Nationalism and Independence

Religious leaders did not see the Virgin Mary’s apocalyptic appearance as showing that the end times were coming but that it marked the creation of a new world which would be Mexico. This theory of Guadalupe being the woman of the apocalypse led the way to the Nationalist idea that emerged during the mid-1700s that Mexico was a biblical chosen land. To help further support this idea it aligned the origin of Mexico as told by the Spainards with the Biblical story of the desert of Sinai and the land of milk of honey. Emerging nationalists thought that Mexico being a chosen land meant that they deserved independence from the Spanish crown.

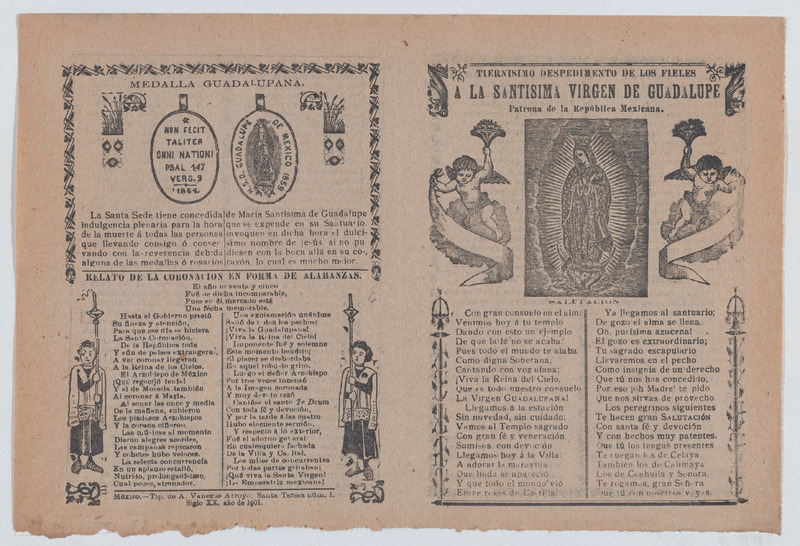

This strong connection between the Mexican people and Our Lady of Guadalupe was further solidified in 1737 during an epidemic that struck Mexico. Within 8 months the disease had taken over 40,000 lives in Mexico City alone. The church encouraged people to start praying to Our Lady of Guadalupe to help alleviate the disease. It was said that after the Virgin Mary had been invoked that the deaths quickly came to a halt which allowed her to be made an emblem of the Mexican people. This understanding was further put into place when a book by Cayetano Cabrera y Quintero (1698-1775), a representative of the archbishop, compared Mexico to a second Rome. This further laid the groundwork for the foundation of the country to gain independence due to its religious importance. It is to be noted that the main groups that pushed her importance were people of Spanish descent and upper class standing.

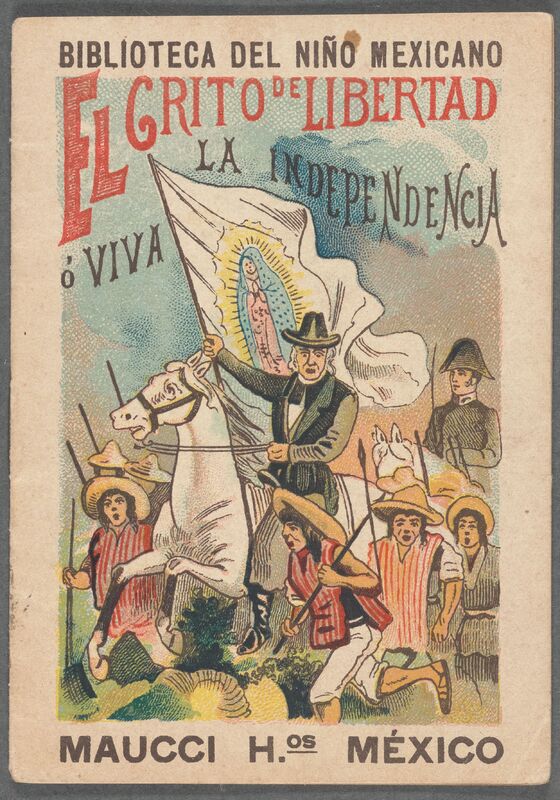

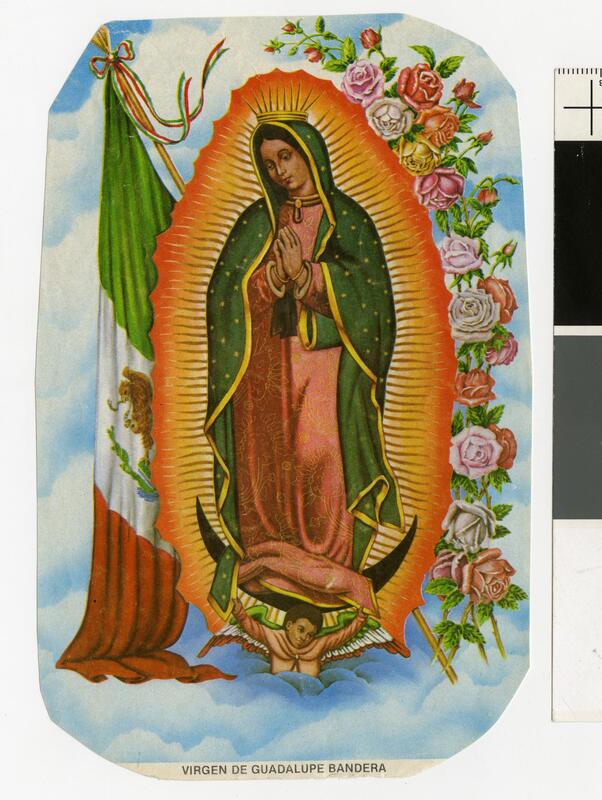

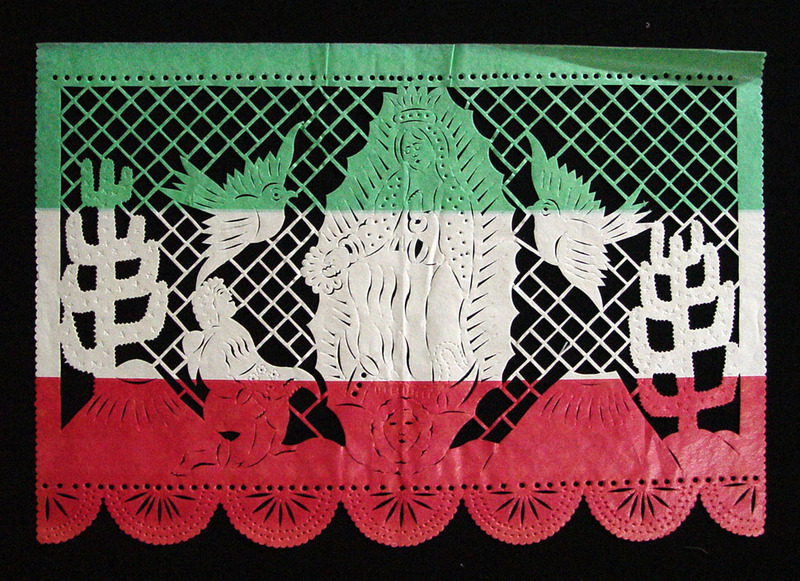

This belief that Guadalupe had picked Mexico as her new chosen land became central to the fight for Independence from Spain The first Mexican battle flag boasted the image of the Our Lady of Guadalupe. With the initial leader of the first revolution, Father Miguel Hidalgo (1753-1811), titling her as the “General Captain '' and parading the flag through villages. She was said to have protected the Mexican people in the past therefore would watch over them as they fought to become independent. After Father Hidalgo’s death his successor, Father José Maria Morelos, (1765-1815), required all of his supporters to wear the emblem of Guadalupe further ingraining her in the war effort. In 1828 Father Hidalgo was officially recognized as a hero with his name being placed in the cult center at Tepeyac which inspired the first president to adopt the title Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The ties between religion and nationalism only continued to grow into the 20th century. This was most clearly demonstrated in 1910 with both Pancho Villa (1878- 1923) and Emilio Zapata (1879-1919) using images of Our Lady of Guadalupe in their campaigns. Along with Ceaser Chavez (1927- 1923) using her likeness during the farmworker strikes of the 1960s. However, also during the 20th century Mexico officially declared a separation of church and state which pushed Guadalupe into the realm of popular culture. No longer was she seen as only a religious figure but as a figure of communal solidarity. Her representations in widespread art made her a distinct symbol of Mexican culture and experience.