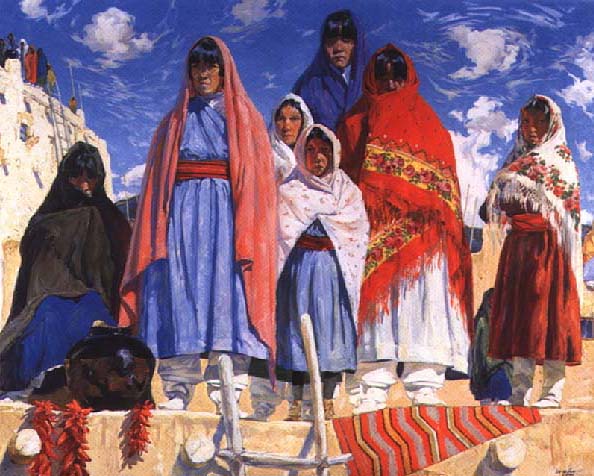

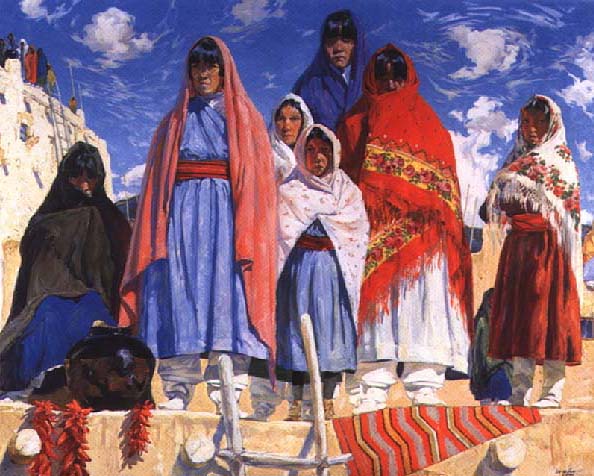

Their Audience, Walter Ufer, 1917 (Snite Museum, Notre Dame)

nau | english | rothfork | publications | James Steele, Frontier Army Sketches

Their Audience, Walter Ufer, 1917 (Snite Museum, Notre Dame)

James Steele: New Mexico's First Local Colorist

This essay was published in The Midwest Quarterly, 21.4 (Summer 1980): 484–92.

James Steele's

Frontier Army Sketches (1872-3) provides an interesting example of the

failure of regionalism in the Southwest. As a casual observer of New Mexico for

several months,

Steele disparaged the native Indian and Mexican cultures

and

advocated a stronger military regime to eradicate the Apaches and hasten the

progress of Anglo culture. Steele was a man of his age, respecting technological

progress and advocating post-war expansion in the West. Consequently, he saw the

native cultures of New Mexico as nothing more than impediments to progress and

advocated the uniform adoption of Anglo customs by everyone. There is nothing

original in any of Steele's ideas, but for this very reason his book has

historical value. More importantly, as the first writer to attempt a

Southwestern

regionalism, Steele demonstrated the problems with it, which have

never been solved, and suggested a nationalism that proved to be somewhat

prophetic to New Mexico, if not to the West in general.

Steele was born in Illinois in 1840, spent his childhood in Topeka, and began

college in Indiana. But in 1861 he left to join the Union Army and served until

1863 as a clerk in a Nashville military hospital. Because of illness, he left

the army for a year, but received a commission in 1864 and served another year,

seeing action and being wounded. Like other postwar veterans, he was bored with

civilian life and in 1867 rejoined the army to serve in Kansas and New Mexico

for three years. Then, back in Topeka, Steele helped found the Kansas Magazine

and supplied twenty-three sketches for its first three issues in 1872-3.

Eighteen of these were collected in The Sons of the Border, a title which

Hamlin

Garland only slightly changed in his

Son of the Middle Border. Over the next

twelve years, two variant editions appeared, West of the Missouri and Frontier

Army Sketches.

The first sketch of the book, depicting a young frontier army officer, casts its

shadow over the whole, with Captain Jinks or his type making at least cameo

appearances in most of the other tales. In other sketches, Steele portrays

cowboys, miners, gamblers, pioneer women, Apaches, and Pueblo Indians, as well

as army mules, buffalos, and coyotes, but it is clear from the outset that the

army officer is not "a mere frontiersman like the rest," but is "what, for want

of a better name, we call a Gentleman."

Steele begins his sketch of Captain Jinks with some mild satire on "his very

foolish airs," which is reminiscent of

Colonel Simon Suggs and illustrative of

local color humor. Like a Southern gentleman, "Jinks is somewhat frivolous,

over-polite, and nonchalant, and carries a very high nose." To balance this he

has Yankee business acumen fostered by Army bookkeeping and responsibility "for

all the houses, fuel, forage, animals, tools, wagons, and scattered odds and

ends of a post as large as a respectable village." Furthermore, an officer "is

like an autocrat and justice of the peace" who combines the offices of

"physician, priest, and executor." While in the "changeless empire of monotony

and silence," which is the desert, he is a Stoic explorer, but at the military

post¾which Steele never fails to

idealize as an altar of Eastern civilization¾"Jinks is something of an epicure." And it is in this antagonism

between Stoic and Epicure that we first see the antagonism between the

undeveloped wilderness of New Mexico and what Steele believes it should be under

the tenets of

Manifest Destiny . Steele sees the New Mexico landscape as "a world

of loneliness and lost comforts, where cities, banks, railroads, theatres,

churches, and scandals have not yet come." To the young officer, the vastness of

the barren landscape was an affront to the grandiloquent rhetoric of progress

and the excitement of the recent war. Consequently, "the days, unchanged by the

ceremonies and observances of civilizations, are all alike, each as melancholy

as a Puritan Sabbath."

This is not to belittle the suffering of Steele, who had led troops of the Army

of the Potomac into battle and now faced boring duty in isolated desert forts,

but to suggest that far from having an attachment to the land, Steele had reason

to hate it. In fact, it was this intolerable duty that caused Steele to resign

the army career that he so obviously desired. Therefore, Steele was in the

strange position of writing about a land in which he not only had no roots, but

which he actually resented, "a land where nature in all her forms seems to

delight in coarseness and ruggedness." Steele even went so far as to ignore the

blue sky and call it "a dreary land." Moreover, Steele was nearly compelled to

exaggerate the importance of the land because of the conventions of local color,

which were fast becoming, if they were not already in the 1870's, a series of

formulas that dictated how frontier material could be used in the Gilded Age. In

fact, the adherence to the clichés of local color demanded by the Eastern

publishers retarded the development of an authentic regional fiction in the

Southwest, which like other regional literature had to grow out of an intense

relationship with the land and its demands for survival. The regionalist

explores how the land subtly

influences the unconscious development of a culture. To be aware of such

subtleties, the author almost has to be a member of that culture or subculture.

In contrast, Steele simply reviled the Apaches and thought Mexicans were at best

quaint. Genuine regionalism usually asserts that a local community order has

reached a harmony with the land that is superior to the larger order that has

lost its roots in dealing with abstract problems. As a member of an occupying

army, Steele saw none of this. His commitment was to the pseudo-community of the

army and to the arbitrary solutions provided by a force of arms. For example,

Steele saw no irony in this boast that Jinks remained insensitive to his

environment and destructive to the indigenous cultures: "From whence does Jinks

derive the mysterious quality that enables him to survive the crudest

associations, the wildest surroundings [...]

and still remain the inimitable J inks¾clean, quiet, nonchalant, transforming

the spot where he is bidden to abide, changing all the sensations of the place

where he has pitched his tent?" Steele suggests that this "mysterious quality"

derives from a blind loyalty to Manifest Destiny which causes the officer to do

"his whole duty in camp and field" oblivious to any local variations.

The most obvious duty of the officer is to kill Indians, who Steele endlessly

assures us were idealized by

James Fenimore Cooper. In actuality, they are

"filthy, brutal, cunning, and very treacherous and thievish." The Indian has a

quality of moral degradation which is "inborn and unmitigated." He has no

concept of a proper home and no notion of occupation. The Indian woman is as

beautiful as a gorilla: "squat, angular, pig-eyed, ragged, wretched, and insect

haunted." Moreover, "she is stoop-shouldered, bow-legged, flat-hipped, shambling,

and when at last she dies, nobody cares." Indian children are full of "malice,

cruelty,

filth, ill-temper, and general hatefulness." Indians have "no strictly religious

forms" and "nothing that is regarded as especially sacred." The medicine man is

distinguished as being "if possible, idler, raggeder, and lazier" than the

others. Steele believes that Indians do not have a proper language, and "in lieu

of a complete vocabulary they use many signs."

Taken out of context, these pronouncements may seem to be examples of local

color exaggeration. But in the context of the sketch and juxtaposed to the

realistic treatment of frontier hardships and the romantic praise for helpless

frontier women, Steele's hatred for Apaches is unequivocal. It was also typical

of its time. For example, it would be hard to surpass the hatred of Indians

found in

Nick of the Woods (1837). Another indication of Steele's ingenuousness

is found in the naive boast that "there are many men on the border who earn a

livelihood by outwitting the Indian at his own game." Apparently they must have

been better Indians than the Indians, just like Cooper's

Natty Bumpo. It was too

bad no one told

Geronimo whose ragged band of thirty-six men, women, and

children long evaded five thousand army troops. Finally, Steele was serious in

his contention that anyone who did not hate Indians simply did not know them

like the cavalry officer.

Shortly before Steele's tour of duty in New Mexico,

Colonel Kit Carson and

others led a campaign against the

Mescalero Apaches and the

Navajo. The Indians

were captured and imprisoned at

Fort Sumner. The

Navajo and

Apaches, mutual

enemies, were kept together as prisoners of war for five years while the

bureaucrats argued their fate. The military wished to remove them to the

Oklahoma Indian Territory and make them self-supporting farmers like the

Pueblo

Indians. But as the cost of maintaining nine thousand Indians grew, economy

dictated their repatriation in their traditional homeland. Although Steele was

in New Mexico during the last year of the imprisonment and when the Navajo

walked back across the state, he was never directly involved with these

operations.

Despite all the well-reasoned hatred, Steele acknowledged that the Indians were

victimized by treaties and "unscrupulous commerce," but judged these to be

insignificant in the fact of inexorable "migration from east to west," which was

"the sentence of doom [...] written against the red man, slow in its operation, but

utterly irrevocable." Seeing the virtual disappearance of Indians from east of the

Mississippi, Steele, like the military and other Indian experts, thought it

logical that they would also disappear from the West. Since there was no place

for them to go, they would simply have to become as extinct as the

buffalo.

After the litany of horrors regarding the Apaches, it is a bit of a shock to

find that Steele thought there was a "Good Indian." Indeed he said that "the

Pueblo is only an Indian by the general classification." The chief virtues of

the Pueblos that led to this estimation were their agricultural pursuits and the

fact that they were "the only ones of the original races who have always been

friendly to the white man." Steele thought that they were doomed by progress,

but that "when the poor Pueblo shall finally leave his seed to be sown with a

patent drill and his harvest to be reaped with a clattering machine, he will

merit at least the remembrance that his hands were never red with Saxon blood."

In "New Mexican Common Life" we find that the Mexican "is remarkable only for

placidity." "To dance and smoke seem to be the two great objects of Mexican

life," and Steele speculates that Catholicism has made the race docile and

cowardly. In other stories, Steele tells us that even "Mexican women of the

better class" are "ignorant of all nerves and proper sensations," and

that in a crisis a Mexican woman will go to pieces "praying rapidly after the

fashion of her race." The men "are not of that class who of their own accord

long for freedom" and consequently, "the alert and vivacious Saxon has

established himself at the corner of every street in his chiefest villages."

These characterizations are, of course, offensive, but no worse than other

newspaper prose and popular novels of the period, and they are historically

accurate records of Anglo attitudes. There are also infrequent scenes of realism

which, unlike Garland, Steele never developed beyond poignant scenarios. For

example, consider this realistic and common frontier sight: "the grotesque

procession of lean and melancholy cows, multitudinous and currish dogs, rough

men and barefoot girls, and, lastly, the dilapidated wagon, with its rickety

household goods;" or the despair of the miner and gambler: "that look upon faces

that tells of the homelessness of years, the days of toil and sacrifice, the

months of delving and hoping, all gone in a single night." Unfortunately, Steele

did not recognize the potential depth in scenes like these and blithely pursued

the jingoistic prose of Manifest Destiny. Consequently, his use of local color

remained superficial and mechanical, displaying none of the shrewd and sardonic

insight into character of Mark Twain or Bret Harte.

The interest of Steele's book is that it illustrates the problems of local color

and regionalism in the Southwest and proposes a strange, if not impossible, blend

of the local and national. In his fine essay, "Regionalism in American

Literature," Benjamin Spencer suggests that the diversity of cultures in the

Southwest has retarded a regional consciousness and that "the

Anglo-Spanish-Indian elements have not been culturally fused even to the degree

that the Anglo-Negro elements have been synthesized in the Southeast." The

diversity among Leslie

Silko's

Ceremony, Edward

Abbey's Fire On the

Mountain,

and

Rudolfo Anaya's

Bless Me Ultima, illustrate that the

mosaic of cultures in

New Mexico is unlikely to coalesce into a single regional voice. Steele's

solution was simply to belittle all the cultures except the Anglo. His frontier

local color was actually an extension of the frontier ethic, which after the

Civil War produced the

Robber Barons; it was simply exploitative. Whatever the

region possessed was conceived as raw material for the nation. Even the idea of

wilderness became a commodity in the rhetoric of Teddy Roosevelt. And in fact,

there is some parallelism between Steele's and

Roosevelt's thinking. Certainly

Teddy would have thought some of Steele's fiction "bully," not least of all the

idealism of the frontier cavalry. Finally, there was some curious prophecy in

Steele's nationalism. For the largest social industries in New Mexico are

creations of the federal government: The Forest Service, Bureau of Land

Management, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Los Alamos Labs, Sandia Labs, White Sands

Missile Range, Kirtland and Holloman Air Force bases; while the physical

industries continue to be exploitative: gas, oil, uranium, and other mineral

extraction. Nor has there been any real progress in communication among

cultures. There has been a general erosion by the dominant Anglo culture and a

continued silent resistance and isolation by the most traditional elements in

Indian and Spanish cultures.

So Steele, the first to attempt to evoke the regional uniqueness of New Mexico,

was the first to fail. And while the state has had many voices, none of them

spoke for the whole, nor is it likely that anyone can. What is strangest is that

the national identity that Steele foresaw would supersede a regional identity

has occurred, not in the jingoistic way Steele thought, but as the only unifying

identity for otherwise diverse cultural groups.

![]()

Biographical information on James W. Steele was taken from the introduction by Philip D. Jordon to Frontier Army Sketches (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1969).

![]()

|

|