The Kent State Shooting

As tensions rose across university campuses, administrations and faculty members were struggling to keep control of the student protests. While most of the issues being protested had to do with the government, there was little the universities could do to please the students. Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, was filled with many New Left activists, especially regarding the Vietnam War. By 1970, the United States is still involved in the war in Vietnam, and America found itself further divided over civil rights and the war. However, Kent State was not considered to be a demonstrating school. The most the school had dealt with was cleaning and reorganizing after a “back-to-school bash” and that was only a matter of hours. Yet, by 1968, Kent State began to see subtle changes. A Students for a Democratic Society had formed on campus and on April 8, 1969, they attacked the university administration building in protest and abolishment of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program. Throughout that year more protests took place, with more and more demonstrators every day. Highway patrolmen and riot-trained deputies would appear on the scene and often arresting people who participated. However, this was just the beginning.

On Friday, May 1, 1970, Kent State students hear President Nixon’s announcement about the U.S. invasion of Cambodia as part of the Vietnam War. The students saw this move as coming from a repressive government and one that is in awe of its power and hold on the world. The reaction of the students was almost immediate. Going into town, students and other antiwar protestors spray-painted signs reading “POWER TO THE PEOPLE” and “GET OUT OF CAMBODIA”, while riots began to form. Policemen and citizens were injured, and students were arrested and taken to jail. Not sure pf how to control the riots, Mayor Satrom called in the National Guard. Guardsmen were mounted on campuses to keep the peace, but the commander of the National Guard, Major General Sylvester T. Del Corso, feared that the students would reach their breaking point.

On Sunday, May 3, 1970, prosecuting attorney, Ronald J. Kane, received news that the ROTC building at Kent State University had been burned down. The National Guard was given the order to move onto the university campus and there was serious talk about closing the school. However, the administration saw it unnecessary and the rest of the day appeared to be calm. When Monday, May 4, 1970, began everything seemed normal. Students rushed to their class and the guardsmen questioned when they would be going home. However, tensions shifted as the campus news broadcaster announced the noon rally that was scheduled. Just a few minutes before noon, almost fifteen hundred students had gathered and another two thousand to three thousand on the opposite side of campus. The antiwar chants echoed across and the guardsmen tried to keep it under control. The chanting increased:

“Off the pigs, off the pigs.”

“One-two-three-four, we don’t want your fucking war.”

“Two-four-six-eight, we don’t want your fascist state.”

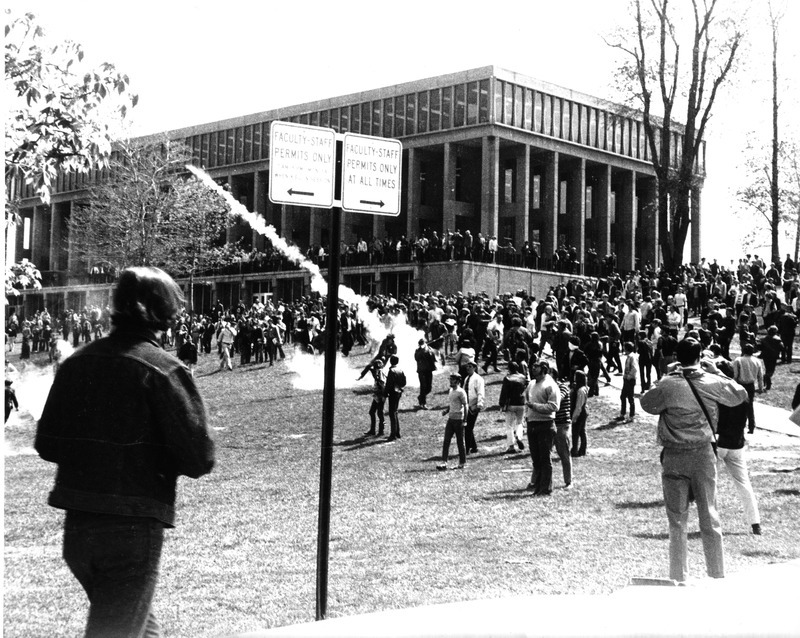

While chanting, the students began throwing rocks at the guardsmen and began walking towards them. They were almost 100 feet away from them when the order was given to launch the tear gas at the crowd of students. As the canisters hit the ground, many students attempted to throw them back at the guards. However, as the guardsmen walked towards the crowd, many students panicked and ran. As others continued to throw rocks, a shot rang out. Then many others followed after.

The result of the shooting at Kent State University, on May 4, 1970, was the death of four students: Allison Krause, Sandy Scheuer, William Schroeder, and Jeff Miller. Krause and Miller had participated in the protest, while Scheuer and Schroeder were simply walking by. The death of these students shocked the nation and caused outrage across other universities and colleges. In response to the Kent State shooting and the Jackson State shooting just 11 days later, students continued their protests, riots, and demonstrations, forcing the U.S. government to acknowledge the outcry of its people and the division that the Vietnam War was causing.