Origins of Dia De Los Muertos

The origin of Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, starts with Mexico. It is a Mexican tradition that has existed for generations. Observed on November 1st and 2nd, Dia de los Muertos are days where families come together to remember the people that have passed. The celebration includes a clash of skeletons and vibrant colors displayed as flowers, baked goods, and colorful decorations. The calavera, or sugar skull, is the key figure of Dia de los Muertos. Adults and children alike don colorful skulls, crafted with paints, paper, feathers, on their own bodies and as decorations to their surroundings. One such item is called an Ofrenda. Ofrendas are altar-like constructions that are decorated with bright, colorful paper, flowers, pictures of passed loved ones, and the deceased favorite foods, drinks, even items from when they were still alive.

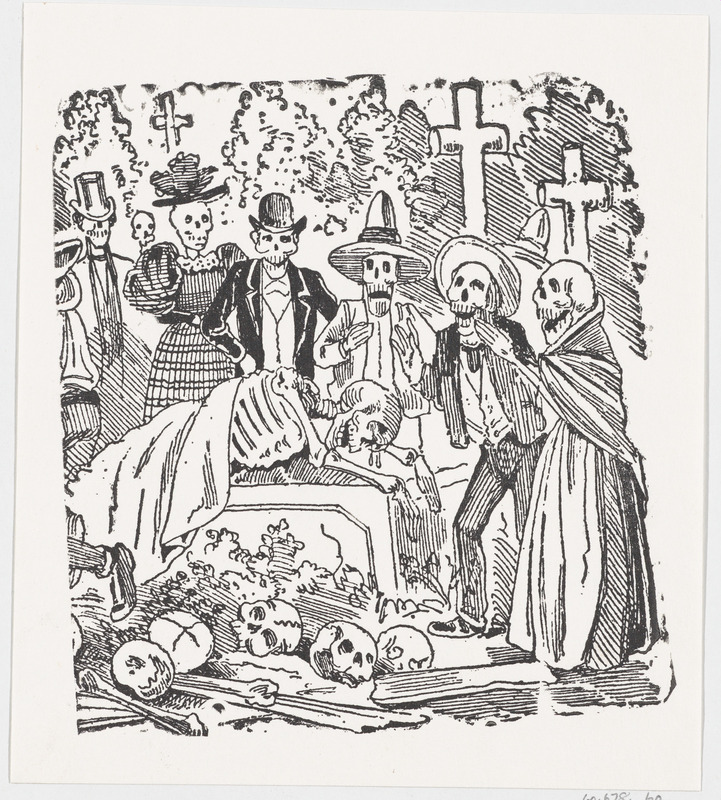

The use of calaveras within Mexican culture dates back to before Mexicans called themselves Mexicans. Back 3,000 years ago the Aztecs used skulls in a range of rituals in Mesoamerica. This ranged from sacrifices to their gods to ritualistic ceremonies that involved the burials of their people. They too celebrated death, but it lasted a month rather than at most a week in modern times. Altars were crafted and decorated with things such as a variety of food, handcrafted goods, clothing, tools, anything that was of significance to those that had died. It was believed that during this time their spirits would be the strongest, and so in order to welcome them and eventually guide them to the afterlife, these rituals were conducted.

That wasn't the only thing they did though. Something that I sadly couldn't add due to copyright was this rather morbid construction that I found detailed in a text that was researching Aztec rituals, and a similar work made in the modern times. It starts with two stakes in the ground, with many poles connecting the stakes horizontally. On these poles were skulls, some decorated some not. In Aztec times these were real skulls. The one I found more recently was of course fake ones, but the similarity between the two images couldn't be mistaken. About 3,000 years later and this construction was still being done. The altars as well. We call them ofrendas now, but the tradition of creating these massive grave sites and decorating them with goodies of all kinds resonates from what people have done from so long ago. Altars certainly aren't an uncommon thing. In many cultures altars were, and are constructed for gods, ancestors, a being of higher power or just one to be respected. However Mexican culture is unique in a way that altars are constructed and respected annually, and can be made for even beloved pets that were a part of one's family.

The idea stands that Aztec rituals are reflected in the traditions of modern Dia de los Muertos celebrations. Despite being a tad less morbid, the use of calaveras is still there. Going through the prominent events pointed out in this exhibit, the transformation from the Aztecs real human skull use, to Posada's variety of skeletal remains coming to life, and now the modern age of coloring fake skulls and even dressing up as skeletons to sing, and dance, and play, the use of calaveras can't be more influential in Mexican culture. Whether it is intentional or not, life and death is symbolized by animating skeletons as living beings and acknowledging that where there is life there is death, and where there is death there is life. This easy acceptance is one unique to Mexico's heritage, and one that continues to be a part of it today.

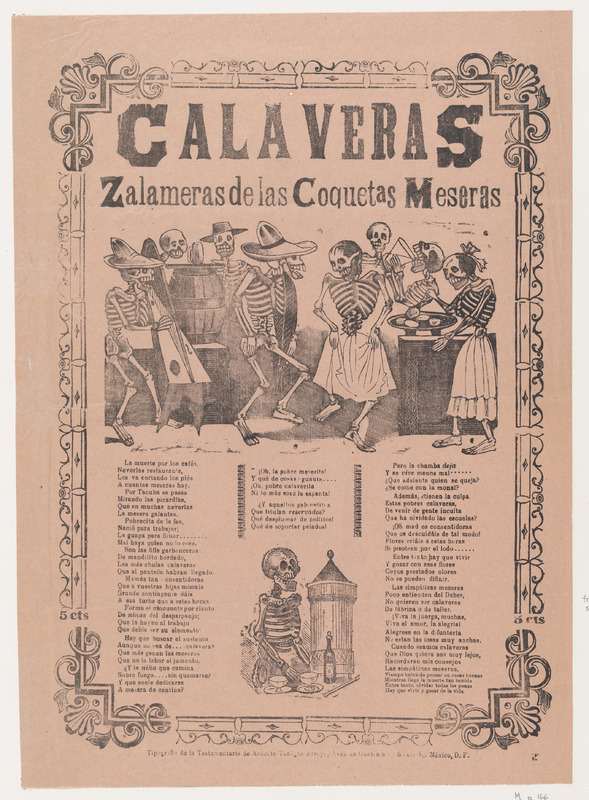

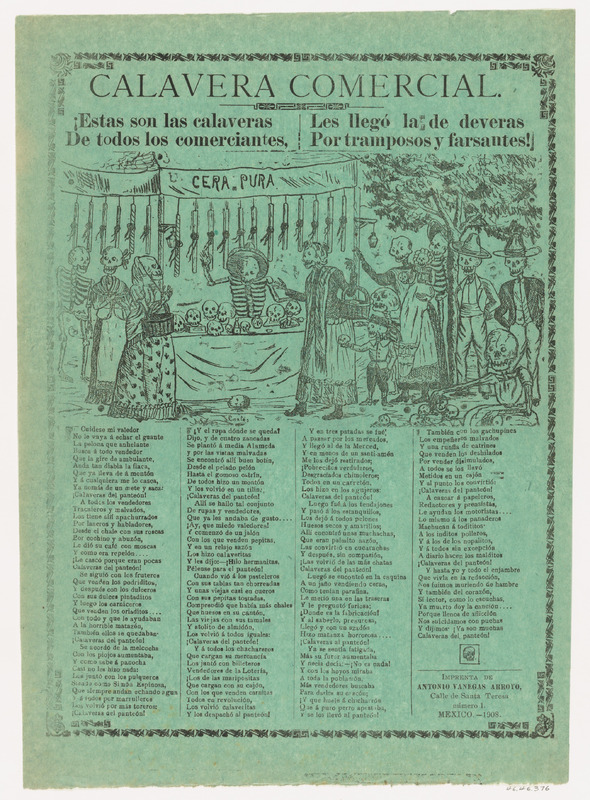

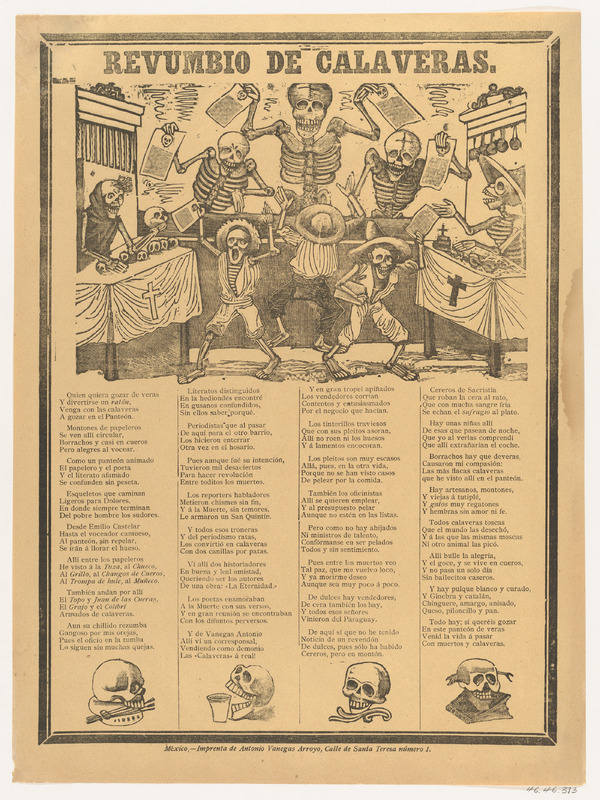

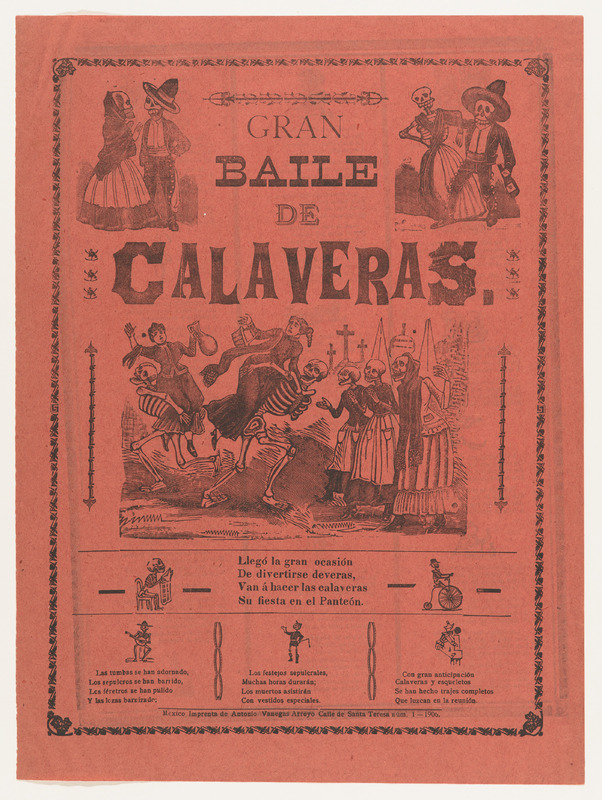

The objects here capture, as foreign influence would put it, the barbaric nature of skeletons in Mexican artwork. Each was made in the late 19th, early 20th century, right before the outburst of the Mexican Revolution and overthrow of Porfirio Diaz. In fact, the artist of many of the objects in this exhibit, and on this page, Jose Guadalupe Posada, famously created pieces that denounced Diaz, whether it was for the unequal distribution of land, poor economy of Mexico, or how Diaz openly rejected Mexican culture and embraced European culture.

All of the pieces on this page, without directly addressing it, celebrates Mexican culture. By using skeletons and skulls, Posada is honoring Mexican culture by incorporating calaveras into these artworks that can be accessed by the general public. It's a way for them to unite under a common tradition and subtly go against the ruling leader's ideology of erasing Mexican culture. This idea of history erasure was headed by Porifirio Diaz, an elitist that favored foreign powers for personal gains.