A Metallic Alter Ego

"'Gazing on him is like running with your eyes fixed on the sun,' the poet continued; the young count, like the sun, “dazzles so that nothing else is visible in between.'" - Newbigin, “The Florentine Honors”

The knights of the Renaissance took part in a form of knighthood different from but deeply inspired by the extravagant and exhibitionistic chivalry of the European Late Middle Ages. Renaissance knights remained members of cavalry as war remained a large part of European life into the Early Modern period, however, knights were increasingly involved in simulated battles referred to as jousting tournaments during which two knights on horseback displayed their martial skills to an on-looking crowd, and ceremonies such as parades which were held on various holy days. This developing realm of largely harmless knightly duties allowed space for the advancement of armor that focused on its theatrical, exaggerated decoration. As the role of Renaissance knights further evolved and involvement in militaristic endeavors decreased, these imporant social roles evolved knighthood into a symbol of status, assigning significant social power to the act of donning armor.

One of the realms of social power highly impacted by armor was the construct of masculinity. The preceding history of knighthood in the Middle Ages which was reserved solely for men formed a cultural understanding of what it meant to be a knight which was heavily connected to manhood. This culture continued into the Renaissance as the sixteenth century perception of masculinity continued to be tightly interwoven with arms and armor. As Timothy McCall describes,

“Renaissance bodies were not mere flesh but social bodies constructed by the clothing and accessories that not only adorned but also constituted and reflected ideals of gender and class.”

This reflection of social ideals reveals a kind of exhibitionistic requirement to the masculinizing effects of armor, relying on the eyes of the broader society, and oftentimes specifically other men, to play the role of audience in the creation of masculine identity. For example, lords and other nobility wore highly ornate armor to cement a visual form to the values of power and authority. In comparison to the plain, earth toned clothing of most Renaissance commoners, the armor of nobility glittered, shone, and clanked while walking or riding on horseback which attracted audiences and announced the body’s high status. The painted portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici standing proudly in armor displays this intentional desire to be seen as an armored man. A prevalent goal of Renaissance portraiture was to capture the highly personal, individual appearance of each subject. This common intention implies the decision to depict Cosimo I in his full suit of armor reflects his physical appearance and identity as one deeply connected to the values of armor.

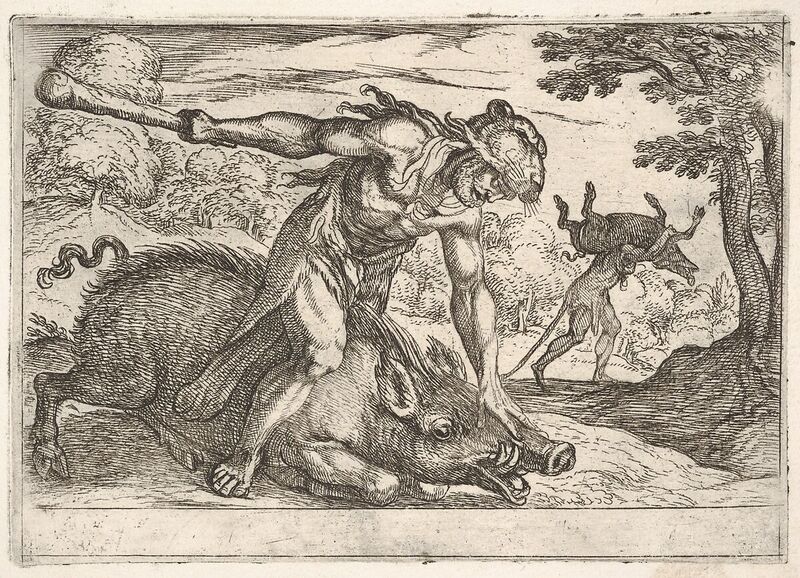

Armor also came to function as a method of molding the wearer’s body to the idealized heroic male form, rejecting the inherent vulnerability of the human body. By the fifteenth century, artistic works all 'antica, which emulated the armor of ancient Greece and Rome, became a standard part of Renaissance visual culture. The earliest example of such armor is an Italian helmet from the late fifteenth century which is formed into the shape of a lion's head. This helmet was likely made to recall the story of the Classical hero Hercules who slayed the Nemean lion and donned its pelt atop his head. In much art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Hercules wears this lion’s head as a helmet and its skin trails behind like a cape to symbolize his strength and courage. For Renaissance princes and condottieri, this fifteenth century lion’s head helmet may have enabled the emulation of these same Herculean virtues.

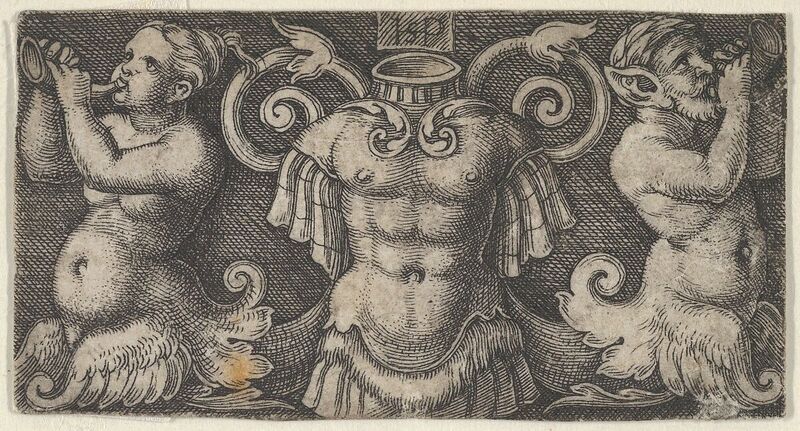

The production of armor for Renaissance parades and pageantry catalyzed the reappearance of armor all’antica which visually harkened back to the powerfully articulated musculature of Greco-Roman thorax armor.

Through the donning of this armor all 'antica the Renaissance man discarded the imperfections of his own body and transformed himself to the culture’s most ideal form of physical proportion and beauty, recalling Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man in its lack of bodily imperfections. The armor of Guiobaldo della Rovere, Duke of Urbino exists as an example of this masculinizing cuirass as its nude, unarmed nature sought to visually deny the protection it offered through emulating an invulnerable, impenetrable body to those who gazed upon it on the inherently vulnerable and penetrable body of its wearer. The significant gilded, intricate decoration of this armor simulteniously communicated a message of power and status. Thus, for Renaissance men, armor all 'antica such as that of Guiobaldo della Rovere and the fifteenth century lions head sallet created a kind of escape from the fears of unmasculine vulnerability and imperfection, becoming a kind of “metallic alter ego.”