Isamu Noguchi

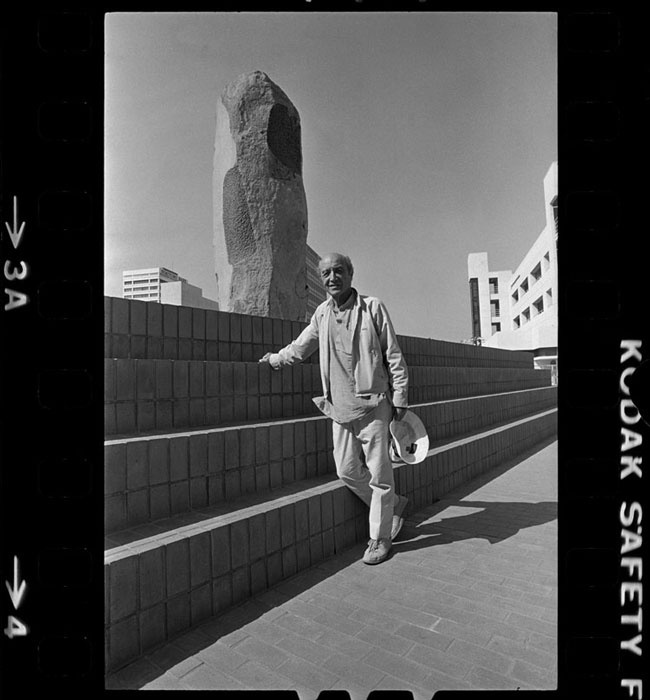

Isamu Noguchi was one of the most influential and widely credited sculpturists of the twentieth century for his unique designs and interesting ways of interpreting life through his work. Noguchi often artistically depicted his experiences living as a Japanese American, as he was born in Los Angeles in 1904 to his Irish mother and Japanese father. After living in Japan until the age of thirteen, Noguchi attended highschool then university at Columbia where he fell in love with sculpting. Thereafter, he spent his days supporting himself through his work and traveling, wherein he was perpetually inspired by different cultures’ art. Having worked in studios in Paris, Japan, and New York, Noguchi always seemed drawn to New York in which he eventually passed.

During his time in New York, the war began to directly affect Noguchi when he began founding the Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy which sought to defend and protect Japanese Americans during the strife and fear mongering of the period. In conjunction with his activism, Noguchi accepted a proposal to teach classes and aid in architectural projects for a camp in Poston, Arizona from John Collier, the head of the American Indian Service. To provide context, Poston was situated on land belonging to the native peoples of the Colorado River such as the Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi, and Navajo tribes. This fact led to strife amongst the War Relocation Authority branch of the US Army and the American Indian Service. Therefore, John Collier struck up an agreement with the WRA to ensure the worthy usage of native land. To do this, he asked that the WRA allow him to utilize the land for his utopian vision because he “saw an opportunity to put into practice an ideal cooperative community” (Knopf, 70).

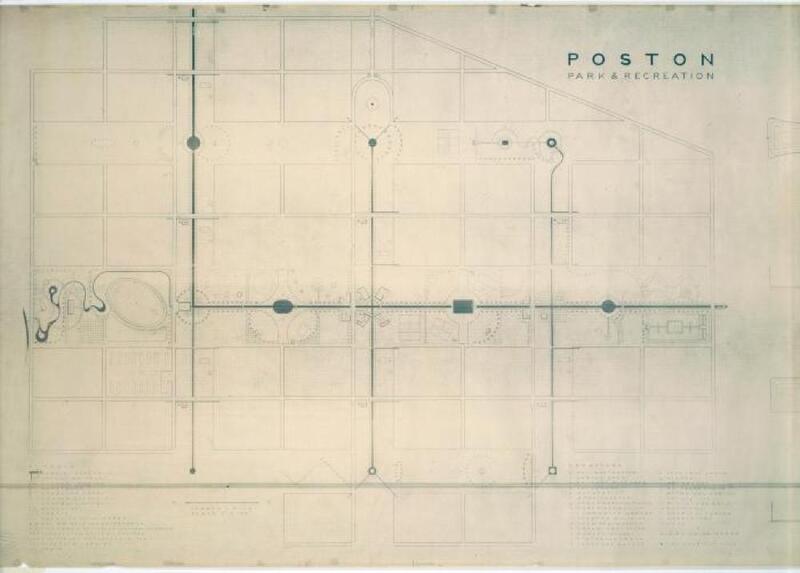

In order to reach this utopian vision, Collier enlisted the help of Noguchi, because he hoped that Noguchi would be able to visit and transform the camp from a cruel institution to a creative epicenter through art classes and “plans for park and recreation areas and to organize activities” (Knopf, 70). Noguchi, having been born in America to a first-generation Japanese American father and being a member of the nisei writers and artists mobilization for democracy, felt a personal call to help in this cause and agreed to come to the camp even though he was virtually unaffected by Executive Order 9066 due to him residing in New York.

While interned at Poston, Noguchi was tasked with creating parks, places for recreational activities for the fellow interned victims, and designing the cemetery. He also sought to aid the internees by teaching art classes with emphasis on pottery and woodwork. However, The internment camp located in Poston, Arizona was way worse than he had anticipated. It was a massive center located in the unforgiving Arizona desert and in just the first year alone, there were 18,000 evacuees suffering in the scorching heat. Noguchi instantly hated staying there and wanted to leave, as he experienced internment in the fullest sense, even stating that life in Poston “must be one of the earth’s cruelest spots” (Knopf, 71).

Unfortunately, the WRA never truly had any intention of upholding their side of the deal and subsequently denied Noguchi his freedom. Therefore Noguchi, who had entered the camp under the impression that he was safe and solely present to teach art and design buildings, became a victim within the concentration camp for over seven months until finally being released back to New York.

Noguchi’s time spent within the camp was grueling and unforgiving, as the Poston internment camp proved to not be far from the utopian vision that Collier had. His traumatic experiences and subsequent negative emotions inspired later art of his. In some of these future pieces, he would occasionally implement materials that were very similar to those found in the desert around the center. The landscape of Arizona also remained in his mind and visually inspired various works such as Double Red Mountain (1969). This piece served as a means of interpreting the “isolating” landscape of the Arizona camp, further represented by the likeness of Persian Travertine to the desert. Noguchi further explains that Double Red Mountain (1969) is a piece that falls into a category that “...are landscapes really, a sculpture of the whole, not an assemblage of parts or props, as with the theater.” (Noguchi, 1970).

This forced internment naturally led to many mixed feelings such as loss and imprisonment, which can be very complex to represent. Such sentiments can be seen in another piece that came from Noguchi’s internment at Poston, My Arizona (1943). Noguchi attempted to express not only the landscape of the camp but the complex, isolating feelings. My Arizona (1943) is a sculpture that is split into four quadrants: the top left with a sheet of pinkish red fiberglass atop a hill, the top right with another hill but with a large gaping hole in the top of it, the bottom left with another hill but with a stick erected atop it, and the bottom right with a simple pyramid shape. Interestingly, when light is shown on the piece, a pinkish red light seeps through from the top left and onto the rest of the sculpture. This illustrates the harsh, hot sun that would unceasingly sine onto the arid and unforgiving desert landscape of the camp. Noguchi himself described My Arizona (1943) as “A recollection of seven months in an Arizona desert camp for Japanese-Americans at Poston near the Colorado River, where the hot sun shines interminably.” (Noguchi, 1943).