Victorian Temptress

The best example of Victorian Lilith comes from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Lady Lilith” (1866). The painting once included the face of the artist’s mistress, Fanny Cornforth, but it was painted over at the commissioner’s request for sharper, colder, and darker features. The white, pink, and red flowers that adorn the background represent different kinds of love, communicating the complexity of female sensuality and sexuality–a perplexing notion in Victorian society. Fascinated with Lilith's threatening persona, Rossetti inscribed his original sonnet on the frame:

"Of Adam’s first wife, Lilith, it is told (The witch he loved before the gift of Eve)/ That, ere the snakes, her sweet tongue could deceive/ And her enchanted hair was the first gold. And still she sits, young while the earth is old, And, subtly of herself contemplative/ Draws men to watch the bright net she can weave/ Till heart and body and life are in its hold/ The rose and poppy are her flowers; for where Is he not found/ O Lilith, whom shed scent And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?/ Lo! as that youth’s eyes burned at thine, so went/ Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent/ And round his heart one strangling golden hair."

In 1867, Rossetti and his apprentice Henry Treffry Dunn replicated “Lady Lilith” using Cornforth as a model once more, indicating Rossetti’s view of Lilith as a representation of sexuality outside domesticity and matrimony. Lilith is also depicted combing her hair and holding a mirror to gaze at her reflection, overtly symbolizing her vanity and indifference to the male gaze (which makes her dangerous). Both versions of “Lady Lilith” exemplify the light brushstrokes, vivid imagery, sensual subjects and romanticized backgrounds that characterize many Pre-Raphaelite paintings. In both versions, the provocative depiction of Lilith with exposed shoulders and a loose-fitting dress is in direct contrast to the rigid criteria for female "purity" in the Victorian era.

The second “Lady Lilith” (watercolor this time as opposed to an oil on canvas) included an excerpt from Goethe’s Faust (1808), which was Lilith’s first appearance in modern literature. The excerpt comes from a dialogue between Faust and Mephisto regarding Lilith and her hair:

“Beware . . . for she excels all women in the magic of her locks, and when she twines them round a young man’s neck, she will not ever set him free again.”

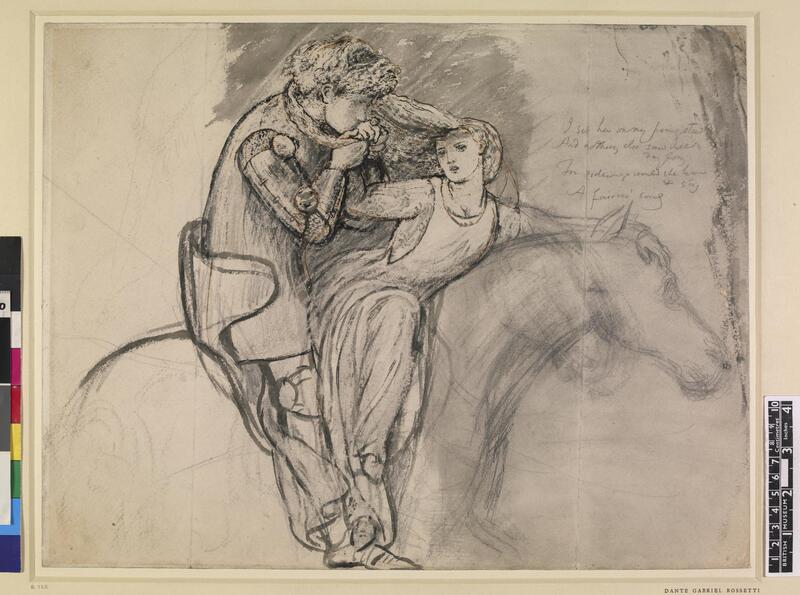

Similar to the imagery of Lilith’s hair in Faust, Rossetti’s “La Belle Dame sans Merci” (1855) features a Lilith-like woman strangling a man with her hair as he kisses her hand. This is the first time Rossetti played with this motif. La Belle Dame is cast as a femme-fatale; a cautionary tale for men that beauty threatens their control.

Lilith, Adam's First Wife, the woodcut on paper pictured to the right, depicts the scene from Faust referenced by Rossetti. Faust and Mephisto can be seen in the background, discussing Lilith, her flowing hair, and the wild boar next to her.