Artwork Variations

Much like the traditions that were originally conducted, the art that is used in Dia de los Muertos has changed. While not on the same ritualistic (or sacrificial) aspect that Dia de los Muertos had when the Aztecs celebrated, honoring those that have passed is very much present. The shift of focus from a ritual to a tradition can be traced back to European influence once they began colonizing the Mesoamericas. Religious influence, mainly Christianity and Catholicism, would target any faith-based actions once they became aware of its presence. Seeing the foreign practice would encourage the colonizers to coerce natives to abandon the majority of their rituals.

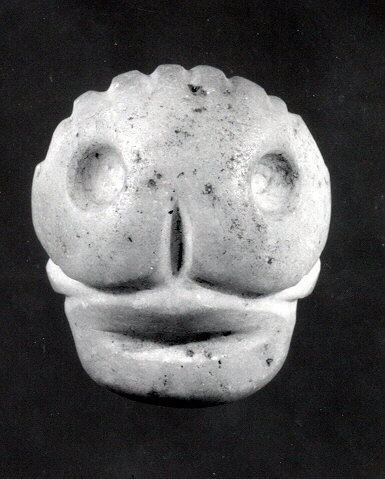

The Aztec tradition of human sacrifice to their gods was real. Archeological evidence can be found of both ceremonial tools used in the rituals as well as constructions they created to go through with their sacrifices. Honoring the dead is in the same boat. Both of these acts involved the use of human skulls. Whether it was real skulls or artistic creations of skulls ) pictured above, the amount of skulls that were used in their culture was disturbing to outsiders. Unable to wrap their head around the connection of life and death, nor the continuation of reverence to the dead, and the belief that spirits returned yearly to simply visit the living, Mesoamerican traditions were rejected. To not only revere skulls but to have them be a part of a symbolic significance within their culture, it was frowned upon. Death was already a taboo subject, but this took the cake

However, as decades went by the use of skulls within Mexican culture never faltered. Artwork such as the one to the right was found in the 16th century. It's especially interesting because it includes the use of a cross, undoubtedly the influence of Spanish Catholicism.The fact that the cross was incorporated into the traditional mesoamerican use of skulls shows the cultural blend that occurred during this time period. And looking at the modern age Dia de los Muertos, Mexican culture in general really, you can see that this blend only continued to evolve.

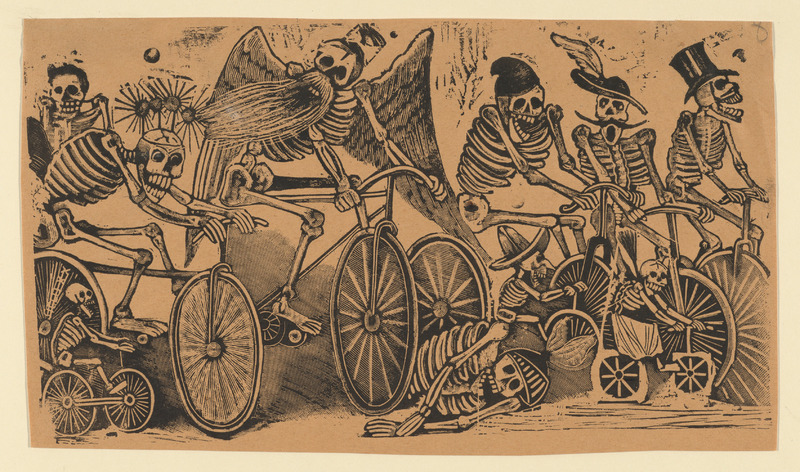

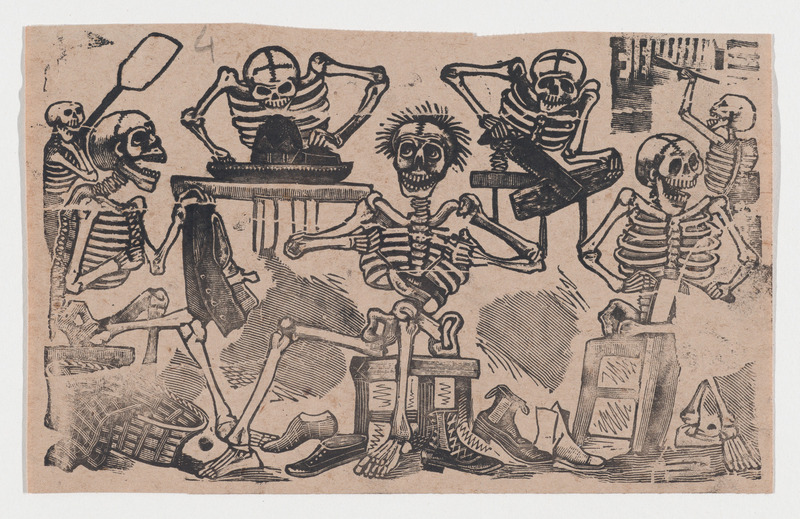

In the 19th-20th century, Jose Guadalupe came out with a series of artworks of calaveras and skulls that revolutionized the sugar skulls that we know and love today for Dia de los Muertos. His work empowered those of Mexican descent to take up his artwork and embrace their heritage in a way that was unique to them. Modern interpretations of Posada's work are much more colorful, but nonetheless they still hold the key idea of skeletons and skulls holding importance in Mexican culture.

Each of the objects on this page share, of course, the imagery of a skeleton or skull. The top left object is the earliest, and was made in the range of dates when the Aztecs were still active, around the 14th to early 16th century. The Aztecs migrated to central Mexico around the 14th century. This carving was found in Mexico, Mesoamerica, and due to the similar dates is presumed to be of Aztec origin. Thus, it implies the use of skulls within said culture. My inspection of the stone concludes that it's not maliciously carved, and even looks like it's smiling. This basic carving was probably a gift, and given the lack of animosity in its details you can say it was a common thing for the Aztecs to make.

The rosary on the top right holds some sort of religious connotation, given the cross that's below the skull. Interestingly enough the skull bears a crown. The source of origin for this crafted item is most likely Mexico. In the 16th century the Spanish brought Roman Catholicism to Mexico, and the period that this was crafted in lands in the same century. Nevertheless this object, despite foreign influence, still holds Aztec/Mexican rituals. The use of a skull along with a religious symbol is typically a bad thing, an omen. But rosaries are an important object within Mexican culture. They help a user keep track of their prayers, and signify a deep relation to the Catholic Church and God. The fact that this individual included a skull within their rosary goes to show that no matter the changes that may come from powerful outsiders the past will always be remembered and embraced by the people of Mexico.

The last two objects on this page are both created by Jose Guadalupe Posada. Both of them are wild, vibrant, full of life that are conducted by none other than groups of skeletons. The skeletons in both images are wearing wide grins, some with their mouths open, shouting with excitement and joy. But skeletons are dead, they do not have muscles or skin to depict happiness or exhilaration. Somehow, Posada makes it work. Just as the Aztec carving, and just as the symbolism of the rosary. They all come together to symbolize the positive light in which calaveras are seen and used in Mexican culture. Spanning centuries, calaveras have managed to stay a part of Mexican culture. Even after the people changed their name and after an elitist dictator attempted to force foreign influence into their lives, the Mexican people remembered their past, rallied behind their heritage, and continued to embrace their culture in a way they always did. Life and death, death and life. A natural cycle to be celebrated and honored, using calaveras all the while