moral geography, they were down cringing in a mud

trench swarming with rats and smelling shit and death” (1024).

Instead of leaving us with lament from the Lost

Generation, like Eliot’s The Waste Land,

Pynchon’s long novel suggests a radical change of cultural view symbolized by

the view from the dirigible described at the beginning and end of the novel. We

are likely to be surprised to find that an alternative, if not a resolution,

between the opposing views of capitalism and anarchy is hinted at from the

beginning of the novel in the lyrical landscape scenes, which become

increasingly important in the last half of the novel. We may be initially

puzzled by Pynchon’s interest in Tantra as a form of aesthetics to suggest how

to view or understand the lyrical passages in the novel, and surprised to find

that a kind of Western Tantra, centering on the

Inconvenience, provides an

alternative view of life to diminish desperation or religious fervor in calls

for violence to support either anarchy or rapacious capitalism.

The beginning of the novel foreshadows

WWI that “demolished

each major premise about civilized international behavior” (Wiebe 263) and saw

“the victory of elites in business, politics, and culture” (Trachtenberg 231).

The

collapse of Victorian values is illustrated by the Austrian Archduke Franz

Ferdinand who visits the 1893 Chicago World Fair (45). The royal Archduke’s

implicit claim to be devoted to supporting culture and civilization is destroyed

when he confides, “What I am really looking for in Chicago … is something new

and interesting to kill.” He suggests that in cowboy America he might be allowed

to hunt Hungarians. “The Chicago Stockyards might possibly be rented out to me

and my friends, for a weekend’s amusement?” (46). Of course, “Anarchists and

heads of state,” like Archduke Franz Ferdinand, are “natural enemies” (51),

although the aristocratic British complicate the American view since even the

agents of T.W.I.T. (True Worshippers of the Ineffable Tetractys), keen

competitors of Madam Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society (219), end up doing

journeyman work for the British Foreign Office in the Great Game of seeking to

control central Asia. Auberon Halfcourt (half in the service of the British

Foreign Office and half the disciple of T.W.I.T. in search of Shambhala)

explains that “all the meddling of the Powers has only made a convergence to the

Mahommedan that much more certain” (758) in central Asia.

Before the nightmare of WWI emerges into reality, Ryder

Thorn appears to the crew of the

Inconvenience probably in 1905. Ryder is a Trespasser or time traveler from

the future who attends “the ukulele workshop that summer” at Candlebrow

University (551). He tells the dirigible crew, “You boys spend too much time up

there” in the sky. “You lose sight of what is really going on in the world.” As

dreamy adolescents, “You think you drift above it all, immune to everything”

(553). But, he warns the Chums, saying, “You have no idea what you’re heading

into. This world you take to be ‘the’ world will die, and descend into Hell.”

And “the most perverse part of it” is that the

Victorian combatants in WWI “will all embrace death. Passionately.”

Ryder chides the young men saying this is “Not

Bosch, or Brueghel,” but the reality of “League on league of filth, corpses by

the uncounted thousands” (554).

And yet, “You children drift in a dream” gazing down

at what seems to be a tranquil landscape painting. At Chicago’s ironically named

White City, “You are such simpletons … gawking at your Wonders of Science,

expecting as your entitlement all the Blessings of Progress, it is your faith,

your pathetic balloon-boy faith” (555).

On a close reading of Ryder’s sermon, it is

important to notice how his religious rhetoric implies that the “pathetic

balloon-boy faith” in detachment, or aesthetic drifting above it all, is a moral

failure that makes the crew complicit in sending the world to Hell in WWI. The

implication suggests a different opposition from the obvious one described in

the beginning of the novel between Scarsdale and Webb or between capitalism and

anarchy. Ryder’s sermon identifies the opposition as one between Hindu and

Buddhist views of deluded and violent struggles for justice in a world of

maya (illusion), and aesthetic

detachment to avoid violence and to aesthetically appreciate perception or what

life experience offers.

The recognition of this opposition between the gospel of social justice and

Asian views that preach detachment (because they recognize that such hopes for

justice are fueled by outrage and are pursued by violence) provides a different

structure for the novel that finds a beginning, as Amy Elias recognized, in the

“mandalalike customs stamp that also may be a pilgrim badge showing Shambhala, a

central textual symbol” (Elias 41).

After Scarsdale Vibe has Webb killed by Deuce Kindred and Sloat Fresno (395),

the Traverse kids — Reef, Frank, Kit, and Lake — indolently seek to avenge their

father’s murder by dabbling in coffeehouse anarchy for a decade while roaming

most of the world. We are particularly interested in Kit’s hunting or search.

Jared Smith tells us that “Kit

travels through China and Tibet in a mock pilgrimage.”

He explains that Kit’s journey is a mockery or parody

because Kit (and perhaps the narrator) never manage to escape a Western academic

and colonial view of power versus anarchy. Smith suggests that because we are

not formed by Asian cultures, “

In her analysis, Tiina Käkelä-Puumala explains that “With

anarchists, the idea of community life without state administration and the

abolition of money come together” (156) in a dream of total freedom that ignores

how silver is extracted by blood in Colorado. Wiebe explains that in the

anarchists’ view, “Money was power; conspirators had controlled the nation by

dictating the type and quantity of legal tender [gold]; a people’s currency

[silver] would send power along with money back into the communities” (98).

Theodore Dreiser’s narrator in The Titan

explains that William Jennings Bryan promised, “There was to be ample money, far

beyond the control of central banks and the men in power over them. It was a

splendid dream” (Dreiser 400).

The

historian suggests that the political hopes of the Populists and perhaps even of

the anarchists — the “hope of Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau and Jefferson

that the private person might view his own private interests … as identical with

those of the whole society” (Trachtenberg 179) — confronted the bureaucratic

vision of Scarsdale Vibe, Frank Cowperwood, and J. P. Morgan in a head-to-head

conflict in the presidential election of 1896 between William McKinley and

William Jennings Bryan. Republican supporters of McKinley, businessmen and

manufacturers, “threatened unemployment, mortgageholders eviction, and preachers

damnation if Bryan were elected” (Wiebe 103). Although Theodore Roosevelt, “a

man almost invariably pictured in a cowboy hat” (Wiebe 132), would call himself

the Trust Buster, his Progressivism was clearly a national and international

program built on assumptions of a bureaucratic order assumed as inescapable and

self-evidently normal.

Tiina Käkelä-Puumala claims that the popularity of anarchy

as the people’s work, “clearly represent the possibility of an alternative

economy based on the ethics of mutuality” (156). Something like this

materialized in “the Bolshevik coup of November 1917” (Wiebe 275), but in

America Wiebe argues that the presidential election of 1896 marked a clear and

dramatic repudiation of socialism, radicalism, and anarchy. Instead of

recognizing the debacle of William Jennings Bryan’s campaign — Wiebe calls it a

“suicide” (102) — Pynchon ignores the election and Bryan’s defeat. Echoing popular

opinion at the time, the narrator of

Against the Day implies that Bryan was to blame for the illusory and

confused dreams about coining silver that would somehow make everyone rich, as

well as blaming him for the depression of 1893. “After 1893, after the whole

nation, one way or another, had been put through a tiresome moral exercise over

repeal of the Silver Act, ending with the Gold Standard reclaiming its ancient

tyranny, it was slow times for a while” (89-90). Instead of telling us about

William Jennings Bryan’s Cross of Gold speech or why the figurehead of the

Inconvenience features “the head of

President McKinley” (109), who was assassinated by an anarchist, the narrator

pursues a different view that will lead us in the unlikely direction of Tantra

or aesthetic detachment. The narrator describes Reef sitting in a European

sidewalk cafe watching the youthful anarchist dreamers at “the Anarchist spa of

Yz-les-Bains,” France who are “solemn young folks [who] carried with them an

austerity … a Single Idea, whose power everything else ran off of. Here it was

not silver or gold but something else. Reef could not quite see what it was”

(931). Such obsession would seem to be a radical version of Jean Jacques

Rousseau’s Romanticism declaring that the value or power of an idea is not

located in Enlightenment performance recognized as excellence, nor in

Utilitarian prosperity, but in the depth of passion experienced by the true

believer regardless of the object of belief. Buddhism identifies such emotion or

desire (tanha) as the fundamental

problem of life that is best ameliorated or controlled by detachment or by a

meditative awareness of our emotions that robs them of their compelling power.

“The Greater Discourse on Steadfast Mindfulness,” attributed to the Buddha,

declares that the monk practicing bare-awareness should be “firmly

mindful of the fact that only feelings exists (not a soul, a self or I). That

mindfulness is just for gaining insight (vipassanà)”

into our human condition to detach or liberate us “from craving” or desire so

that we live “without clinging to anything in the world,” which often fosters

violence (Mahàsatipațțhāña Sutta

20).

This would seem to lead us back to Western metaphysical or

religious claims about human nature, which promise to simply turn the wheel of a

complicated argument in another violent turn. Nonetheless critics, evidently

knowing little of Hinduism or Buddhism, have taken the bait to, for example,

claim that Pynchon’s novel expresses “a Christian and often specifically

Catholic set of doctrines,” although, in the end, Kathryn Hume suggests that

Pynchon offers “spirituality in a postsecularist, undogmatic form” (164, 181).

David Cowart believes that “Pynchon invokes

gnosticism to frame his perspective on the historical problem of evil in the

world” (401). He explains that Gnosticism is “a term fraught … with energy

subversive of various kinds of orthodoxy” (395), which would seem to make it a

near neighbor of Romantic theory, if not anarchy. Cowart also relies on

postmodern epistemology by appealing to Elaine Pagels’ analysis of early Church

history to say that “the novel reaffirms the view that we can invoke no

totalizing philosophy of history [metaphysics] or culture to make sense of the

past” (399). Toon Staes also relies on postmodernism to say that Pynchon refutes

“a mechanistic imperative” or a Modern theory to “illustrate that while there is

no single genuine interpretation of history, past events are given meaning in

the present through various discursive, and therefore ideological” theories,

views, or narratives (544). Colin Hutchinson puts it succinctly: “Pynchon at the

last moment substitutes the more hopeful notion that ‘grace’ (the last word of

the novel) is available not in utopian projections of the future … but in the

boisterous, anarchical communal life-in-the-present.”

He calls this “the work’s stoical, but cautiously

optimistic, alternative conclusion” (184). Jared Smith’s essay covers many of

the same passages I examine, but his analysis is militant in its Western

academic methods and vision to conclude that “the

novel’s anti-imperialist and anarchist objective … is not only to induce

historical disorder through a revision of a former day, but also to shed light

on the institutional forces of neo-imperialism and to project opposition toward

the established order of our time.”

These critics overlook the hint of an alternative view in

the form of the search for Shambhala (Shangri-La) that is foreshadowed by the

otherwise cryptic and easily overlooked Tibetan seal or emblem at the beginning

of the novel. Amy Elias and Robert Kohn remind us that this is where the novel

begins. The seal depicts Mt. Kailasch, a manifestation of Shiva, the Hindu

destroyer of illusion (maya; such as

the illusions of fascism or anarchy), and the home of a Tantric Buddha (Demchok),

a manifestation of divine bliss. In Vedic and Puranic Hinduism, as well as in

Tantric Buddhism, divine bliss is iconographically rendered as a sexual union

between Brahma/Saraswati, Radha/Krishna, Lakshmi/Vishnu, Shiva/Parvathi, or

Samvara/Vajravarahi. Each of these couples or consorts is not comprised of two

discrete or independent beings, but is unified or melded in bliss that subsumes,

transcends, or heals individual longing (dukkha).

Sudhir Kakar explains that a Hindu invokes “a deity not on its own but as a

couple: Sitarama and not Sita and Rama, Radhakrishna and not Radha and Krishna”

(Portrait 64). In another work, Kakar explains this bliss or moksha

(release from ego anxiety) by quoting from the

Upanisads: “just as the person, who

in the embrace of his beloved has no consciousness of what is outside or inside,

so in this experience [of moksha]

nothing remains as a pointer to inside or outside” (World

16).

In any case, the Tibetan seal would seem to lead us to the

scene in the novel where Auberon Halfcourt is searching for directions to reach

Shambhala, talking to a book-dealer in Bukhara instead of to a scholar,

Rinpoche, or Tibetan meditation

master. The bookseller seems to offer only a joke he has read about travelling

to Shambhala: “‘Even if you forget everything else,’ Rinpungpa instructs the

Yogi, ‘remember one thing — when you come to a fork in the road, take it’” (766).

This is not so different from the famous

koan of Zen Buddhism that asks the monk, “what is the sound of one hand

clapping?” Of course Auberon (the king of fairies) Halfcourt doesn’t know the

Buddhist context in which the advice points to a paradox that discursive

thinking or logic cannot solve, which should cause the monk to be less willing

to place uncritical faith in conventional reason. As a secular Westerner,

Auberon worries about “how practical” such stories are “as directions to finding

a real place.” The bookseller tells him, “It helps to be a Buddhist, I’m told,”

perhaps not in regard to finding Shambhala as a

real city meeting British

expectations, but in regard to what we mean by

real. We shouldn’t miss how this

chapter ends with no logical or discursive answers, but with a meditative,

aesthetic perception and mood that the narrator invokes by telling us, “By now

the city outside was saturated in shadow, the women gliding away in loose robes

and horsehair veils, the domes and minarets silent and unassailable against

unwished-for depths of blue, the markets wind-ruled and deserted” (767). As

though to explain the meaning of scenes like this in the novel, Sudhir Kakar

informs us that “Intellectual thought, naturalistic science” and logic that hope

“to grasp the empirical nature of our world thus have a relatively lower status

in the [Hindu] culture as compared to meditative practices or even art, since

aesthetic and spiritual experiences are supposed to be closely related. In the

culture’s belief system, the aesthetic power of music and verse, of a well-told

tale and a well-enacted play make them more, rather than less, real than life” (Portrait

182).

In another sense the search for Shambhala connects with the

Chums of Chance and Bindlestiffs of the Blue boyhood adventure stories and with

James Hilton’s novel, Lost Horizon

(1933), made into a popular movie by Frank Capra (1937).

Captain Q. Zane Toadflax, who commands “His

Majesty’s Subdesertine Frigate Saksaul” (425) in the Gobi desert, says “that the

true Shambhala will be found, just as real as anything.” When the Chums demur,

saying they “are to be counted among the basest of the base” and unworthy to

“find the holy City,” Toadflax admits he “Would’ve preferred someone a little

more karmically advanced.” What he means — or implies to readers — is someone more

spiritually disciplined. Buddhism is all about emotional discipline and control.

Its central focus is on meditation or monitoring our emotional states and

emotional reactions to perceptions and ideas to provide a kind of distanced view

of our experience that is somewhat comparable to the view offered from the deck

of the Inconvenience in gazing down

at the passing world. Among the several types or schools of Buddhism, Theravada

practice, influenced by the model of the Buddha’s life, relies most on what it

calls bare-awareness or mindfulness (vipassana)

that focuses on maintaining an awareness of our perceptions and emotions. The

most immediate effect of such practice is emotional detachment or equanimity. On

a second reading of Against the Day,

readers are likely to savor lyrical and nostalgic landscape passages of the

text, such as the long passage about Merle and Dally Rideout’s ramble through a

Thornton Wilder countryside: “they pushed out into morning fields that went

rolling all the way to every horizon, the Inner American Sea, where the chickens

schooled like herring” (71). This scene, and many like it, ramble on for long

paragraphs to provide readers with perceptions; with sights, sounds, and

memories that are not offered as gears in a discursive, clockwork argument. They

create moods and invite daydreams rather than build theories or explanations. In

the context of Buddhism, this offers a form of meditation or bare-awareness that

should suggest that our egotistic and deluded desire for the temporal and

sensual experience of life to be substituted for and explained by the

intellectual and moral abstractions of anarchy, capitalism, bureaucracy, or

Social Darwinism are illusory. These theories and beliefs express our deluded

and anxious needs for power rather than being Platonic forms or hidden forces

discoverable by science. Such theories and explanations obscure and forestall an

experience of the aesthetic or enlightened view that the landscape passages

invite us to entertain as “beyond question, with grace” (70). What Pynchon calls

grace seems to be related to what Hindus call

rasa that invites us to

taste or savor experience rather than

substituting talk, ideas, and explanations for the experience.

Sudhir

Kakar explains that “Rasa, in art”

quiets “the turmoil of chitta” or

mental processes, such as analysis, to bring the mind “nearer to its perfect

state of pure calm” (World 31).

Zen Buddhism developed

vipassana practice into the ritual of

zazen or sitting meditation as a

major practice in a highly regimented and austere monastic life. Captain

Toadflax identifies the difficulty of Buddhist practice or living in Shambhala

by saying, “if anyone ever did actually discover a City sacred as that, he might

not wish to wallow all that much among the secular pleasures, appealing though

they be” to the unenlightened. Emotional detachment through bare-awareness

requires a steely focus on our immediate perceptions in contrast to letting our

emotions carry us away where they will in the Romantic belief that such

inspiration or whimsy is divine or related to the divine. Such discipline

typically means, no drugs, no liquor, no sex, no rage, no violence, no blather

on Facebook — a price that few American readers of

Against the Day are ready to pay as

an alternative to Rev. Gatlin’s invitation to a holy war. The narrator reports

that this point “either escaped the attention of the Chums or they had heard it

just fine, and artfully concealed that recognition” (435). The narrator is

almost too artful in describing the price of such a disciplined and unemotional

life in speculating that “Such to the [emotionally] dead might appear the world

of the living — charged with information, with meaning, yet somehow always just,

terribly, beyond that fateful limen where any lamp of comprehension might beam

forth” (436). The lamp metaphor conjures the scene or tale of the Buddha’s dying

guidance offered to his disciples as translated by Paul Carus in his influential

Gospel of Buddha (1894): “O Ananda,

be ye lamps unto yourselves. Rely on yourselves …. Look not for assistance to

any one besides yourselves” (234). The context for this self-reliance is not

Romantic indulgence in emotion, nor is it a call to anarchy. The context is

bare-awareness or meditation in constantly monitoring our own emotions and

perceptions. But for Westerners, it is, no doubt, more fun to think of Shambhala

or the Pure Land as an exotic and adventurous tourist destination.

Zen Buddhism developed

vipassana practice into the ritual of

zazen or sitting meditation as a

major practice in a highly regimented and austere monastic life. Captain

Toadflax identifies the difficulty of Buddhist practice or living in Shambhala

by saying, “if anyone ever did actually discover a City sacred as that, he might

not wish to wallow all that much among the secular pleasures, appealing though

they be” to the unenlightened. Emotional detachment through bare-awareness

requires a steely focus on our immediate perceptions in contrast to letting our

emotions carry us away where they will in the Romantic belief that such

inspiration or whimsy is divine or related to the divine. Such discipline

typically means, no drugs, no liquor, no sex, no rage, no violence, no blather

on Facebook — a price that few American readers of

Against the Day are ready to pay as

an alternative to Rev. Gatlin’s invitation to a holy war. The narrator reports

that this point “either escaped the attention of the Chums or they had heard it

just fine, and artfully concealed that recognition” (435). The narrator is

almost too artful in describing the price of such a disciplined and unemotional

life in speculating that “Such to the [emotionally] dead might appear the world

of the living — charged with information, with meaning, yet somehow always just,

terribly, beyond that fateful limen where any lamp of comprehension might beam

forth” (436). The lamp metaphor conjures the scene or tale of the Buddha’s dying

guidance offered to his disciples as translated by Paul Carus in his influential

Gospel of Buddha (1894): “O Ananda,

be ye lamps unto yourselves. Rely on yourselves …. Look not for assistance to

any one besides yourselves” (234). The context for this self-reliance is not

Romantic indulgence in emotion, nor is it a call to anarchy. The context is

bare-awareness or meditation in constantly monitoring our own emotions and

perceptions. But for Westerners, it is, no doubt, more fun to think of Shambhala

or the Pure Land as an exotic and adventurous tourist destination.

The Vajrayana Buddhism of Tibet also relies on meditation,

but this Tantric method rides the back of a tiger in regard to indulging in

“spells, incantations, sacrifices, spirit possessions” (Allen 87), and other

enticements to the senses, especially sex and dreams, that hope to lead the

faithful practitioner to the recognition that all of our perceptions are

maya or fleeting illusion hardly

different from dreams. This meshes well with the magical realism of

Against the Day that proliferates

nearly endless and intricate modern or Western mandalas and rituals of science

and math, as well as a sprawling historic world tourism that fails to find

Shambhala. Kathryn Hume finds Pynchon’s rituals to be associated with “a

Catholic perspective [that] makes sense as a step in restoring the magic

destroyed by the Enlightenment project” (182). But Catholicism is not the only

religion to focus on ritual and magic. In the context of the novel, orthodox

Catholicism, much less the Bogomil heresy “going back … to the Thracian demigod

Orpheus” (956) that Cyprian Latewood embraces, is a less plausible, but probably

more familiar, explanation to American academic readers than Tantra or the

Vajrayana Buddhism of Tibet, which also relies on ritual and magic.

Jarvis reminds us that “The

Buddhist aspect of the cult [Bogomil] is particularly strong." Like

Kathryn Hume, David Cowart also makes too much of Cyprian Latewood becoming a

nun in the deviant order of the Brides of Night (961; Cowart 401). If we seek

to understand Cyprian’s religious conversion or awakening, we might better

choose to examine the seemingly inconsequential scene when Cyprian is sitting

“at a café off Kattunska Ulica near the marketplace” in Cetinje, Montenegro.

With typical irony, the narrator describes Cyprian’s response to watching a

“cooing couple” simpering over each other while also jealously having in mind

Bevis Moistleigh, a “lovestruck young imbecile [who] had actually made his way,

in that season of acute European-war hysteria, across an inhospitable terrain …

driven by something he thought was love” (847). The narrator reports that “At

great personal effort keeping his expression free of annoyance,” Cyprian “was

visited by a Cosmic revelation … namely that Love, which people like Bevis and

Jacintha no doubt imagined as a single Force at large in the world, was in fact

more like the 330,000 or however many different forms of Brahma worshipped by

the Hindu — the summation, at any given moment, of all the varied subgods of love

that mortal millions of lovers, in limitless dance, happened to be devoting

themselves to” (848). The recognition here is that

Shakti is perceived as a subjective

experience rather than recognized as an objective force like electricity.

This Vedanta recognition of how

Brahman creates and sustains the

dance of life among all individual beings in the universe through

Shakti or cosmic energy seems to have

a Theravada Buddhist effect on Cyprian who is surprised to experience something

of bare-awareness in regard to being conscious of his emotions. “He felt a

strange sober joy at the ability … to observe himself being annoyed.” Cyprian

then reflects that “There had been a time, and not too long ago, when this sort

of thing,” — his jealousy, if not disgust at Jacintha being “carelessly radiant”

in love when the world was descending into the horrors of WWI — “would have

promised a good week of queasiness and resentment. Instead he felt … a brisk

vernal equipoise, as if he were aloft” (848) or detached from his own emotions

and moral judgments; something like a view from the blimp and vaguely suggestive

of Gautama Buddha’s enlightenment based on an examination of how desire works.

There are any number of vectors or views offered in the

novel, but it seems obvious that none of the characters is willing to forego,

renounce, or even try to control desire expressed in sex, drugs, and rage, and

that their repeated indulgence causes them to experience what Buddhism professes

as its first principle, dukkha

(disappointment, ennui). Thus, they “went back once again to seeking only

orgasm, hallucination, stupor, sleep, to fetch them through the night and

prepare them against the day” (805). This may make Cyprian’s choice of Bogomil

Manicheanism (956) seem to be a kind of despair rather than liberation or

enlightenment. Reef tells us, “Cyprian must have known by now what happened to

convents in wartime. Especially out here, where it’d been nothing but massacre

and reprisal for centuries” (959).

There is much more of a dénouement in

Against the Day than in

Gravity’s Rainbow. We look for

explanations, if not resolutions, in the lives of Webb’s children who inherit an

obligation to revenge Webb’s murder and perhaps succeed him as the Kieselguhr

Kid in the fight for anarchism (“‘Kieselguhr’ being a kind of fine clay, used to

soak up nitroglycerine and stabilize it into dynamite,” 171). Adam Kirsh calls

Frank “a gunslinger who joins the Mexican Revolution” and manages to kill Sloat

Fresno. Lake — Webb’s daughter — “perversely marries her father’s murderer” who

seems to be finally caught by the Los Angeles police as a serial killer (1055).

Foley Walker kills Scarsdale before Frank can do so proclaiming, not

Allahu Akbar, but a version of the

same thing, “Jesus is Lord” (1006). Kirsh says Reef “ends up in decadent,

spy-riddled Eastern Europe” and Kit becomes absorbed in the “dippy mysticism” of

“advanced mathematics” (395).

But this is not what we find in the last chapter of

the very long novel. What we find there is a surprisingly conventional

domesticity in the last chapter. We learn that Kit and Dally “were married in

1915, and went to live in Torino, where Kit got a job” (1067). Torino proves to

be little different from Telluride. “The strike in Torino was crushed without

mercy, strikers were killed, wounded, sent into the army” (1071). We learn that

“Reef, Yashmeen, and Ljubica [Serbian for

love] returned to the U.S.” (1074) where they “run into … Frank, Stray, and

Jesse, who had the same thing in mind” — of finding “some deep penultimate town

the capitalist/Christer gridwork hadn’t got to quite yet” (1075).

“For a while they were up in the redwoods, and then

for a little longer in a town on the Kitsap Peninsula” near Seattle. There “The

girls [Stray and Yashmeen] spent hours with the baby [Plebecula], sometimes just

gazing at her. Their other gazing was reserved for Jesse, who abruptly found

himself with a couple of kid sisters” (1076).

We

find Kit in Europe “getting on and off trains bound for destinations he was less

and less sure of.” If not in an orthodox meditative state, “He would come to for

brief intervals, and then go back inside a regime of starvation and

hallucinating and mental absence” (1080).

In this state of mind, he examines “Shambhala

postage stamps … with generic scenes from the Shambhalan countryside, flora and

fauna, mountains, waterfalls, gorges [hardly different from Colorado] providing

entry to what the Buddhists called the hidden lands.” When Kit protests, saying

he thought he “was in Lwow,” Poland, Lord Overlunch corrects him: “Excuse me,

but you were in Shambhala” (1081). Lord Overlunch invites Kit to a Paris street

party with Dally inspiring another dream related by the narrator who asks us for

our consent and complicity in entertaining the dream: “May we imagine for them a

vector … carrying them safely into this postwar Paris” with “dancers who will

always be there” and with “difficulties they find are no more productive of evil

than the opening and closing of too many doors” (1082-3)?

We

find Kit in Europe “getting on and off trains bound for destinations he was less

and less sure of.” If not in an orthodox meditative state, “He would come to for

brief intervals, and then go back inside a regime of starvation and

hallucinating and mental absence” (1080).

In this state of mind, he examines “Shambhala

postage stamps … with generic scenes from the Shambhalan countryside, flora and

fauna, mountains, waterfalls, gorges [hardly different from Colorado] providing

entry to what the Buddhists called the hidden lands.” When Kit protests, saying

he thought he “was in Lwow,” Poland, Lord Overlunch corrects him: “Excuse me,

but you were in Shambhala” (1081). Lord Overlunch invites Kit to a Paris street

party with Dally inspiring another dream related by the narrator who asks us for

our consent and complicity in entertaining the dream: “May we imagine for them a

vector … carrying them safely into this postwar Paris” with “dancers who will

always be there” and with “difficulties they find are no more productive of evil

than the opening and closing of too many doors” (1082-3)?

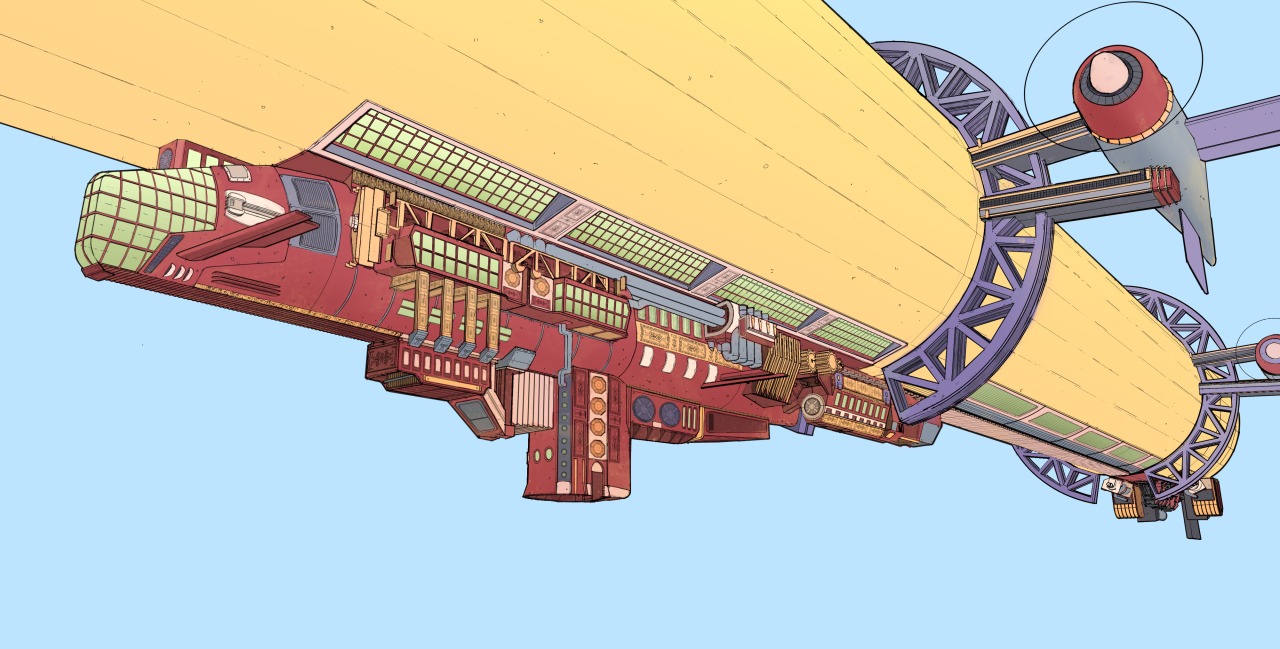

This dream is viewed from above by the Chums gazing down

from the Inconvenience. We discover

that the Chums also relish domesticity having married girls resembling

dakinis or Tantric Buddhist dancing

sky angels. The Inconvenience “had

blundered into this flying formation of girls, dressed like religious novices”

with “their metallic wings earnestly rhythmic.” We are prompted to recognize

them as Tantric angels in being cautioned against our Christian assumptions:

“Not that these wings … could ever have been mistaken for angels’ wings. The

serious girls, each harnessed in black kidskin” offered glances and “coquetries,

indistinct foreknowledge that it was to be among themselves, these somber young

women, that the Chums were destined after all to seek wives, to marry and have

children and become grandparents” (1032).

Even Pugnax, the dog, finds a mate in Ksenija (the

Compassionate). Ksenija’s “task at this juncture was to steer everyone to safety

without appearing to” (969).

This

may remind us of the popular Japanese Buddhist

bodhisattva,

Jizo, who is

believed to protect and guide, among others, the spirits of aborted fetuses to

new incarnations. Michael Jarvis suggests that Cyprian plays something of a

bodhisattva role in aiding others. A

few pages later our omniscient narrator importantly explains that “persisting

behind the world’s every material utterance, the Compassionate now took steps to

re-establish contact with Yashmeen. As if the Balkan assignment had never been

about secret Austrian minefields at all, but about Cyprian becoming a bride of

Night, and Ljubica being born during the rose harvest” (973). The Buddha is

often called the Compassionate One especially in the manifestation of

Avalokiteshvara (Sanskrit),

Kannon (Japan),

Kuan-yin (China), or

Chenrezig (Tibet). Sudhir Kakar

reminds us that “Many Buddhist images of Avalokiteswara (‘the Lord who listens

to the cries of the world’) are of a slender boyish figure in the traditional

feminine posture — weight resting on the left hip, right knee forward; they are

the Indian precursor of the sexually ambiguous Chinese goddess Kuan Yin” (Portrait

202).

It is not the Compassionate rendered as an icon or as a

Tantric power, such as Shakti

conceived of as similar to electricity (“the élan vital itself,” 714), that

Pynchon offers as a solution or alternative to the violence and chaos that the

novel illustrates, but compassion subjectively evident in the love and

domesticity of the Traverse brothers and their families, as well as in the

developing families of the Chums of Chance. This is essentially the Renaissance

claim against medieval religious belief (monasticism and celibacy) that

destroyed the art and culture of the classical world in anticipation of the

Apocalypse and dreams of a divine life beyond imagining. It is also a Hindu or

Buddhist answer that focuses on our life-long emotional needs and development

rather than on theological beliefs, academic theory, or explanations that fail

to touch our emotions (dukka). The

final image in the novel is of

Inconvenience as a city, the successor to the sham city of the dead where

the novel began. We discover that the “Inconvenience,

once a vehicle of sky-pilgrimage, has transformed into its own destination”

flying toward grace (1085). The novel offers three cities as models for life:

the sepulcher White City of colonialism, the mythic Shambhala, and the

Inconvenience grown “as large as a

small city” (1084).

Trachtenberg explains the icon of White City, “not

as an actual place, a real city, but as a frank illusion, a picture of what a

city, a real society, might look like”; a prototype for dreaming of Disneyland

or the Vatican. As he walks through the pavilions of White City, Lindsay

Noseworth, from the Inconvenience,

ruminates, “adrift between fascination and disbelief,” on how “This doesn’t seem

“quite … authentic, somehow” (23).

Trachtenberg tells us that “White City represents

itself as a representation, an

admitted sham. Yet that sham, it insisted, held a truer vision of the real than

did the troubled world sprawling beyond its gates” (231). Our narrator says it

was “at once dream-like and real” (36). Trachtenberg says it was “the momentary

realization of a dream” (230). The dream “seemed to have settled the question of

the true and real meaning of America. It seemed the victory of elites in

business, politics, and culture over dissident but divided voices of labor,

farmers, immigrants, blacks and women” (Trachtenberg 231).

True meaning or not, we dream.

And our novel suggests that loony dreams of a

ukulele conference at Candlebrow University or of sexy angels in black lambskin

(dakinis) are better than dreams of

justice that entail the nightmares of WWI.

Trachtenberg suggests that the map or guide for White City

might have been drawn by Edward Bellamy’s popular notion of utopia provided in

Looking Backwards (1888).

The narrator-guide in the novel explains that in

this future world, “everybody is part of a system with a distinct place and

function.” This might presage fascism and the immense military rituals of Nazi

Germany or Mao’s China, but for that fact that “Happiness in

Looking Backward,” as in White City,

“is identified entirely with leisure and consumption — the consumption of

religious emotions of ‘solidarity’ as much as of the cornucopia of goods

produced by” capitalism (Trachtenberg 50).

Instead of an alabaster prototype for clean shopping

malls produced by American engineering, Shambhala is the dream of Tantric

Buddhist shamans. Yashmeen writes to her father, Auberon Halfcourt, to claim

that either Shambhala is “as close to the Heavenly City as Earth has known, or”

it will become “Baku and Johannesburg all over again, [with] reserves of gold,

oil, Plutonian wealth, and the prospect of creating yet another subhuman class

of workers to extract it. One vision, if you like, spiritual, and the other,

capitalist. Incommensurable, of course” (631). The closest anyone comes to

Shambhala seems to be Kit who at one time “entered a strangely tranquil part of

Siberia, on the Mongolian border … which Prance had been briefly through and

said was known as Tuva” (786). After listening to Tuva throat singing that seems

to produce two sounds at once, Prance says, “Perhaps shamans are not the only

ones who know how to be in two states at once” (786). This should remind us of

bare-awareness that observes how we simultaneously experience emotion and can

also monitor or be aware of the emotion. Again, readers are likely not to notice

the detached and aesthetic perception of Kit who seems to find Shambhala at the

very moment when Prance says, “Shambhala may have vanished in that instant” of

the Tunguska event or the 1908 meteor strike in Siberia “from their list of

priorities” or from the concerns of T.W.I.T.

Instead of reassessing to focus on a new priority in

the endless quest for power or to conjecture about causes of the event or what

it might mean, “Kit rode away over a patch of open steppe” to listen to “bass

throat-singing again. A sheepherder was standing angled, Kit could tell,

precisely to the wind, and the wind was blowing across his moving lips, and

after a while it would have been impossible to say which, the man or the wind,

was doing the singing” (787). The two become one with the perception offering

beauty but no discursive message or meaning. The answer to the complexities

offered by the novel, if we can call it an answer, seems to be

rasa, beauty, or grace.

A few pages later, Kit runs into Fleetwood Vibe, the son of

Scarsdale, who is, he says, looking for “a hidden railroad” (789) that might

take him to Shambhala. Fleetwood asks Kit, “Do you remember once, years ago, we

talked of cities, unmapped, sacramental place …”?

Kit cuts him short, saying, “Shambhala ….

I may have just been there.” After failing to

explain to Fleetwood how he had been

in Shambhala, through aesthetic reverie, Kit tells him, “you’re like every other

so-called explorer out here, a remittance man with too much sense of privilege,

no idea what to do with it” (790). What he means is that Fleetwood can only see

what his capitalist and bureaucratic culture has enabled him to see in

processing his perceptions to make sense of them. The price of entering

Shambhala is the erasure or abandonment of the capitalist, bureaucratic, and

ritual view as well as the expectation of academic answers or technical control;

to exchange these for an aesthetic, silent, and bare-awareness perception or

experience. Rather than explain this, the narrator says, “The two of them might

have been sitting right at the heart of the Pure Land, with neither able to see

it, sentenced to blind passage” through life; “Kit for too little desire,

Fleetwood for too much” (791).

A few pages later, Kit runs into Fleetwood Vibe, the son of

Scarsdale, who is, he says, looking for “a hidden railroad” (789) that might

take him to Shambhala. Fleetwood asks Kit, “Do you remember once, years ago, we

talked of cities, unmapped, sacramental place …”?

Kit cuts him short, saying, “Shambhala ….

I may have just been there.” After failing to

explain to Fleetwood how he had been

in Shambhala, through aesthetic reverie, Kit tells him, “you’re like every other

so-called explorer out here, a remittance man with too much sense of privilege,

no idea what to do with it” (790). What he means is that Fleetwood can only see

what his capitalist and bureaucratic culture has enabled him to see in

processing his perceptions to make sense of them. The price of entering

Shambhala is the erasure or abandonment of the capitalist, bureaucratic, and

ritual view as well as the expectation of academic answers or technical control;

to exchange these for an aesthetic, silent, and bare-awareness perception or

experience. Rather than explain this, the narrator says, “The two of them might

have been sitting right at the heart of the Pure Land, with neither able to see

it, sentenced to blind passage” through life; “Kit for too little desire,

Fleetwood for too much” (791).

The capitalism of Scarsdale Vibe is dedicated to producing the sterile police state of White City. The Chicago and Los Angeles of the novel are caught midway between a police state and anarchy almost as Norman Mailer suggested in Of a Fire on the Moon with the future of the nation pulled between the antipodes of NASA in Houston and sprawling, crime-ridden Los Angeles. Shambhala remains, like the moon, alluring and exotic. The narrator, concerned about the Inconvenience, explains that the Tunguska event seems to have “torn the veil separating their own space from that of the everyday world” so that they “met the same fate as Shambhala.” That fate is to “allow human eyes to see the City” that had “For centuries … lain invisible” (793). The Inconvenience does not visit a physical Shambhala, like it does White City and Los Angeles, but, “Returning from the taiga, the crew of Inconvenience found the Earth they thought they knew changed now in unpredictable ways” (795). Not in Shambhala, “they were on the Counter-Earth, on it and of it, yet at the same time also on the Earth they never, it seemed, left.” This dual consciousness is not produced through vipassana, disciplined meditation, or shamanistic dreaming. Rather it “had to do with the terms of the long unspoken contract between the boys and their fate — as if, long ago, having learned to fly, in soaring free from enfoldment by the indicative world below, they had paid with a waiver of allegiance to it and all that would occur down on the Surface” (1023). This would seem to be something close to bare-awareness in fostering emotional detachment. Shambhala is not exactly lost or replaced by “the City of Our Lady, Queen of the Angels” (1032), but we cannot entirely live everyday lives in Shambhala any more than we can in the moment of proclaiming Romantic freedom or in anarchical dreams and longing for utopia. Most Americans, despite an interest, are not invested in or shaped by Vajrayana or Theravada Buddhism, which for us may remain as exotic as Shangri-La. If not the White City, our monastery for the practice of something like bare-awareness or aesthetic reverie that grants entry into Shambhala is more likely found in the “Inconvenience, once a vehicle of sky-pilgrimage … transformed into its own destination”; a community where the focus is on technology to support health, prosperity, love, families, community, and above all, beauty. This is not the Social Darwinian capitalism of Scarsdale Vibe but neither is it anarchy. The mantras and rituals of electricity — “It could have been a religion, for all he knew” (98) — along with all the math and physics lore, as well as the non-academic allusions to Tantra — constitute the possibility of a new American monastery or method that does not promise to replace the actual Chicago or Los Angeles, but it can promise to supplement politics and consumerism with an aesthetic dimension, which some cultures — Hinduism and Buddhism — see as divine or expressive of the divine. Perhaps the illustration of meditative and aesthetic detachment is evident, not in exotic Hindu or Buddhist icons, but in Stray and Yashmeen who “spent hours with the baby [Plebecula], sometimes just gazing at her. Their other gazing was reserved for Jesse, who abruptly found himself with a couple of kid sisters” (1076). This is why, or how, the Inconvenience floats above the ground like a cloud, not as a literal model of Shambhala, nor as a vehicle to reach Shambhala, but as a developing community that Renaissance science, engineering, art, and even capitalist bureaucracy, aspire to develop. If technology creates the machineguns of WWI and even the atomic bombs of Gravity’s Rainbow, it also constructs the Inconvenience from whose platform, above the “black grease-smoke, the effluvia of butchery unremitting” (100), we gaze on beauty and “fly towards grace.”

Works Cited

·

Allen, Charles. The

Search for Shangri-La. London: Little, Brown & Company, 1999.

·

Bellamy, Edward.

Looking Backward. 1888. New York: Dover, 1996.

·

Carus, Paul. The

Gospel of Buddha. 1894. Chicago: Open Court, 1917.

https://archive.org/details/gospelofbuddha008430mbp

·

Cowart, David. “Pynchon, Genealogy, History:

Against the Day.”

Modern Philology, 109.3 (Feb., 2012):

385-407.

·

Dreiser, Theodore.

The Titan. New York: John Lane, 1914.

·

Elias, Amy J. “Plots, Pilgrimage, and the Politics of Genre

in Against the Day.”

Pynchon’s

Against the Day: A Corrupted Pilgrim’s

Guide. Eds. Jeffrey Severs and Christopher Leise.

Newark: University of

Delaware Press, 2011:

28-46.

·

Hume, Kathryn. “The Religious and Political Vision of

Pynchon’s Against the Day.”

Philological

Quarterly (2008): 163-87.

·

Hutchinson, Colin. “The Complicity of Consumption: Hedonism

and Politics in Thomas Pynchon’s Against

the Day and John Dos Passos’s USA.

Journal of American Studies, 48.1

(2014): 173-98.

·

Jarvis, Michael. “Very Nice Indeed: Cyprian Latewood’s

Masochistic Sublime, and the Religious Pluralism of

Against the Day.”

Orbit, 1.2 (Apr. 10, 2013).

https://www.pynchon.net/articles/10.7766/orbit.v1.2.45/

·

Kakar, Sudhir.

The Indians: Portrait

of a People.

New York: Penguin, 2009.

·

________. The Inner

World: A Psycho-Analytic Study of Childhood and Society in India, 2nd

ed.

Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1981.

·

Käkelä-Puumala, Tiina. “‘There is Money Everywhere’:

Representation, Authority, and the Money Form in Thomas Pynchon’s

Against the Day.”

Critique, 54.2 (2013): 147-60.

· Kirsh, Adam. “Pynchon: He Who Lives by the List, Dies by it.” New York Sun, Nov. 15, 2006. http://www.nysun.com/arts/pynchon-he-who-lives-by-the-list-dies-by-it/43545/

· Kohn, Robert. “Pynchon Takes the Fork in the Road,” Connotations, 18.1-3 (2008-09): 151-82. http://www.connotations.de/pdf/articles/kohn01813.pdf

·

Mahàsatipațțhāña Sutta:

The Greater Discourse on Steadfast

Mindfulness. Trans. U

Jotika and U Dhamminda.

Migadavun Monastery, Ye Chan Oh Village, Maymyo, Burma, 1986.

http://www.buddhanet.net/pdf_file/mahasati.pdf

·

Pynchon, Thomas.

Against the Day. New York: Penguin, 2006.

·

Smith, Jared. “All Maps Were Useless—Resisting

Genre and Recovering Spirituality in Pynchon’s

Against the Day.”

Orbit, 2.2

(Feb. 23, 2014).

https://www.pynchon.net/articles/10.7766/orbit.v2.2.52/

·

Staes, Toon. “‘Quaternionist Talk’: Luddite Yearning and

the Colonization of Time in Thomas Pynchon’s

Against the Day.”

English Studies, 91.5 (Aug., 2010):

531-47.

·

Trachtenberg Alan.

The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age. New

York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

·

Veggian, Henry. “Thomas Pynchon

Against the Day,”

Boundary 2, 35.1 (Spring, 2008):

197-215.

·

Wiebe Robert H. The

Search for Order 1877—1920. New York: HarperCollins, 1967.

* * *

|

|