Home Is Community

The marginalization of queer people has necessitated the creation of queer-centered spaces. As queer people face discrimination and are barred from predominantly heterosexual and cisgender spaces, many turn to forming spaces of their own, which in turn attract queer patrons who have faced discrimination. Diverse in form and function, queer community spaces are crucial components of maintaining communication and mobilization toward queer movements. They also provide a space of safety and understanding for their patrons. This safety sometimes comes at the cost of obscurity, trading popularity for protection. While it can become harder for community members to learn of these safe spaces, their hidden nature allows them to continue business without threats.

Sylvia Rivera (with Christina Hayworth and Julia Murray) by Luis Carle

The pride parade is perhaps the most widely known queer space. Hosted in both metropolises and small towns, pride parades are simultaneously celebrations of existence and acts of protest against institutional homophobia and transphobia. The first pride parades were held on June 28, 1970, on the one year anniversary of riots against police brutality at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City. Sylvia Rivera, the woman in the center of this image, was a transgender woman present at the Stonewall Riots (and threw the second Molotov cocktail at police officers). An activist for LGBTQ+ rights, the Black Liberation movement, and more, Rivera spent much of her life fighting for her fellow people in New York City. Despite her deep involvement in the movement, she was prevented from speaking at pride parades for many years due to the exclusion of transgender people. She and Marsha P. Johnson, a self-identified drag queen, started the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) around 1971, as well as a STAR House for young trans people to stay while planning protests and receiving support. In this image, Rivera is flanked by Christina Hayworth, the first openly trans woman in Puerto Rico and a member of the Stonewall Riots, and Julia Murray, a trans woman who stayed at the STAR House and became Rivera’s life partner.

Luis Carle, the photographer, is a queer Puerto Rican man who began studying photography in the 1980s and produced much of the documentary queer photography throughout the 80s and 90s.

Michelle, "C'est La Vie" Club, North Hollywood by Anthony Friedkin

Drag bars are another popular community space available to the queer community. Typically centered on performances by drag queens, drag bars may also provide opportunities for queer artists and events that don’t necessarily involve alcohol. Historically, drag queens and the spaces they perform in have been contested as inappropriate, due to the vilification of eroticism and sexuality. While many drag queens do not incorporate sexual content into their performances, those that do still should not be subject to discrimination on the basis of their sexual preferences with consenting adults.

Drag bars are one of the few community spaces that openly explore complex representations of gender. Some drag queens identify as cisgender men who enjoy crossdressing, while others are transgender women and men, nonbinary, or genderfluid. Even at its base level, the inclusion and acceptance of drag in a space broadens its capacity for the inclusion of queer people. Often, these spaces are obscured for the safety of their patrons, employees, and performers. Little is known about Michelle, the subject of this photo, but her presence as a drag queen lends credit to her contributions to queer spaces.

The Prom Queen by Nancy Andrews

Lorelei Holness (right) and Deborah Rowett (left) of New Jersey were twenty-seven and twenty-nine when Holness was crowned the queen of the 1991 Prince William (Virginia) Gay and Lesbian Alliance Prom. The event was created for queer people who could not attend prom with their true romantic partners in high school due to homophobic school districts and peers. In this environment confirmed to be safe, Deborah is able to kiss Lorelei on the cheek, a public display of affection connecting the two as lovers. Proms like this one are common across queer community organizations, though generally in larger cities and metropolitan areas. Through events like this, queer people can realize the dreams of their childhood with their partner by their side.

To learn more about Nancy Andrews, the photographer, visit Home Is My Loved One or Sources and Resources.

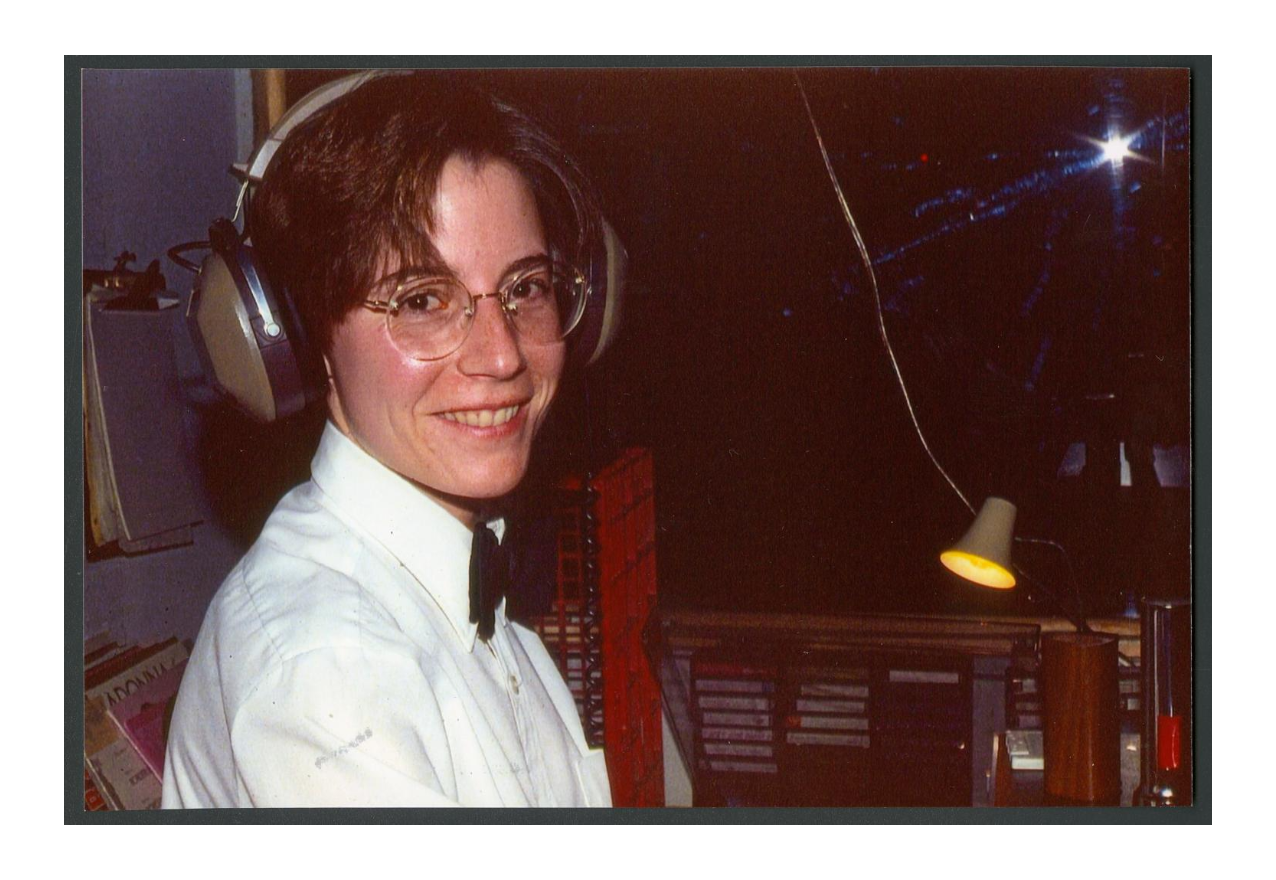

Herizon Bar, scrapbook by Unknown

Herizon Bar, located in Binghamton, New York, was a lesbian club throughout the 1970s and 80s. Staffed entirely by volunteers, Herizon was a space for not only drinking and partying but also a home to a, “rock band, theatre company, restaurant, campout, annual New Year’s cabaret, and Passover seder.” This was a space for queer women, relatively invisible to the straight public and exclusive of men for the safety of queer women who rarely had a place of their own.

In this photo, Claudia S., a frequent DJ at the bar, stands in the mixing booth. This is the first photo included in a scrapbook of photos from the bar’s history, which can be explored further on the Smithsonian website.

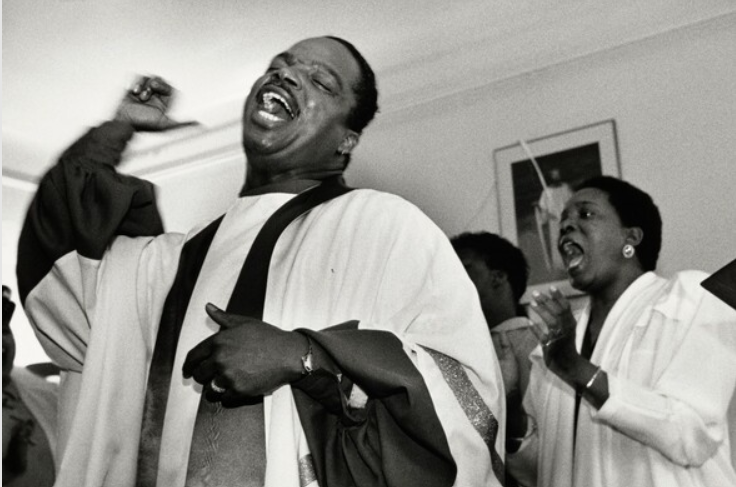

Full Truth Unity Fellowship of Christ Church by Nancy Andrews

The church is one of those community spaces associated with the home in popular culture. However, for many queer people, churches can represent the negative experiences they’ve had with those who preach homophobia in the name of God. The intersections of religion and queer identity can thus be very complex, as individuals must grapple with which interpretation of faith best fits with their self-interpretation.

“In the black community the church is the most powerful institution, and it’s always represented civil rights and social services. I felt like there was a need for those kinds of services in the black gay and lesbian community.” – Renee McCoy, founding pastor of the Full Truth Unity Fellowship of Christ Church in Detroit

Renee (right) filled that gap for a Black and queer religious community by founding the church, and created a space where queer people could feel confident in both their faith and identity. Allen Spencer (left) was one such person, a Black gay man who became the assistant pastor and minister of music for the church and found it revolutionary to hear his sexuality be supported and uplifted by a religious community.