Curatorial Statement

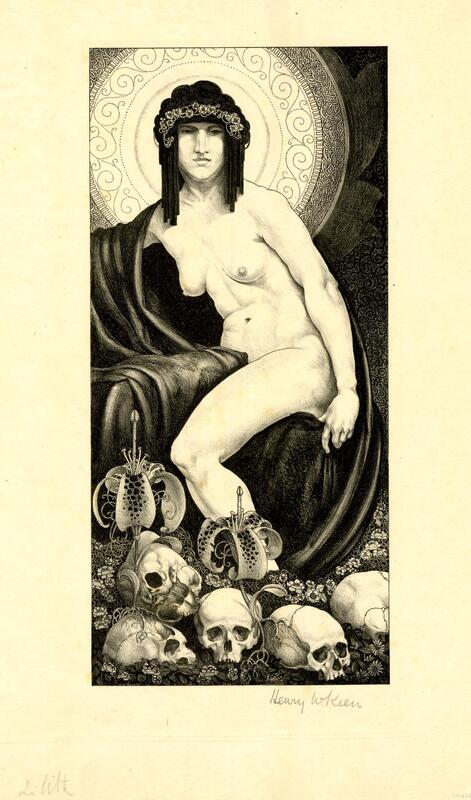

My primary goal with this exhibit was to shed light on the importance of feminist thought by illustrating the historical trend of portraying female power, agency, and sexuality–the same attributes men are generally revered for–as inherently bad and insubordinate. I chose to use Lilith as a symbol for this because of her extremely diverse evolution and varying depictions, as well as her modern transformation into a feminist icon. Lilith perfectly represents the modern movements focused on shifting society away from double standards and the vilification of female independence and women in positions of power. I was personally inspired by the Jewish feminists who have been working to clear Lilith’s name of any wrongdoing since the 1970s, such as Susan Weidman Schneider, who created “Lilith Magazine” and Judith Plaskow, who wrote her own midrash on Lilith free from patriarchal bias (Shapiro 69-70). This exhibit was also meant to illustrate the damage certain misogynistic doctrines (particularly those of the Abrahamic religions) did to the complex female deities of prehistoric (and some pre-modern) belief systems, and real women by extension. I found it odd that even some modern spiritual communities continue to divide femininity and womanhood into two archetypes. All people are complicated, so why aren’t women allowed to be? Why do they have to be categorized? I sought to answer these questions in my research and I tried to structure my exhibit in a way that would prompt the same questions in the readers’ minds. Still, I had some issues in the organization of this exhibit because I originally wanted the project to focus solely on the linear evolution of the way Lilith has been depicted. This proved to be nearly impossible, as Lilith has evolved, devolved, and gone through phases of changing into something radically new only to return to an older state in a matter of centuries or upon reaching a new geographic location. To combat this problem as best I could, I decided to begin with Jewish depictions and the well-known story of Adam’s first wife. I also wanted to discuss Lilith’s modern impact on second wave feminism and neopaganism, but I struggled to find objects to represent that due to copyright claims. The Victorian paintings and artworks were simple to categorize, but the other sections underwent several drafts. I ultimately decided to group the Jewish adaptations together based on the forms Lilith took in the Babylonian Talmud, the Great Isaiah Scroll, the Kabbalah, and Christian ideology (i.e. “Succubus and Mother of Demons” and “Witch and the Snake”). I then grouped the “Dark Feminine Archetype” section with the “Mesopotamian Origins” page to best exemplify the fracture of female divinity and introduce Ishtar and Lamashtu (who were direct Mesopotamian predecessors of Lilith) together before Kali Ma.

-Shaelyn Fett