Drawings and Paintings

While some people feel the need to keep their hands busy through constructing various things, other artistic pieces came from those who alternatively felt compelled to draw or paint. Simply another way of expression, ink or paint on paper is a related form of distracting oneself, especially in adverse conditions, or expressing feelings that may arise while facing said conditions. Many individuals who were interned at camps created through this medium, some being established artists and others being civilians. Regardless of their background or their ability, the goal was universal: depict one's time within their respective camp and to provide a means of seeking solace or distraction for their mind that was potentially plagued by illness.

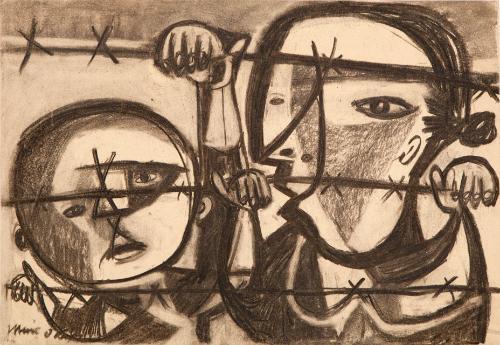

Miné Okubo is an interesting example of the aforementioned group of people who were prior artists and simply kept creating art while interned. She created hundreds of works during her time in both the Tanforan and later Topaz relocation camps, which she showcased and explained in her famous book Citizen 13660. Okubo depicted life in internment a bit differently than her other more hopeful and light works, as seen by her drawings being made with darker charcoal and the imagery being more bleak. The internment pieces, as seen here as well as earlier in the exhibit, depict scenes of loss and imprisonment. Here we see two children looking with forlorn expressions and pain in their eyes while reaching behind barbed wire, illustrating the reality for so many. These sentiments are a theme all throughout the collection of works from internment camps, with some being people crowded together in small spaces or figures of authority barking orders. The expressions on the faces of her subjects and the scenes they are apart of, accompanied by the shading of the charcoal marks an unmistakable air of despair and loss that was so universally felt by all those affected.

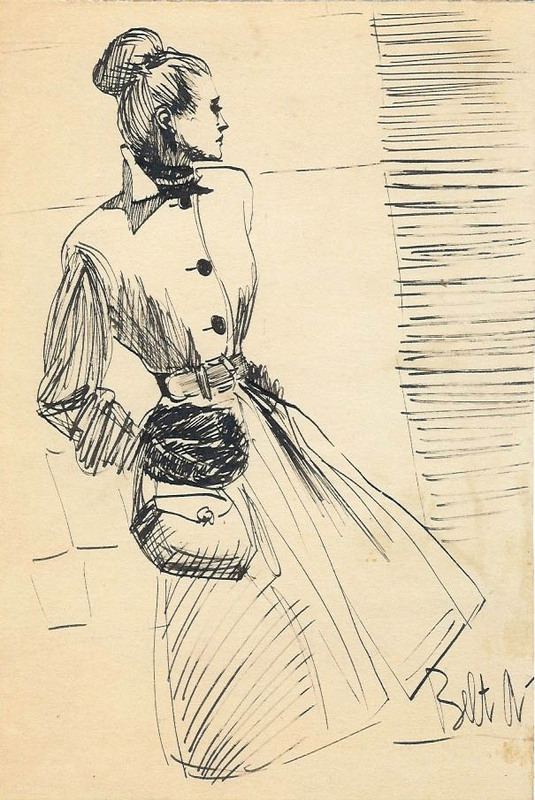

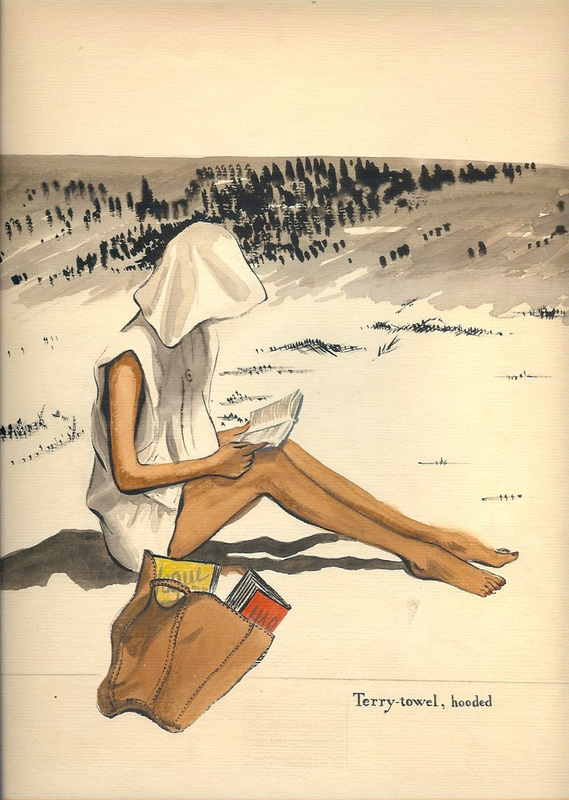

In conjunction with the idea that many who created art simply sought to regain a sense of normalcy after their life was upturned, the drawings done by Doris Ota Saito prove that it may be reached through drawing too. While interned at the Heart Mountain camp, Saito made several “fashion prints” of models wearing potential fashion designs. Saito was likely influenced by and interested in fashion previously in her life before being relocated and interned. This aspect of her past life manifested into a more positive means of distraction as seen in what she produced in her new situation. Both the drawings to the right and left are representations of an outlet in which Okubo could escape her unfavorable situation and remind herself of what she was previously passionate about. The prints are of her very own designs, and it can be seen in “Terry-towel, hooded (c.1942-1945)” that she had new, unique ideas for the time. Such drawings reveal that some instances of creativity are useful means of escaping the harsh reality and aiding in providing normalcy or positivity.

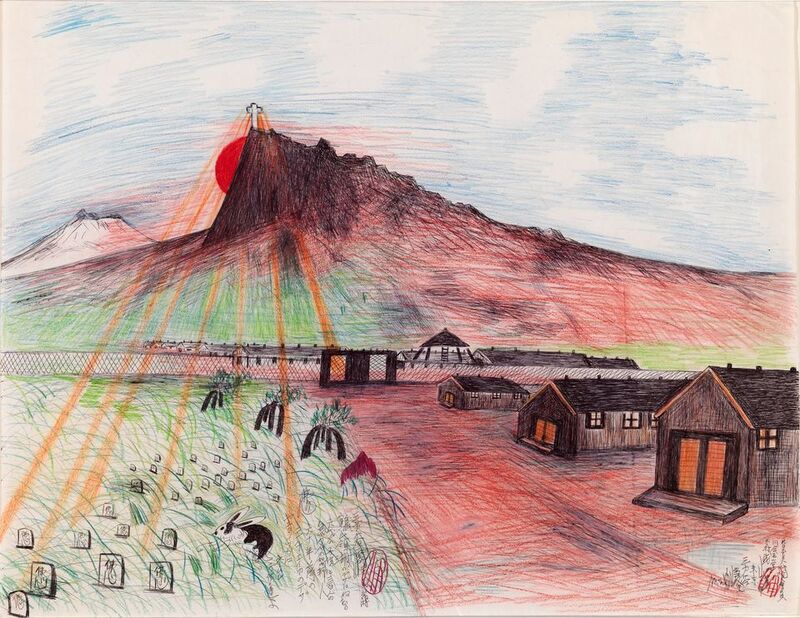

Tying into the physical objects that were created in order to serve in ceremonies because of cultural practices, the emphasis on such cultural facets may be seen in works such as “Cemetery (2002)” by Jimmy Tsutomu Mirikitani. Mirikitani was another established artist who was a victim of the war, famous for his bold style and creation of pieces that were a part of the 2006 documentary “The Cats of Mirikitani”. Here, Mirikitani paints the cemetery of the Tule Lake internment camp in his signature colorful style, yet the subject matter is completely different from his other works. Typically, he depicted pleasant images such as cats or other animals, but here he is reminded of his time at the Tule Lake camp. He drew what appears to be the housing quarters in the bottom right hand corner, positioned across from gravestones in the cemetery, both of which are in front of a fence, watchtower, and a mountain with a cross atop it. Here, both themes of religion and despair may be interpreted.

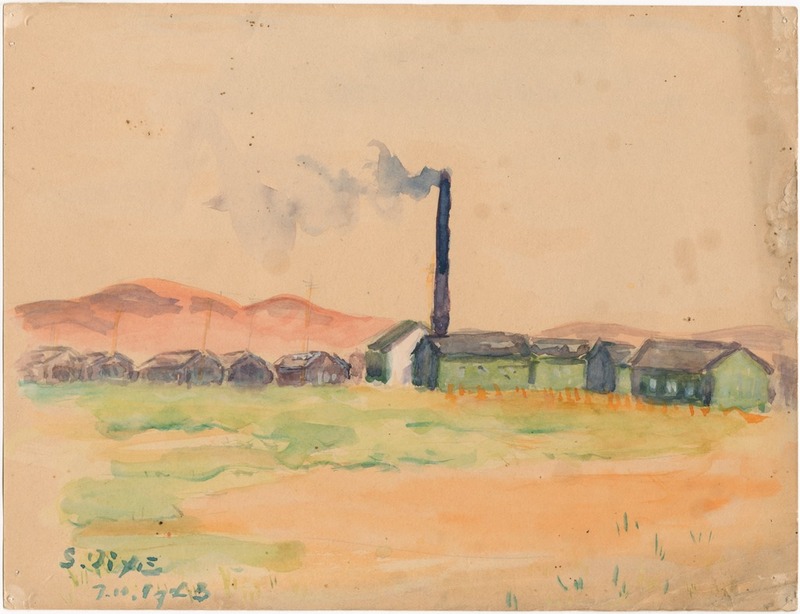

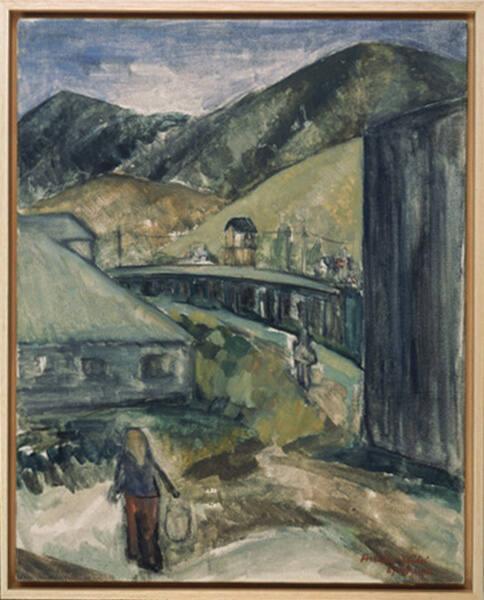

In a more neutral sense, some paintings that were created were simply of the surrounding landscape and void of theme or positionality. It is not to say that the artist did not intend for there to be a voice within the painting, they are only seemingly neutral on the surface. Seen here to the left, Shigenori Oiye is using colorful watercolor paint to depict the landscape of the Tule Lake camp. He illustrates the surrounding buildings in the foreground and the geographical features, like the mountains, in the background. Here, it is hard to gather whether or not he intended to share a particular message or to evoke a certain emotion, but the fact that he was painting life around him said enough. It shows that he was remaining aware of all that he was living through and at the very least, documenting its features. Furthermore, “Barrack 9, Apt. 6, San Bruno, CA (1942) by Hisako Hibi is another example of both a renowned artist who became interned as well as one who created landscape paintings of their camp. Similar to Miné Okubo, Hibi was also intended at both the Tanforan and later Topaz camps, and had a collection of paintings from the time. Many of these paintings in the collection are simplistic in the sense that they simply depict the landscape or minor figures, not including any particularly recognizable emotion. He chooses to use a darker pallet of similar greens and blues, while pointedly focusing on buildings and scenery. This further shows how painting was an outlet in many different senses, sometimes being to mark or remember the features of their surroundings.