nau | english | rothfork | publications | Reynolds' Agatite Trilogy

The Missing Beauty in Clay Reynolds' Agatite Trilogy

This essay was published in The Texas Review, 25.3-4 (Fall/Winter, 2004): 80-102.

Abstract:

The Agatite trilogy is a regional work concerned about the diminished quality of life for those living in the small towns of West Texas; lives that seem to have little possibility for beauty and pride of accomplishment. In Agatite Reynolds illustrates the male reaction of violence to the cultural impoverishment of the region. In The Vigil he illustrates an opposite female reaction of disengagement and minimal response. In Monuments Reynolds uses the character of Jonas to illustrate why renewal of a town like Agatite is impossible—because it lacks the cultural resources required to foster deep and accomplished professional lives. Monuments ends by suggesting (in the character of Linda) that the real legacy any community can leave is a dedication to beauty (art). The legacy of the small West Texas towns is the Agatite trilogy.

![]()

Academic readers are likely to judge Reynolds’ Agatite trilogy to be his best work (composed of the novels The Vigil [1986], Agatite [1986], and Monuments [2000]). It is Reynolds bad fortune—which is ultimately his good fortune—to be compared to the two greatest Texas writers, Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry. The Agatite trilogy is a near neighbor to McMurtry’s Thalia trilogy composed of The Last Picture Show (1966), Texasville (1987), and Duane’s Depressed (1999). Larry McMurtry took vicious glee in illustrating the cultural impoverishment of small town life in West Texas. In Texasville, he reduces literature to the tee-shirts Karla wears with such slogans as: “IF YOU LOVE SOMETHING SET IT FREE. IF IT DOESN’T RETURN IN A MONTH OR TWO HUNT IT DOWN AND KILL IT” (6). In Duane’s Depressed, Duane reads Thoreau and Proust but must drive to Oklahoma City to find anyone else who has read such works.

Reynolds says that for him the small towns of West Texas “sit like starving sentinels of a bygone age.” They were “‘Huck Finn’ kinds of places when I grew up [...]. Now much of that has changed. Or had it? That’s what I wanted to come home to, that’s what I wanted to write about” (“Profits” 55). Reynolds expresses less irony and more compassion than McMurtry in his judgment about small town Texas life even though his Agatite is more insipid than Thalia. Although “Huck Finn kinds of places” implies adolescent hope about the possibilities of life, Reynolds’ characters find scant opportunity for fulfilling lives on the Texas plain. In Agatite the hope is for an entirely different, unknown life; a hope preached every Sunday in the fundamentalist churches of the flat land. It is a hope that often enough generates an explosive violence to end the bleak waiting for something authentic, something that one could be dedicated to because it would provide meaning, beauty, and honor.

Roy Breedlove did not set out to kill anyone on a Saturday night. His violence expresses a desperate hope to force life to reveal something extraordinary, overwhelming, and unquestionable; something that might be called beauty. Naturally there is no allusion to Kierkegaard’s Abraham, but his willingness to murder his own child to reach beyond the ordinary and to hopefully discover some absolute alterity is shared by Roy in an impoverished and inarticulate way. R. S. Gwynn’s comment about the town of Agatite as it is portrayed in The Vigil also offers insight into Roy’s violence: “Anyone who has spent time in a place like Agatite, who has experienced the inexorable repetition of routine that passes for life, will know that Imogene’s vigil is one that she does not endure alone” (Gwynn). The Vigil illustrates the female pathology caused by deprivation: slow suicide, catatonia interrupted by hysteria. Agatite illustrates the male pathological reaction: the attempt to violently escape ennui and frustration. Monuments offers a more equivocal view by offering nostalgia about childhood and adolescence in the Huck Finn small towns of Texas. But recognizing that for sentiment, it ultimately suggests that it is probably best to simply continue driving through the dying hamlets without stopping to try to fathom why some people continue to abide there in such cultural, social, and aesthetic deprivation.

Roy Breedlove, the main character in Agatite, is an aimless young man with only the most tenuous social involvements. He is a tumbleweed blown by the primal winds of “breed” and “love.” His “breed” is that of the played-out frontier adventurer who is unaware that opportunity has moved on to “Amarillo or Fort Worth, Abilene, or Lawton [. . .] one of those more inviting metropolises.” Because “time and progress had stopped in Agatite,” Roy wanders in a cultural wasteland; “there was little indication that the town was aware that men had walked on the moon, that hearts were transplanted, or that war had become unpopular.” Civic discussion is reduced to speculating “on the worth of the nine- and ten-year-old boys scrimmaging on the playgrounds around the elementary school” (3). Will these children grow up to make Agatite an interesting or inviting place to live? No. “Children simply grew up and left. They talked about leaving from the time they were old enough to be aware that there was anywhere else to be” (6).

Had Roy found a job and a life in Amarillo or Fort Worth, he would have found diversions and entertainment enough not have been one of those who hunger for something more out of life than it seems willing to give. He would have become one of somnambulant—Natty Bumpo reduced to worrying about keeping a lawn and praying on Sundays for a better life. Roy’s failure is a kind of perverse success, a conservative gesture against “college kids, communists, and other riffraff the government suffered to exist in the world” (31). Generally “only money or disgrace could really convince most to return to live in Agatite forever” (6). Roy’s return, to rob a bank and shoot up the town, parodies the frontier past when grandparents of the current residents had the gumption to come to the wild and empty plains of Texas to build new and different lives. Now, because there is so little of value in Agatite, it does not matter if it is shot-up. Its destruction can be viewed as a kind of euthanasia. In any case, Roy’s violence perpetuates a crippled or senile version of the frontier myth: real men do not take “it,” and, when pushed far enough often enough, they erupt in what they feel will be a cleansing violence, a baptism of fire that at least in the moment of rage proves their manhood and pride.

The young who leave Agatite cannot articulate exactly what is wrong with life there, but they are healthy enough to flee the flat land and the empty sky, to escape cultural starvation and their anxious, defensive parents who fear that “something out there threatened them in a way they could not imagine.” Reynolds’ calls towns like Agatite “sentinels” as if the residents still hope for a Comanche raid to prove to each other that something of worth remains. Instead of an enemy they could deal with, the citizens of Agatite feel that their town is diseased or perhaps suffering the effects of old age as surely as when “the railroad had gone away and left them with no future to count on.” More than this, they feel they are under attack by the outside world that has moved beyond them. “Some power, some evil perhaps . . . something greater than their comprehension or ability to resist or control” stalks them like the image of Satan conjured in the local Church of Christ. Reynolds’ Texas peasants hunker down to sneer at anything unfamiliar, especially at lifestyles and professions they cannot imagine. Suspicious and fearful of anything they do not know—and they know almost nothing—the citizens of Agatite seek reassurance in one of “the seven Protestant churches in town” where they hope to be rewarded for their longsuffering patience (5). Jesus and the Rapture will “save them” by giving them a new, unimaginable life without the hazard and struggle of education and a profession. But Jesus does not come in the clouds and the tedium of empty, frumpish lives is relieved instead by occasional explosions of mindless, adolescent violence that may offer brief catharsis but fails to redeem or to reveal anything seductive or worthwhile.

In describing Roy Breedlove, Terence Dalrymple diagnoses the disease afflicting Agatite: “Drifting from place to place [...] Breedlove finds himself in deeper and deeper trouble not because of some [...] malicious force but because of his own uncertainty.” Faced with choices that will decide his future, Roy “consistently chooses not to choose but, rather, to allow haphazard circumstance to guide him” (Dalrymple). The small towns contain the sifted chaff of those who could not find anything worth pursuing in life, anything interesting or challenging or enticing enough to leave Agatite in order to pursue, people who ironically envy the energy and rage that Breedlove summons in his attempt to kill the geriatric weariness of Agatite.

Breedlove illustrates traits of the violent cowboy type whose character was shaped by the American West and its frontier small towns. On Sunday morning he is as puzzled as everyone else in town. Having robbed the Agatite bank and precipitated a gun battle that left two-dozen corpses, Roy reflects:

He hadn’t meant any of this to happen. It was all some kind of crazy accident. He wasn’t a killer, not really. He didn’t have the courage to be a killer. Hell, he thought [...] he didn’t even have the courage to face up to a pregnant girlfriend. He had just run away. And that’s what he would like to do right now. But there was no place to run, and he knew it. (361)

Is Breedlove a vandal or revolutionary bent on destroying decadence in hopes of liberation, in hopes of exposing some primal courage or vision of beauty that would rouse his neighbors to dedication and devotion? His life is too vacuous to offer such lofty ambitions or considered decisions. At best, the narrator offers an oblique explanation for Roy’s violence, saying, “Agatite would always feel a perverse kind of gratitude for what Roy Breedlove did, for the one brief moment of unique violence that gave the town something as hard and lasting as the stone for which it was named” (374). Even though it is, as Roy tells us, meaningless, his murder spree must seem to many like evidence of an enviable commitment to some quixotic cause or purpose. Like Abraham of old, Roy seems to have found something worth killing for.

Though Roy is no hero, he has lived a life larger than his stay-at-home steer-like neighbors who married and settled for penurious jobs at the lumber mill, hardware store, gas station, grocery store, and school district. High school sex is a kind of lure used to dupe kids into staying, “as if the town were some sort of trap, ready to spring and keep them there” (6). The novel is composed of explicitly dated vignettes, most devoted to sketching Breedlove’s life in an apparent attempt at explanation, analysis, or illustration. The opening scene is reminiscent of James Joyce’s “Araby” where a boy hopes to win a carnival prize for his love but only succeeds in discovering how shabby life is. Roy’s girlfriend, Cassie Crane, breaks up with him a few days before a senior class outing to an amusement park in Oklahoma. Roy feels that his problems with Cassie would be solved, if only he had the money to entertain her. A carnival attraction, a maze of mirrors, offers the lure of easy money. A twenty-dollar bill and the prospect of entertaining Cassie wait at the exit for Roy, if he can successfully find his way through the maze. When he manages to do so, Roy discovers that the money is sandwiched between two panes of glass so “there was no way he could get to the bill without breaking the window, and he briefly considered it” (29). Frustrated by how close the inaccessible prizes are—the money, the girl, and the promise of a better life—Roy cannot muster the moral outrage necessary to break the glass and escape the maze. He simply stands there, absorbing the lesson that he is a loser, that he cannot win, that life is a rigged carny game. Russell Long finds a different message in this scene. He believes that all the characters in the novel “are running mazes, looking for a system which will take them to their prize, and they all learn—usually through spectacular and violent failure—that the prize is only an illusion” (Long).

Roy flees from Cassie, not because he is ambitious or has other plans or is attracted to someone more beautiful, but because “he didn’t want to work in any goddamn lumberyard, and he didn’t want to marry her” (38). Roy thinks of himself as special but cannot say how or why when his father, the town drunk, lectures him about getting Cassie pregnant: “All young men . . . how do you think you came into the world?” (37). Roy is a boy who does not know how to become a man having some measure of pride and purpose. What kind of a man would consent to live in Agatite where there is nothing worth doing? Roy wants more than Cassie and Agatite can offer but without schools, culture, institutions, and the example of professionals, Roy has no positive model to illustrate what he wants. With the sneer and slouch of Billy the Kid, he considers his own child as simply another impediment: “‘It’ was always it. Never him or her, only it, a shapeless thing in his mind that would never have a name or personality [...]. But it was an it, a thing that screwed up his life” (39). Roy wanders the fugitive sections of Fort Worth, Dallas, Wichita Falls, and finally Los Angeles. His lack of education and profession make these places an indistinguishable series of bus stations, bars, and flophouses. An indigent pilgrim of the wasteland, without a fraction of the depth of Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree, Roy prowls the places where the threat to an authentic life seems to brood. Like the old-time frontier scout in Reynolds’ Franklin’s Crossing, Roy wanders around lost much of the time until violence strikes as randomly as a tornado in the West Texas spring.

A second plot in Agatite concerns a body that is discovered in an old, seldom-used privy behind the Hoolian Barbershop. Hoolian was once a town or had the hopes of becoming one as explained in The Tentmaker (2002), but it is little more than a barbershop that doubles as a geriatric center of sorts for doddering old men. The corpse of a young woman is found hanging from a rafter in the privy. Who she is and how she got there are a mystery until readers discover that Breedlove murdered Eileen Kennedy, hoping to make it appear that she hanged herself. Roy found her struggling with her stalled car. He flirted with Eileen until they recalled how they knew each other. Eileen was a bank teller who belatedly recognized Roy as the man who kept her at gunpoint in a robbery that understandably traumatized her. The struggle in which she is murdered is fraught with the kind of detail and slow motion treatment characteristic of novelistic sex scenes. Perhaps it was this scene that caused one reviewer to identify Reynolds’ technique with that of Theodore Dreiser in such famous scenes as Clyde Giffith’s watching his pregnant girl friend drown or Hurstwood finding the safe locked and the money in his hand (Carden). Ultimately, neither mystery is entirely explained. Sheriff Able Newsome can only guess at the details of the murder and puzzle over why Roy behaved as he did in the Agatite bank.

Renyolds does not suggest that some kind of determinism or even the operation of fate that masquerades as coincidence was at work to explain Roy’s tragedy. Instead, he suggests that cultural impoverishment and a perverse hope to discover beauty and honor motivate Roy’s desperate acts. When Reynolds’ male characters lose control of their dull and empty lives, they embrace violence in a desperate hope for a different, more authentic, if not better life. In The Vigil, the first novel in the Agatite trilogy, Reynolds depicts a woman whose taciturn and brittle composure suggests a kind of near relative to violence hammered foil thin by decades of tense expectation for a better life. Imogene McBride’s life is a study in minimalism. She has nothing, she does nothing (or next to nothing), and she has no one. Consequently, she fits perfectly into the wasteland of Agatite. Imogene and Cora, “her beautiful eighteen-year-old daughter” (5), were on their way to Oregon when their car broke down in Agatite. Imogene had left her philandering husband in Atlanta and was heading to Oregon to stay with her sister, Mildred. Cora is the first of Reynolds’ teenage blond Madonnas who stun men with their beauty, causing them to feel that their lives are an aching wait to serve such beauty.

Cora crosses the street to enter Pete’s Sundries and Drugs to buy a five-cent ice-cream cone and disappears, leaving her mother sitting on a bench in front of the courthouse. There are few clues about her disappearance. Life in Oregon, however, does not promise to be what life in Atlanta was where the McBrides “had two maids, a chauffeur, a cook, and a gardener.” In Atlanta, Cora wore handmade dresses, went on “expensive vacations,” and was “a debutante and a very sophisticated beauty” (8). Her mother thinks Cora may have run off in an act of teenage rebellion, complaining to herself that “she wears too much makeup for a girl her age, and she’s always wanting to fix her hair like those trashy movie stars.” Worse, “she had taken to buying all sorts of cheap perfumes and wearing bright, printed scarves and heavy imitation pearl necklaces and other junk that made her look tacky and—Imogene winced at the thought—of easy virtue.” Cora began wearing peasant blouses “low on her delicate shoulders and would have continued to wear [them] that way if Imogene had not put a stop to it.” Imogene voiced her displeasure more than once to Cora, promising, “Well, there would be none of that in Oregon” (11). Imogene’s conventional moral concern and her lack of understanding about economic and professional life suggest that she has never grown up.

Though mysterious in method, Cora’s disappearance seems fairly predictable when one considers that her mother took her out of high school when she was “so close to graduation” to keep her away from her boyfriend. Moving to Oregon “would serve the purpose of keeping her far away from Joe Don Jacobs [...]. He would only break Cora’s heart or, worse, leave her pregnant while he went off with some cheerleader” (12). Imogene could not control her husband, Harvey, who “spent his time and pleasure in the company of bleached blondes and trashy redheads” (8). Nor can she control Cora, who “had a way of walking that bothered her.” Cora’s “hips undulated as she moved from step to step, and her breasts seemed actually to rise and thrust forward.” Imogene wonders, “if Cora wore any underwear” and vows “to do something about that walk” when they reach Oregon (10). So it is hardly surprising that Cora manages to escape before reaching Oregon, a place that promises to be as poky as Agatite.

Without culture, education, and exemplars, new and more authentic lives are not easy to invent. Almost two hundred pages and a year-and-a-half later, Sheriff Ezra Holmes “discovered what happened to Cora Lee McBride” (192). “She had been working as a prostitute in the New Orleans area for more than a year,” when “for reasons known only to her and God, she put a pistol to her head and pulled the trigger” (193). Cora leaves behind a baby. “Pinned to his dirty pajamas was a piece of newspaper where someone, likely his dead mother, had simply scrawled in eyebrow pencil, ‘Joe Don McBride’” (194). One might expect Imogene to leave her bench to fix her attention on her grandson, but Sheriff Holmes does not tell her about the child, deeming Imogene to be emotionally dead or insane. Her life stalled midway between Atlanta and Oregon, her daughter vanished, Imogene controls nothing but her stunted emotions; “she was determined to wait for Cora to come back, no matter how long it took” (19). Her female patience—involving a thirty-year vigil on a courthouse bench—matches Roy’s violence; both are determined to force life to reveal something more than they know, something more than the tawdry and conventional, something transformational. R. S. Gwynn’s comment, which reminds us of Reynolds’ interest in the theater, is double-edged. He says, “Perhaps her vigil, as Holmes himself realizes, is a pattern she has imposed on a heretofore aimless life to give it some meaning, the cause of her thirty-year watch becomes so distant as to be absurd. Even in a remote Texas town the spectre of [Samuel] Beckett lingers” (Gwynn). Which is it? Does Imogene actively, even if minimally, create a faint pattern and meaning for her life? Or does she wait for Godot and deliverance?

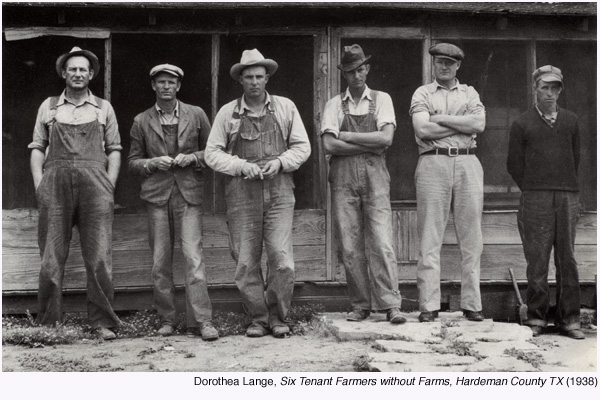

Quanah, TX 1952 |

After watching over her for a year, Holmes, a widower, makes a slow and

cautious approach for companionship. Planning to retire, he asks if she

would “give all this up and go along with me” (176). Imogene throws a

glass of ice water in his face and calls him a son-of-a-bitch, glaring

“with a cold fury Ezra had seen before and found dreadful.” Instead of

acknowledging Holmes or the reality of her situation, Imogene lashes out

in a hated meant for her former husband. She thinks of herself as an

innocent, a female victim with a blond, unsullied daughter. “You

lured me over here as a friend, a friend!” “I’m not

one of your slutty tarts! Your damned whores!” she continues. “Is that

what you think I am?” (176). When the sheriff “reached out for her hand,

trying to calm her down,” she screams, “I’m a married woman! Not

some fly-by-night trash who sells her life and her body” (176-7).

There is no pattern of a new and better life. There is only regression,

denial, and a pathetic expectation that someone else should deliver

meaning and beauty to make life better. This is Reynolds’ recurrent

theme in the three novels; the hope for a better, more aesthetic, life

and total ignorance about the educational and cultural investments

necessary to reach that life. Imogene has grown to adulthood, but in Agatite she literally sits down to withdraw into dreams of her own childish innocence. Everyone else in her family may have run away from her, or run around on her, but Imogene sits where she is, prim and innocent as a child. “Sometimes toward the beginning of her third winter on the bench, Imogene forgot why she sat out there every day. She was no longer consciously waiting for Cora to return” (203). Imogene McBride is a bride left at the altar of life, relieved because she does not have to face the honeymoon bed. She would hardly be noticed, if, like so many others, she had hidden her trauma a bit deeper to sit meekly in church waiting for the promise of a new life. It is her publicly insistent display that, like male violence, brings her plight to the attention of people in Agatite as something vaguely resembling culture. |

In the “Epilogue” the narrator reports that when she finally moved off her bench to become somewhat involved in the frail life of the town, Imogene “never watched TV, read a newspaper or magazine, or really talked to people.” With no hope for a family or a normal life, “she had not prayed since the forty-first day after Cora disappeared” (213). The suggestion is that Imogene, by remaining in the wilderness a day longer than Christ, is a day more virtuous—or so she thinks. This self-righteousness may remind some readers of Faulkner’s primitives in As I Lay Dying. In that novel, Cora Tull masks the harsh realities of life with loquacious, self-righteous fantasy. The symmetry is not between the two Coras, but between Faulkner’s Cora and Reynolds’ Imogene. Faulkner’s Cora never shuts up while Reynolds’ character rarely speaks. When she does, the resemblance is evident: both women are studies in female narcissism; both are innocents who are convinced that the world continually wrongs them. The world is largely identified with men and sexuality because the girls refuse to grow up to accept an ambiguous world beyond their Sunday school control. Lacking Roy’s male bent for violence, Cora Tull still means to set things straight. Her husband reflects that if God could turn creation over to anyone, it would have to be Cora: “And I reckon she would make a few changes, no matter how He was running it” (Faulkner 54). Imogene is even more puerile, patiently waiting for daddy to set things straight to her little-girl satisfaction.

Because Imogene is so inarticulate, Reynolds provides additional explanation in the novel’s “Afterword.” According to Reynolds, Imogene is “not sitting out there because of Cora; she’s not really waiting for her to return. But she has nothing else to hold onto” and nothing else to do. He calls Imogene lucky because she “has a town to belong to in a way that she has never belonged to anything before” (217). But Reynolds cannot give Imogene nostalgic memories of a Huck Finn childhood in Agatite. Instead he puts her on a bench to wait forever for something like that idealized childhood. Imogene is a classic narcissist. Eventually forgetting her heart’s desire (a suggestion also associated with Cora’s name), Imogene regresses to a state resembling early childhood in which she patiently waits for adult life to conform to the Sunday school patterns that were promised to her as a little girl. The nearly incredible part of the story is that no one in Agatite recognizes Imogene’s pathology for what it is.

Imogene is a counterpart to Roy Breedlove. Both fail at love and lose their children. Neither has a job or an interest in life. Neither is intelligent or educated enough to find either a new life offered in a profession or depth and self-awareness in what could possibly be a kind of Franciscan, Zen, or sadhu simplicity. Both are infected with juvenile and false images of success and happiness. Like those rusticating away in the scattered houses on the Texas plain, they cannot fathom why their lives are so empty and meaningless. Crying like a child, Breedlove wonders why “nothing ever worked out for him, he cried silently to himself, swallowing the sobs and trying to stop. Everything fucked up every time. Other people got away with murder. He couldn’t get away with shit” (363). He is too immature and self-involved to recognize that no one in Agatite gets away with anything. Life for everyone there is blank, dreary, and pointless. As Gwynn said, “Anyone who has spent time in a place like Agatite [...] will know that Imogene’s vigil is one that she does not endure alone.” She simply sits in public instead of in front of a television or in a church pew.

Imogene’s husband, daughter, and would-be lover, Ezra, are all too lively, too sexual. They want to drag her down to a carnal level, but she will have none of it, preferring instead to sit in public, priggish and prim, innocent of any and all tainted adult knowledge that would lead to compromise and accommodation necessary to build a real life. Little boys try to get away “with shit.” Little girls follow the rules and sit passively waiting for their daddies to compliment them on their primness. When Sheriff Holmes calls Cora’s father to inform him of his daughter’s disappearance, he says that, if she is not found, “she’s eighteen, free, and capable of making adult decisions—possibly more capable than her mother” (36). Those determined to make something of life get up and leave places like Agatite and the scattered hermit huts on the plains, even as Reynolds himself did.

In the “Afterword” Reynolds insists his novel is “a love story. It’s about the love a man can develop for a woman who has no love to return” (216). Most of the novel is concerned with Ezra Holmes’ efforts to locate Cora and plumb Imogene’s blank, unsullied feelings and vestigial thoughts. But like everyone in Agatite, Holmes is a failure. He suspects that Pete Hankins, the druggist, has been complicit in Cora’s disappearance, perhaps aiding her escape in exchange for quick sex. However, at most, Pete is a casual tool who had nothing to do with the mysteries of the McBride family. Ezra fixates nonsensically on him only because he knows him; he grew up with him and is shocked “to find out that there was a darker side to Pete’s nature than he had ever known, that his childhood buddy could lie to him so easily, so casually, so believably” (170). The sheriff blunders onto a liaison that Pete has with “Glenda Powell, a woman from town. Twice divorced, once from a Negro, she had a reputation that sent the hands of Christian women all over Agatite fluttering around their throats” (169). What kind of a sheriff is shocked to discover that his lifelong friend has sexual urges and is concerned about his reputation?

Holmes may not be shocked by Cora, but he is unwilling to accept her Aunt Mildred’s blasé assessment: “But it’s plain as day. My lands, a blind man could see it. She just run off. She never was any good. Too much money, too pretty. Too much like her daddy” (116). The shock here is to Ezra’s provincial understanding of the world; his recognition that escape from Agatite is that easy. The sheriff is also shocked, with ice-water dripping from his face, to discover how little he has understood Imogene after a year’s study. When he tells her that she does not understand his feelings for her, Imogene replies, “‘I understand more than you’ll ever know!’ Her voice was totally out of control, hysterical” (181). “You think every woman wants the same thing,” she accuses Ezra, her hysteria vapid and off-putting. “You’d do anything to get me off that bench and into your bed! Wouldn’t you? Wouldn’t you? Get away from me!” (182). Holmes solves no mysteries. “On his last day as sheriff, the day Abel Newsome replaced him officially he came out and sat beside her for a bit. They didn’t say a word to each other, and after a while he got up and left” (210). Imogene and Ezra sit like bookends knowing nothing but the mystery of their own diffident, feeble, and unfocused needs. With no ability in language or culture, they literally have nothing to say about their vacant lives.

In the last two paragraphs of the novel, the narrator suggests that Agatite offered refuge to Imogene. “It was a good life she had, she thought, not the one she might have chosen, but a good one even so. It was a good town, too. It was her town” (214). Can we accept this judgment? Imogene thanks Cora for abandoning her in Agatite and making her life of endless waiting possible. It is an emotionally retarded life without sex or love, without her unknown and discarded grandson. Her vigil resembles religious discipline, but there is never a hint of Meister Eckhart, Jacob Boeme, or even Thomas Merton—of some mystical tradition that would validate Imogene’s dedication as more than pathology. Imogene prepares bad food for strangers and returns to her bench, thinking “It was a way she had of renewing her hope” (212). Hope for what? If she has any hope, it resembles nothing so much as the vague and undefined hopes for “new life” offered by fundamentalist churches of the flat land that are themselves disconnected and in denial from the development of Western science, culture, and even theology. We are also reminded of Roy, who did not know what he hoped for from life, but knew to the point of murder what he would not accept. Despite Reynolds’ affection for his character and for the ugly town, the end of The Vigil anticipates Agatite’s “Prologue” in which the narrator despairs of life in a town that “seemed worn out, used up” and “merely a scar” on the highway leading elsewhere (2). The many reviewers of The Vigil were so taken with the psychological study of Imogene that they ignored how desolate the town is; so desolate that it finds Imogene’s vigil to be interesting, to be something that vaguely passes for culture in a place that is as vacant as Imogene’s life.

Monuments, the final installment in the Agatite trilogy, is the most hopeful of the three novels; or perhaps it is only that the violence in the novel is a kind of harmless Fourth of July display. For better or worse, Reynolds grows nostalgic in the third novel, confessing, “I want people to read it as a story about relationships, about fathers and sons and mothers and sons; about family and values” (Bettacchi). Mowing lawns has replaced agriculture. There is little more to do in Agatite than watch the grass grow. By the end of the novel, families have broken up and scattered, looking elsewhere for something meaningful to do with their lives. Reynolds’ protagonist, Hugh Rudd, is a fourteen-year-old boy. After suffering a mental breakdown, caused in no small part by living in Agatite, his mother, Edith, has gone to live near her parents in Corpus Christi. Hugh’s blond sweetheart, Linda—another of the Madonna clones—is going to Europe before beginning classes at Stanford University. Her father, Carl Fitzpatrick, once aspired to be mayor of Agatite and even governor of Texas, but has moved to California where his estranged wife is “in San Francisco, living with an artist” (368).

The palpable monument to which the title refers is the Hendershot Grocery Warehouse, “the tallest building in over two hundred miles” and “the only six-story structure of that vintage in the state.” It is “over eight decades old,” but “even those who spoke the loudest in the attempt to save it had to admit that it had long been an eyesore the whole town would be better off without” (3). The building is a symbol of the town, subliminally recognized as such by the people who rally to save it from being razed by the railroad. A monument to nothing, the building, and thus the town, is associated with death as a monument like those in a cemetery. Midway through the novel, “Hugh suddenly had the impression that instead of looking at his own downtown, his hometown . . . he was looking at some sort of grotesque cemetery” (208). The building has no use or function. Even if it were restored, at a cost of two million dollars, it would be largely useless and without any aesthetic or even historic value. Its original function, vaguely funereal, was to preserve produce and other foods as long as possible in a time before refrigeration.

Jonas Wilson, Hugh’s surrogate grandfather and Linda’s actual grandfather, claims to be nearly one hundred years old. He is elegiac about Texas small towns, saying that he helped build the monument. The novel, however, does not celebrate the monument; rather it records the building’s destruction and Jonas’s death when the building is blown up. Wilson rhetorically asks Hugh about local history, “How ’bout Hoolian, Pease City, Naples?” He tells the boy, “Well, all them was towns, and there was more besides: Goodlett, Franklin’s Crossing, Squaw Creek Store, Medicine Lake, Milltown, Apex, Piss Ellum Church.” Wilson lectures that the “day of the small town is done,” because “folks moved here [to Agatite], or they moved somewheres else. Sooner or later, folk’ll move away from here, too. Sooner or later, this’ll be just a wide spot in the switchgrass, and then the mesquite’ll come in and take it over just like it done all them other places.” He explains, “When I was your age, most boys just stayed right where they was” because the world was more primitive offering few opportunities for anything more than subsistence agriculture (213). Consequently, “places like this was good ’nough for folks once upon a time. But that time’s done.” Trying himself to preserve a way of life that is dead and past, old Jonas wisely counsels the boy, “Don’t be fretting over it” (214). “That’s the way of things. Ain’t nothing built forever” (212). Who would have expected Reynolds to give us a character like Basho offering Buddhist advice in West Texas?

By the end of Monuments, the town has come full circle. Its purpose had been to service the agricultural economy: to distribute agricultural technology delivered by the railroad and to ship agricultural products to distant cities via the railroad. However, the only agriculture evident in the Agatite trilogy is Hugh’s lawn mowing and Jonas’s luxuriant truck garden. Hugh claims that Jonas’s garden—and hence the earlier agricultural life it represents—is “better than mowing lawns” (373). The Garden of Eden becomes an ironic legacy left by the town loony. “Improbably running a kind of combination sporting goods store and fishing guide service” (370), Hugh’s father, Harry, reverts to the pre-agricultural frontier stage of development antedating Jonas’s efforts at something like the Granger Movement, which dreamt of socialized farming to perpetuate Thomas Jefferson’s idealism about those who create from the earth itself.

In contrast to the adventitious politicians, Jonas was a union organizer; “in the twenties and thirties, he went all over and tried to organize workers into unions. He was a member of the I.W.W. before that” (377). Reynolds, with a B.A. in history, explains something of the Wobblies to make sure readers recognize Jonas’ pedigree. “He was a pacifist, too” (247), even if he did attempt to clean the temple by slugging the railroad agent, Grissom (378), who is bent on destroying the monument and town in order to build a switching station to allow trains to turn around from the dead-end of Agatite to go back to wherever they came from. Early in the novel, Hugh asks Jonas, “You ever hear of a man named Thoreau?” West Texan that he is, Jonas deadpans, “Live ’round here?” (98). The monument of Jonas’s life and the legacy of his garden suggest both Voltaire’s advice to Candide, to tend his own garden, and the example of Walden Pond but none of the characters in the three novels is educated enough to recognize the allusions and irony.

Linda, eighteen at novel’s end, returns to Agatite after being away for four years. Hugh takes her to Jonas’s garden as though to a cemetery, where she asks, “I mean, here you are, keeping this stupid garden going, feeding that stupid dog. And why? It’s because of him, isn’t it? Because of that silly, stupid old man. It’s like you brought me out here to show me what a great job you’re doing keeping it all alive. That’s it, isn’t it?” (375). Hugh is too young and too struck by Linda’s beauty to say that the garden is a symbol of the continuity and renewal of the values that Jonas dedicated himself to throughout his long life and perhaps a vague offering to her, an offering that suggests the garden they could grow together renewing love and life in small town Texas. Hugh insists that Jonas literally saved his granddaughter when the Hendershot Grocery Warehouse and “monument” was dynamited, and that he figuratively saved both youths by initiating them (or at least Hugh) into the recognition of a deeper, more authentic life. But Jonas has no heirs.

The lesson is lost on Linda who is ironically in Agatite only for a brief visit before touring the monuments of Europe. She asks Hugh why he risked his life to save her. “You thought if you saved me, I’d fuck you, right? Give you what you wanted but didn’t have the guts to take even when I was trying to hand it to you? Was that it, Mr. Baseball Stud?” (375). Linda’s coarseness undercuts her observation and reminds us a bit of Imogene’s sexual hysteria, but there is still a knife cut of disgust aimed at wasted opportunity and timidity in her remark that the legacy of Jonas’s life is Hugh’s “demon. And I guess you’re dealing with it the best way you know how” (376). Hugh’s gesture of maintaining Jonas’ garden is clearly related to Imogene’s vigil and more tenuously to the fundamentalist religious hope for a “new life” in some recovered Eden. None of them know quite what they hope for or where that Eden might be and consequently have no idea of what to do in life.

Jonas is hardly the typical resident of Agatite. He lives on its fringes in a boxcar. Hugh correctly calls him a hermit. Much like Socrates in Athens, Jonas is a problematic role model or monument suggesting what a citizen of Agatite should be. In a clear echo from Socrates’ trial, Hugh’s mother charges that Jonas “leads young people astray. Ruins their lives” (226). It is all very well for Diogenes to live in a bathtub and for Jonas to live in a boxcar, but neither pays taxes or is a state-licensed teacher. How can Hugh, or anyone, follow in Jonas’s footsteps? This question is repeated in the book’s final image. Linda invites Hugh to write to her, and there are hopes of romance. Hugh wonders, “What was the name of that dormitory?” And then he shakes his head. “‘It don’t matter,’ he heard a familiar voice in his mind speak [...]. ‘Some things are just best forgotten’” (382). The voice is, of course, Jonas’s. The voice does not bless a marriage between his two grandchildren that might produce another crop of Agatite citizenry; to the contrary, it advises Hugh to forget the struggle to preserve or renew the town.

Reynolds deftly skirts questions of continuity, conservation, legacy, and Chamber of Commerce talk about bringing in new jobs to enhance the quality of life in small towns. He avoids them by putting forth Jonas—a kind of displaced philosophy professor lacking a university—as Agatite’s best citizen in contrast to the war hero Phelps Crane. “Phelps is the one bears watching,” Jonas says. “He’s never been much account since he come back from the war [World War II] with all them medals” (198). In one of his longest and most incisive speeches, Reynolds has Jonas preach,

Most of the people in this world who have money’ll run you into the ground getting more of it, run you into the ground keeping you and anybody else from having it, and the whole time they’re doing that, they’re running scared their own selves. They don’t care ’bout nothing else but that, and every day of their lives, they get up expecting to find their walking papers in their pay envelope. They got no pride, they got no shame, don’t care ’bout how good a thing is, ’bout how long it might last, ’bout what it might mean to some folks. They’re just getting through the week walking on somebody else’s backside, and they’ll smash you like a rotten ’mater [tomato] if you get in their way.” (78)

This judgment is arguably truer about small town life than urban life. In fact, Reynolds says that in small towns “There’s a kind of brutality there that urbanites for all their ghettos, barrios, and crime can never understand,” perhaps because the rusticated often know each other from childhood and because there is no compensation offered by professional life (“Profits” 57). After concluding his speech, Jonas announces, “Got to tend my garden. Take care of business” (78). The allusion could equally apply to the rustic and hermitic Thoreau or to the sophisticated Parisian Voltaire or to Elvis Presley, whose motto was TCB— “taking care of business” (see Reynolds, “Elvis and Us”).

Like the great regionalists Wright Morris (Nebraska) and Eudora Welty (Mississippi), Reynolds set out to discover what is unique or special about small town life in Texas only to find out that what Faulkner called the verities of life are universal. Reynolds confesses, “The small towns of West Texas [...] are less places, than they are collections of souls. Some of the best souls found peace in the cemeteries there. Some fled never to return. And some are still there” (“Profits” 56). Reynolds’ fiction is often violent, or it stalks an anticipated violent climax in unconscious hopes of revealing something profound that does not require professional dedication and investment, but simply is. One symptom of this social deprivation can be found in millennialist churches that preach about the Rapture. In the medieval world, a “new” religious life required the life altering decision to enter a monastery or convent and to follow a rule of discipline. Calvin offered an abstract version of this process centered on vocations in the world, but discipline remained a key requirement. Reynolds’ characters long for the beautiful and authentic, for lives of purpose and pride, but they have no cultural methods or institutions that could help them realize these dreams. Consequently, they have no idea about what to do beyond waiting for the Rapture, waiting to win the lottery, or waiting for something unimaginable to happen that will change their lives.

Monuments offers a model in Jonas, the pacifist whose principles seem to have emanated from Karl Marx by way of the I.W.W. rather than from the stark and unforgiving Christianity that infuses West Texas where guns, intolerance, and church form what passes for culture. In this context, Jonas is too literary to serve as an exemplar. Just as the vacant plains offer only a vitiated notion of religion, lacking any institutional and historic form, the region offers only the rudest form of Main Street education, which would ridicule Jonas as a bumpkin or town lunatic instead of recognizing him as a sage. “He’d set up a soapbox downtown and make speeches about the evils of capitalism on Saturday afternoons. He was a pacifist, too.” During World War II, Jonas preached “about how we didn’t need to be fighting the war, about how it was all a crooked scheme” (378).

Monuments suffers from self-consciousness as the novel that completes a trilogy. The old hermit Jonas is almost a reincarnation of Carson Colfax who appears in Franklin’s Crossing. Jonas is a Wobblie prophet without Colfax’s colorful cursing; he is Woody Guthrie living in a boxcar without wheels, the authentic steward and tender of the garden whose literary neighbors are William Bradford, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and John Muir. In the first two novels of the trilogy, Reynolds emphasizes whatever is positive or even suggestive about life in West Texas, but in Monuments he tries too hard. There is a Booth Tarkington lilt to the novel that is gratuitous, arising no doubt in part from using a fourteen-year-old Tom Sawyer character as the protagonist. But it also comes from an attempt to memorialize the first two novels and claim that something good or enduring may come from the tedium, the heat, and the occasional violence of life in the lost little towns of West Texas. Looking back on the novels, we are reminded of Joseph Conrad’s “Youth” and the recognition of how the optimism of youth finds value and hope in virtually any circumstance.

Consider the last paragraph. Having decided to forget his blond virgin, Linda, eighteen-year-old Hugh remembers that his dad “was grilling steaks that night. They would eat them and watch the Rangers take on Detroit. Maybe drink a beer or two” (382). Beef, beer, and baseball without the ache of alluring blond beauty. This is close to parody. Reynolds’ nostalgia notwithstanding, this is not culture, and it does not offer more than a stunted quality of life without beauty (women). This scene is pacific only because it is nostalgically juvenile. Having Hugh so easily forget the blond goddess Linda to think of baseball strains our credulity. We can easily imagine Hugh ten years older as a character in one of Reynolds’ short stories, drinking with his pards as he careens through the dusty back roads in a beat up old pickup searching for something to kill, searching for an escape from something he cannot name, and succeeding only in exploding in some act of senseless violence in hopes of erasing the recognition that beauty called him and he funked the response because he had no cultural preparation to sensitize or prepare him for such a moment.

Reynolds’ trilogy is not fundamentally about violence. It is about a lack of imagination and daring, about a puritan fear of beauty, and about a withering of frontier ambition and enterprise. His characters become violent in their desperate and irrational hope to do what? Like Imogene, they only spend another day on a bench waiting for something to happen; or like Roy Breedlove, they catch a bus to another town that is indistinguishable from the one they just fled. Reynolds’ characters are too simple and unlettered to understand that they hunger for beauty, that they hunt beauty. The frustrated young men from the flat lands of West Texas engage in violence, unaware that they are hunting beauty’s reverse image. They are haunted by young, blond Madonnas—from Cora whom everyone waits for in The Vigil to the abandoned Cassie in Agatite whom Reynolds presents as Roy Breedlove’s medieval virgin amid the carnage in the Agatite bank robbery. She is “the child that had become the symbol of his guilt” (365-66); all his life Roy flees the image of beauty he is too frightened to embrace. Even Linda in Monuments takes on mythic dimensions. She is the granddaughter of an authentic prophet, Jonas. Hugh may forget her college address, but he will dream of her long after he is bored by baseball. Four years after their ordeal in the imploding warehouse, Hugh unexpectedly sees her in the Agatite drugstore. “He almost became dizzy. His eyes ran uncontrolled up and down her form.” Hoping to sound mature and world-weary, Linda says, “I mean, Jesus Christ, Hugh, this is still my hometown” (367). It is easy to mistake this coarse voice and Linda’s stunning beauty for the character Jacy in McMurtry’s The Last Picture Show (played in the movie by a young, gorgeous Cybill Shepherd).

For Reynolds, beauty is still the idol of West Texans, though they may try to deny it with their puritan talk of crucifixion, being dipped in the blood of the lamb, and Rapture. Perhaps the best feature of Reynolds’ fiction is found in the recurrent pattern of tongue-tied and not very bright good old Texas boys courting the mystery of beauty they cannot understand nor resist. The icon of the blond Madonna may be repeated too frequently. She is also too stereotypical. In contrast, Reynolds’ male characters display both regional verisimilitude and enough psychological depth for us to feel that we know them, and perhaps their region, better than they know either. Whether from his love of theater or hopes for movie contracts, Reynolds has an exasperating penchant for complex plotting, for offering a mystery at the beginning of a novel that takes at least three hundred pages to explain. In Agatite the mystery is not so much that of Eileen’s murder, but Roy Breedlove’s character. The mystery of who Breedlove was necessarily becomes a regional study of West Texas small town life.

Reynolds best work illustrates the importance of region; how where we live is largely the answer to who we are. We care about common folks living in Agatite far more than we do about the flashy and cheap characters in Reynolds’ Players or the grim pioneers of his Franklin’s Crossing, because we know so much more deeply where they live, how they live, and consequently, who they are. Reynolds’ mistake (or that of his readers) is to expect a social and cultural renewal in the small scattered towns of West Texas that were founded in a simpler time. These little towns could not possibly have developed the social resources—universities, laboratories, and high-tech industries—that would renew the hope and optimism of their founding to offer satisfying professional lives to young adults. The literal legacy in Monuments is an empty building with no use or history. The figurative legacy is personified by the blond Madonna who suggests that the authentic legacy of any community is found in its art, which offers the record of its response to the beauty offered by life. In this sense, the Agatite trilogy is itself the legacy of the small towns of West Texas. Reynolds may not surpass Larry McMurtry as the artist who best renders a region of Texas, but the comparison offers praise enough. The Agatite trilogy is an accomplished work that will be read for many years by anyone interested in regional literature.

Bettacchi, Betty. “UTD Professor’s Latest Novel Takes a ‘90s Twist in Tale of Texas Teen’s Angst” (Monuments review), Richardson News (Texas), Sunday, July 9, 2000: 3B.

Carden, Gary. “Action Boils in Heat of Tiny Texas Town” (Agatite review), Asheville Citizen Times (North Carolina), August 16, 1987: no page number.

Dalrymple, Terence. Agatite (review), New Mexico Humanities Review, 10.1 (Spring 1987): 90.

Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying. New York: Vintage, 1930.

Gwynn, R. S. The Vigil (review), Texas Writers’ Newsletter, 43 (May 1986): 43-4.

Long, Russell C. Agatite (review), Texas Writers’ Newsletter, 45 (January 1987): 45-6.

McMurtry, Larry. Texasville. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987.

Reynolds, Clay. Agatite. New York: St. Martin’s, 1986; New York: rpt. [as Rage] Signet, 1994.

________. “Elvis and US,” High Plains Literary Review, 10.3 (1995): 21-35.

________. Monuments. Lubbock: Texas Tech UP, 2000.

________. “The Profits of Place: Using a Lie to Tell the Truth,” Texas Journal, 19.2 (1997): 48-57.

________. The Vigil. New York: St. Martin’s/Richard Marek, 1986.

![]()

|

|