Introduction

Calaveras, or skulls, are commonly used in the holiday known as Dia de los Muertos, The Day of the Dead. Dia de los Muertos is a Mexican holiday in which both life and death are honored with colorful flowers, dresses, decorations, along with a variety of foods and drinks, all in the remembrance of those that have passed. The first two days of November are used for this celebration, and has been used for hundreds of years. In fact, it's actually longer than that. Dia de los Muertos has been celebrated for 3,000 years. It predates to Mesoamerica, when the Aztecs still had a living community. The difference is, this lasted about one month rather than the two, sometimes four days that modern Day of the Dead celebrations last. Just like then, the Aztecs would create altars and craft decorative skulls to honor their dead. It was, and still is, a celebration of the cycle of life.

It's a unique outlook on death that not many cultures around the globe can relate to. There's the Japanese Obon Festival celebrated on August 15th that has three days of dancing, games, and fireworks. Nepal has the Gaijatra, going on for eight days in either August or September, where they lead a cow through the streets to symbolize leading the dead to the after life.The Quingming Festival in China dates back to 732 AD, where families come together to clean their ancestors tombs to honor their spirits. Lastly, Korea observes Chuseok, a dual celebration of their harvest festival while also creating food and other crafts to honor their ancestors. There are many other nations that have similar festivals to honor the dead, such as Bali, Cambodia, and Malaysia. However, Mexico's Dia de los Muertos is special for it's long origin, and the ideology that surrounds it.

One such piece of history is a man named Jose Guadalupe Posada. Born in 1852 in Aguascalientes, Mexico, Posada would grow up to become a lithographer and engraver and become prominent by his use of calveras in his art. A majority of the objects in this exhibit are created by Posada, and that's because of the impact he made on the prominence of calaveras in Mexican culture. His most recognized artwork is that of La Catrina, a female skeleton wearing a large, ostentanious hat, sporting a wide grin that's equally chilling and jolly. That doesn't mean Posada's other pieces are to be overlooked. Posada made thousands of pieces of art, and many of those include the use of skeletons and skulls. Most notably, these works have the skeletons acting like they are still alive. This includes doing everyday jobs, to singing, dancing, drinking, crying, cheering-so many emotions on bones that we typically only see on humans with muscles and skin. Posada's work wasn't strictly cartoonish skeletons. He had experience in politcal cartoon work too. These works scorned people who shied away from their Mexican heritage, mocking those who tried to appear European. His push to accept and appreciate Mexican culture garnered him the title of "printmaker of the Mexican people." This was also because his work could be accessed by the lower class people of Mexico.

Posada's work, ties together what I want to come out of this exhibit; to show the audience Mexico's ideology of life and death, that death is not a thing to just mourn but to honor the life that was lost and celebrate the memories that was made in that life. The use of calaveras in Dia de los Muertos is but the most projected instance where calaveras are shown. Posada's artwork are but small fragments that propagated the use of skeletons and skulls in modern Mexican culture. It helped the people embrace their past and caused a resurgence in their history that gave them something to be pround of. Something unique to their culture that they can celebrate.

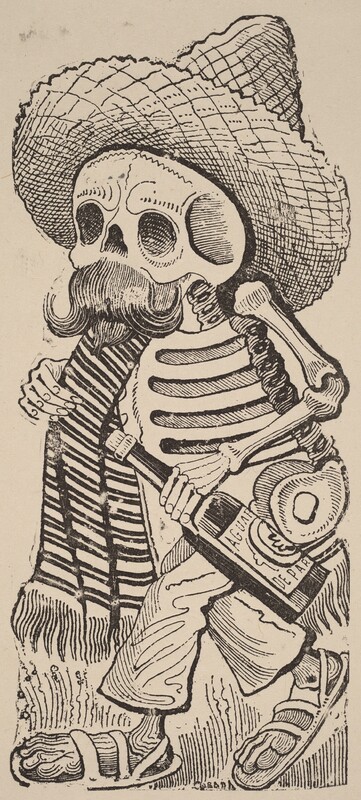

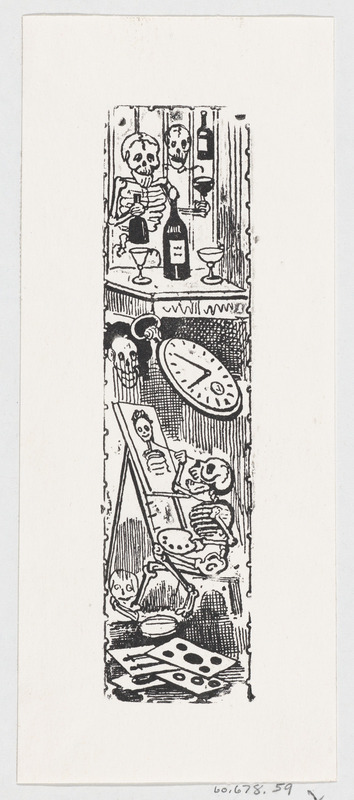

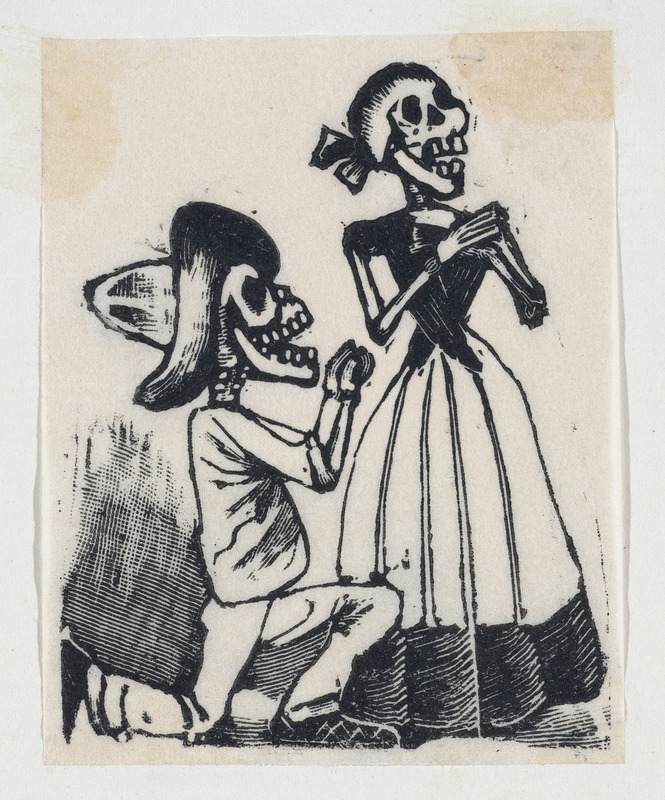

The objects on this page are relief etchings made of zinc created by Jose Guadalupe Posada. All were made at different times in his life but are all crafted with similar engravings that are distinctly Posada's work. Primarily and black and white (due to the type of art medium) these works are but a smidgen of what Posada's artwork emboldens about Mexican culture's ideology on calaveras, as far back as the mid 19th century. With how popular they became with the lower class of Mexico, it's safe to say that the use of skeletons and skulls in this manner of living is a key factor in Mexico's culture. Some might argue that Posada's more critical work on elitist figures corrupts this view, but that's the point. His artwork that criticizes elitist and political figures at this time in Mexico were only about those that frowned upon Mexican culture and tried to reject their heritage for foreign cultures-mainly European countries attempting to take control of Mexico's political/government for their own gain.

Each of these works crafts the subtle protest of the erasure of Mexican culture. The heritage that each Mexican person has, no matter what class they may be in. The traditions that span generations, that go back centuries. There's also the impact of what the skeletons do that paint the simple but beautiful picture of life in Mexico. The Mustached skeleton on the left wears what's typical dress wear for a man in Mexico at the time, if not a little exaggerated, and he holds a bottle in his hand. The work on the right side of the page has two skeletons, both casually living their lives with the one on top tending a bar while the one below it lounges and paints what he wishes. Lastly, the image at the very bottom has a couple, man and woman, captured in a moment of assumed distressed passion that can be seen in the daily life of any first young lovers.

These works aren't just cartoonish skeletons acting for the audience's amusement. They are living the lives that they had before they lost them. Casual instances of taking a stroll, working, creating art, and dealing with emotions such as love. It's actions that any human being can relate to, whether lower or upper class can comprehend. And because it is so ingrained in Mexican culture, the use of calaveras, these images aren't out of the ordinary. They don't see an ominous being of bones mimicking human nature. You see a life reliving its memories and accepting their fate. The cycle keeps turning, and in Mexican culture that isn't something to shy away from, but embrace as part of them

Curatorial Statement

As I mentioned before, my goal is that by the time the audience has finished viewing this exhibit they will have understood the viewpoint of life and death that Mexican culture has. The idea is to inform the audience about the importance of Dia de los Muertos, but most importantly the history and symbolic significance behind the use of the many colorful skulls that majority of us see during late October/early November. I hope to show that the use of calaveras spans generations, and is part of the ancient tradition of Mexico that spans back to the Mesoamerican times. A connection of life and death, an alternate view of what we naturally see as taboo in most cultures. It will show the history of use, and will explain to viewers how Mexican culture does not see skulls as merely a symbol of death, but a connection between life and death that isn’t to be shied away from.

After going through this exhibit, people will have both a better understanding about Mexican culture and their point of view on life and death.This exhibit is designed in a way that even those with minimal knowledge on Mexican culture will be able to easily understand this concept. I hope that they take from this experience the curiosity and ease to broaden their horizons on different cultures. To seek out more knowledge about other foreign cultures that before they brushed off or abandoned due to embarrassment or lack of resources. I would like to think of this exhibit as an introduction to Mexican culture. By using a well known holiday such as Dia de los Muertos I am able to already relate a common connection that the majority of people have and develop that connection into something deeper than just a holiday. This exhibit uses images prominently created by Jose Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican artist, and other artifacts that are easy for a person to understand.

By having simple imagery/items it will encourage the viewers to go through the exhibit to see what more they can see, and in turn read what they are about/represent. The artwork themselves all involve skeletons and skulls. A lot of them are created by the same artist, but nevertheless connect in a way that is unique to the culture the exhibit focuses on. The cartoonish, almost satirical imagery that the artwork holds adds to the idea of the altered view that Mexican culture has a skull/skeleton, and therefore life and death. The connection that these objects have, is that they all represent the lives that were once led before death, and are proof that calavera prominence in Mexican culture hold a deeper meaning than funny skeleton pictures. While a life is over, that doesn't mean that's the end. The person's memory will only cease to exist once there is no one to uphold it. They may not be livng but their life isn't completely over. After all, death is but a part of the circle of life. There is no need to forever mourn death as it is natural. You don't need to see it as a strictly somber thing. It doesn't have to be a taboo. Mexico's unique outlook on life and death is a topic that is either glossed over or ignored. I hope these objects will help show that Mexico's view of life and death as an honored duo will reign.

Author and curator for this exhibit is Akira Castillo.