Mesopotamian Origins

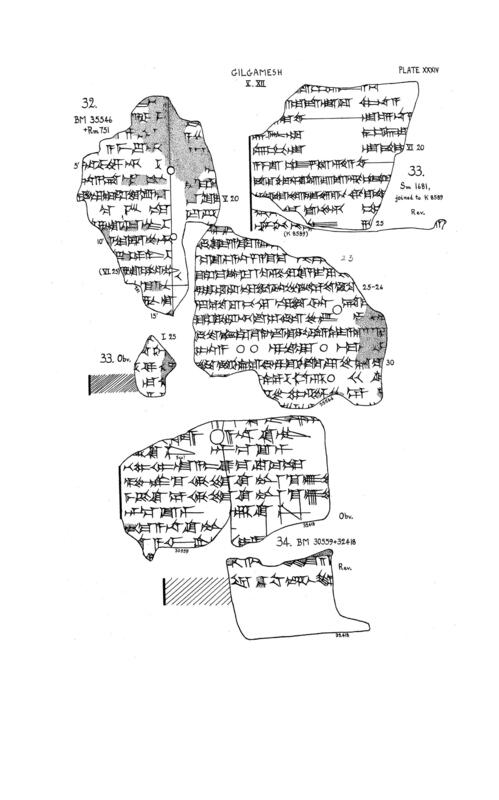

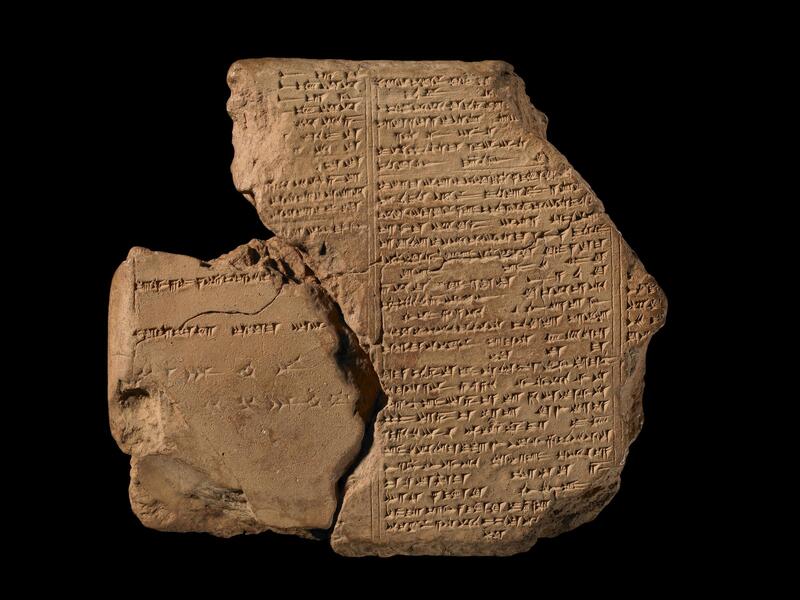

The earliest iterations of Lilith appear to come from the Sumerian class of sexual demons known as the Lilû (feminine form: Lilitu). In Tablet XII of the Epic of Gilgamesh and the story Gilgamesh and the Huluppu Tree (ca. 2000 BCE), Lilith appears as a "shrieking" vampiric demoness who destroys the Huluppu tree and flees to the desert after Gilgamesh slays the serpent-dragon:

A few centuries later, the Mesopotamian Lilith gained divine status–possibly inspired by the Canaanites who had always called her Baalat or “Divine Lady.” The clay tablet known as the Burney Relief or “The Queen of the Night” (pictured to the right) depicts this iteration of Lilith as she was believed to appear to the human eye:

Divine Inspirations

The well-known Lilith from Jewish folklore was most likely borrowed from these Mesopotamian characterizations. Before that, however, some scholars argue Lilith was adapted from the primordial Mesopotamian goddess Belili, while others claim her character resembles that of Ishtar or Lamashtu. The sexual and demonic aspects of Lilith’s later adaptations likely come from a combination of Ishtar, a renowned seductress as the Sumerian goddess of love, passion, and sexuality, and Lamashtu, a Sumerian mother goddess associated with kidnapping and consuming newborns.

The obsidian amulet pictured to the left was created to protect against the demoness Lamashtu, who is still referred to as “exalted lady” illustrating her divine status. Like the Burney Relief, the goddess is depicted with animal features (lion arms, for example) and adult animals at her feet.

Tablet VI of The Epic of Gilgamesh (pictured to the right) describes the scene in which Ishtar lusts after Gilgamesh and he rejects her marriage proposal. The hero is ultimately intimidated by Ishtar’s beauty and divinity, and is afraid of her because she is obsessive, prideful, and has inflicted horrible fates on past lovers that did her wrong.