Baseball is a funny game, you can spend a career failing 7 out of 10 times and still find yourself in the hall of fame as a .300 hitter. But to spend a career failing 6 out of 10 times and have a .400 batting average is impossible for even the most legendary of hitters.

Baseball has withstood the test of time, weathered many storms (though often self-imposed), and has cemented itself as a classic American institution. Although baseball is no longer the only professional sport with mass appeal, some of the best athletes of our time can be found within stadiums that often act as houses of worship for the American masses.

To those who choose to listen, baseball teaches about motivation and hard work; about love and heartbreak; about victory and loss. Playing as a child helps teach social skills, values, and introduces the Little Leaguer to much more than a game played on a patch of grass. The game grows alongside those who choose to engage with it, providing generations of Americans the same simple, but crucial, pleasures - hope, community, and the belief in a better tomorrow. Fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers summed up the beauty of the game best in their unoffocial rallying cry, "Wait 'til next year".

The Chosen People and America's Game

Throughout human history the Jewish people have long suffered from antisemitism and mistreatment, but that history has not been without heros. Starting in the early 1900s as Jewish immigrants from around the world continued to make their way to the United States, it was baseball that would eventually help them find their place in American society. Baseball, and its numerous variations, could be utilized to teach values and help establish an American identity within its players. As the Jewish population in America continued to rise throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and in response to the resulting increase in antisemitism, older generations of established Jewish-Americans began to fund and operate Settlement Houses. They hoped to support the newly arrived immigrants and ease the culture shock of moving from the old-world shtetls to the over crowded and expanding American east coast cities. Opposed to most parents wishes, "settlement house workers, teachers, and other youth workers encouraged Jewish boys to participate in baseball, which they beleived was one of the best means to acculturate newcomers into the host society's value system," (Riess, 1985. P214).

As well as encouraging Jewish acceptance and integration into American culture, baseball also provided opportunities for American culture to have exposure and interactions with Jewish individuals, resulting an a mutual acceptance by both sides, and the creation of a dual Jewish-American identity.

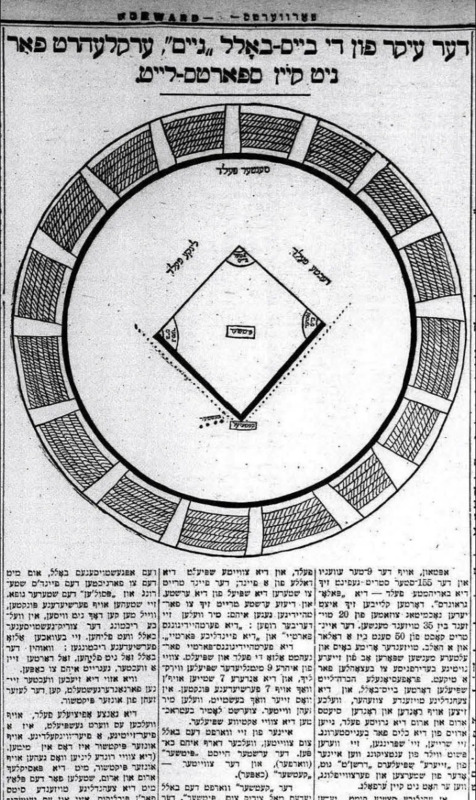

While children happily joined in the game, adults were less than impressed. Coming from a world of hard labor and study, to the newly arrived immigrants the notion of running around playing a game was as foreign as the rest of this country. To the right is an attempt by Abe Cahan to extend the new found appreciation of the game to parents.

The article titled "Fundamentals of the Base-ball 'Game' Described for Non-Sports Fans" was published on August 27, 1909, and perfectly captures a lack of nuanced understanding of the game, but a clear acknowledgement to its importance in American life.

A translation of the article reads;

............

To us immigrants, [Baseball] seems crazy, however, it’s worthwhile to understand what kind of craziness it is. If an entire people is crazy over something, it’s not too much to ask to try and understand what it means.

We will therefore explain here what baseball is. But, we won’t do it using the professional terminology used by American newspapers to talk about the sport; we must apologize, because we’re not even able to use this kind of language. We will explain it in plain, “unprofessional” and “unscientific” Yiddish.

So what are the fundamentals of the game?

Two parties participate in the game. Each party is comprised of nine people (such a party is called a “team”). One party takes the field, and the other plays the role of an enemy; the enemy tries to block the first one and the first one tries to defend itself against them; from now on we will call them, “the defense party” and the “enemy party.”

The “defense party” also takes the field and plays. Two of the team players play constantly while the other seven stand on guard at seven different spots. What this guarding entails will be described later. Let us first consider the two active players.

One of them throws the ball to the other, who has to grab it. The first one is called the “pitcher” (thrower) and the second is called the “catcher” (grabber).

Each time, the “catcher” throws the ball back to the “pitcher.” The reader may therefore ask, if so, doesn’t it happen backwards each time – the catcher becomes a pitcher and the pitcher becomes a catcher? Why should each one be called with a specific name – one pitcher and one catcher?

We will soon see that the way in which the catcher throws the ball back is of no import. The main thing during a game is how the pitcher tries to throw the ball to the catcher.

The enemy party, however, seeks to thwart the pitcher.

This occurs in the following way:

One of the team’s nine members stands between the pitcher and the catcher (quite close to the catcher) with a thick stick (“bat”) and, as the ball flies from the pitcher’s hand, tries to hit it back with the stick before the catcher catches it.

This enemy player is called “batter.” The place where he stands is designated by a number of little stars (****).

(The other eight players on the enemy team, in the meantime, do not participate. They each wait to be “next.”)

Imagine now, that the “batter,” meaning the enemy player, finds the flying ball with his stick and flings it. If certain rules, which we will discuss later, aren’t broken, this is what can happen with the ball: if one of the “guards” catches the hit ball while it is still in the air, then the opposition of the “batter” is completely destroyed and the batter must leave his place; he is excluded (he is “out”). He puts down the “bat” and another member of his party takes his place.

The roles of the seven guards of the defense party are also specific: they must try and catch the hit ball in order to destroy the enemy’s attempt to hinder them and to get rid of the player doing the obstructing. They stand at various positions because one can never know in which direction the ball will fly. They watch the different trajectories in which the ball might fly, so a guard can be there, ready to catch it.

The readers can see the way the seven guards are distributed in our picture.

The entire official field on which the game is played is a four-sided, four-cornered one. This is in the center of our picture (The two round lines which go around it represent the tens of thousands of seats for the audience. That is how it usually is for the big professional games. It actually looks like a giant circus with a roof only for the audience. The field, with all the players, is under the open sky.).

As the readers see in the image, one corner is taken by the “catcher.” The other three corners of the four-cornered figure are stations. Each one is called a “base.” With the catcher facing the pitcher, the first “base” is outward from the direction of his right hand, just opposite him is the second base; and from his left hand is the third base.

A little bag of sand lay on every base. The guards, however, must not stand on the base, but next to it.

We previously mentioned three guards. They are called the first baseman, the second baseman and third baseman. A third guard stands between second and third base. He is called the “short stop;” when a ball is hit, it often goes in that direction and the “short stop” gets a chance to catch it in the air.

But if the ball flies way over the heads of these four “guards,” there are three other guards who stand on the outside field, or the “out field.” One of these is called the “right fielder,” the second, the “center fielder,” and the third, the “left fielder.”

Two of the four sides of the four-sided figure in our picture are marked with dots. When a hit ball flies over one of these two lines, it is called a false ball (foul ball). For it to be a proper ball (a fare ball), it must fly forward, or over the other two lines of the four-cornered figure.

When the batter doesn’t manage to hit the ball with his stick, it is called a “strike.” If he gets three “strikes,” he is “out,” or eliminated. Certain kinds of “foul balls” are considered “strikes,” however, we will not go into these details.

When the batter hits the ball and it is “proper,” and the guard doesn’t catch it, this means that the opposition, in this case, is successful. However, this success can either be greater or smaller. Depending on the level of this success, the following is done: as soon as the batter hits the ball, he throws his “bat” away and starts running; if nothing disturbs him, he runs to first base, from first to second, from second to third, and from third to the place where the catcher stands. This place is called “the home.” If he gets to the “home” spot, it means that the success of the opposition is complete.

This means that he made a whole “run:” and, based on these “runs,” the results of the game are figured out. The party which makes more runs is the winner.

But to make a full run at one time doesn’t happen all the time. In order to do so, the zetz that the batter gives the ball must be especially successful. It happens more often that he makes a quarter run, or a two quarter, or three quarter.

The rule is this: the running batter has no right to go to first base if the guard (the first baseman) holds, at that very moment, the ball in his hand. If the hit ball falls on the ground and one of the guards picks it up, the running batter is not yet eliminated. He runs. But imagine that some guard throws the ball to the first baseman and that this first baseman catches the ball before the running batter physically arrives at first base: then this runner is eliminated. But if he catches the ball when the runner is already on the base, the runner is “saved” (safe).

If the runner keeps running to second base, the rule is a bit different: the second baseman can eliminate him only if he touches him with the ball; and the same rule works for the third baseman, he has to touch him with the ball in order to get him out. The catcher or pitcher can also get a runner out with a “touch” if he finds himself near the base or the “home” to which he ran.

Each player is the embodiment of agility, with strong, swift muscles and sharp, fast eyes. And the whole game is full of “excitement” for those who are interested in it.

(Translation provided by Eddy Portnoy of Connecticut's Temple Beth David)

Curatorial Statement

The curation of this exhibit was not without its challenges and opportunities. The number Jewish ballplayers in the history of Major Leage Baseball is unsurprisingly low, but the experiences of those individuals often rival folk legend. Growing up a baseball-loving, very proud Jew, I frequently heard stories of Hank Greenberg almost breaking Babe Ruth's single-season home run record, and of Koufax not pitching in Game 1 of the World Series. There are many more significant stories from the careeers of those two ballplayers, further establishing both as icons in Jewish-American history. The respective and connected legacies of Greenberg and Koufax, through the lense of supporting the establishment of the dual Jewish and American identites, is further explored in this exhibit.

During their careers, Greenberg and Koufax served as heros to Jewish-American children across the nation. However, Jewish-Americans were heavily involved with the game off the field as well. Most recently the first Jewish Commissioner of Baseball, Bud Selig, oversaw the modern adaptations to bring revitalize interest in the game, but his work could not have been done without Marvin Miller (1917 - 2012). Marvin Miller is baseball's unsung hero, credited with unionizing the players and creating a more equitable power balance between players and ownership. He has been described as one of the most importent men in the history of Baseball, and even professional sports as a whole. An introduction to his life and a selection of his career will be explored as well.

Finding and selecting artifacts for this exhibit proved to be a difficult apsect of telling these stories. As did choosing the right part of their stories to tell. However, the content drove this process and led to an exploration of the the legacies of Greenberg and Koufax's public Judaism, and a keen interest into the unionization of professional baseball.